A Union in Crisis

May 24, 2021 | Expert Insights

Amidst intense speculations about a possible disintegration of the United Kingdom, crucial elections have been held to the regional assemblies in Scotland and Wales, along with local and mid-term polls in England. Pro-independence parties are projecting the results as a popular call for separation.

While the Tories have made strident gains in England, celebrations were muted owing to the results pouring in from Scotland. Securing a historic fourth term in office, Nicola Sturgeon, and her pro-independence Scottish National Party (SNP) have won a convincing 64 of the 129 seats in the Edinburgh-based Parliament, finishing just one seat short of an overall majority. She is expected to make up for this deficit through an alliance with the Scottish Green Party (The Greens), which controls eight seats. Together, they will be able to exert renewed pressure on Westminster to authorise a second referendum on the secession of Scotland.

Meanwhile, in Wales, the victory of the vehemently pro-devolution Labour party portends a mounting constitutional crisis for the Union. A visibly nervous Boris Johnson has invited the leaders of the UK's devolved regions to a summit, hoping to counter a potential break-up. It remains to be seen whether the Conservatives’ brand of ‘muscular unionism’ prevails in this deeply divided country.

DEVOLUTION OF POWERS

Towards the end of the 20th century, the devolution of powers to Cardiff, Edinburgh and Belfast had radically changed the course of British politics. Although it did not equate to federalism, the devolved regions had been granted a greater level of self-autonomy, with the ultimate authority residing at Whitehall. Any disputes between the different layers of government were papered over by deferring to the powers of the European Union.

Over the years, however, Westminster was accused of a policy of ‘devolve and forget’. Many emerging factions within Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales suspected it of centralising power under the garb of parliamentary sovereignty.

A significant turning point came in 2016 when Britain sought to assert greater control over its internal markets by quitting the EU. With the passing of the Brexit referendum, the Union was radically polarised, with electors in Scotland and Northern Ireland preferring to remain in the EU, even as a majority in Wales and England voted to leave the bloc.

Now, as the region simmers from economic uncertainty and political rancour in the wake of Brexit, these fault lines have been thrown into sharp relief.

SEVERING THE CORD

The independence movement in Scotland has always had some traction since the 1970s, owing to the rise of the SNP. Apart from issues pertaining to the devolution of power, London’s control over the revenue from North Sea oil had been a politically contentious issue in the region. Nonetheless, when a referendum on independence was held in 2014, around 55 per cent of the Scottish public had voted against it. Analysts believe that a principal reason was the desire to stick with the UK’s long-standing membership of the EU.

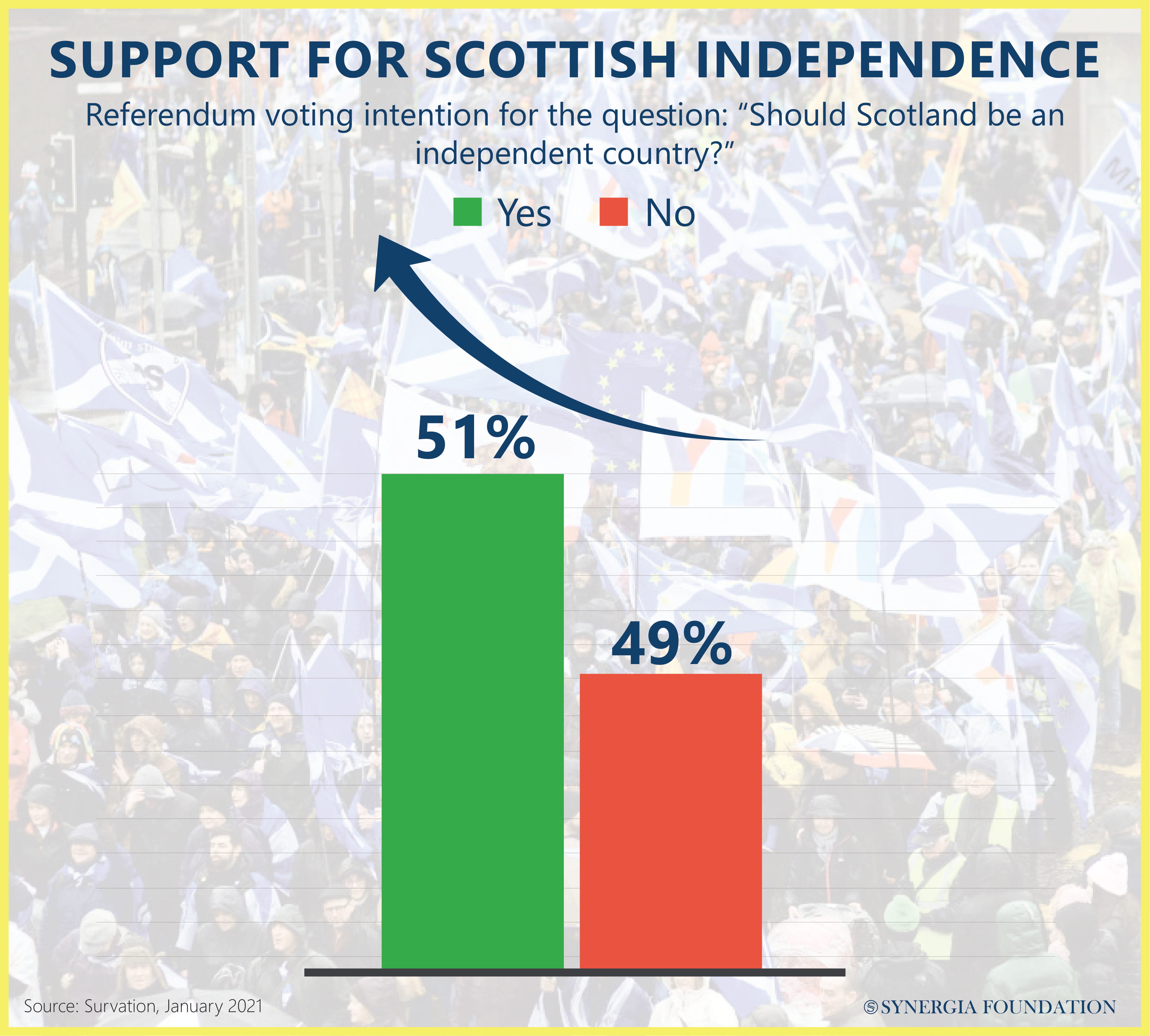

After the 2016 vote on Brexit, however, this strategic calculus changed, with many Scots feeling betrayed by the decision to leave the EU. The conclusion of a bare-bones trade deal with the bloc did little to assuage their concerns about economic disruption, as important sectors like the Scottish fish industry suffered massive declines in their exports.

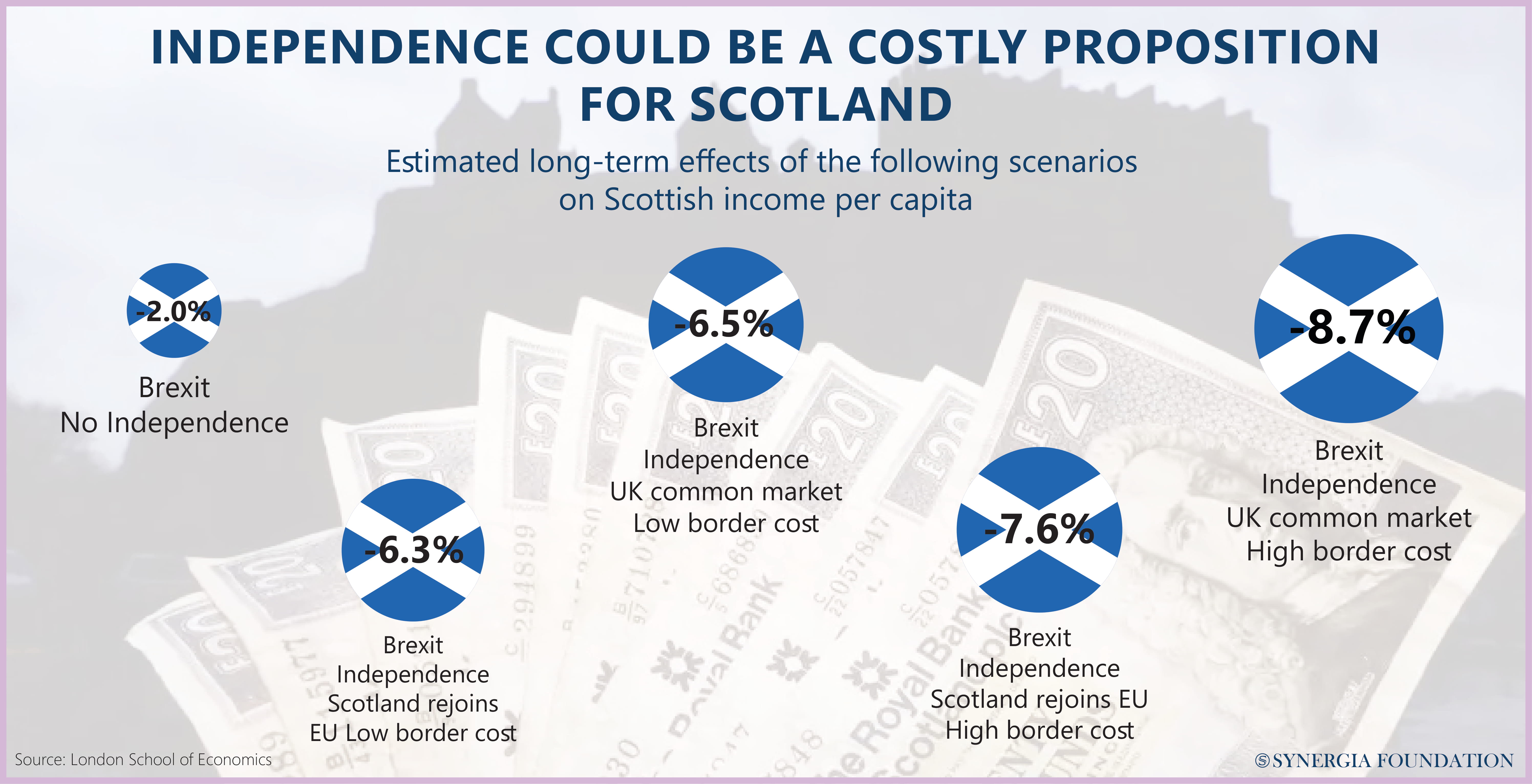

Capitalising on this sentiment, members of the SNP have steadily pushed for a plebiscite on independence. According to them, Brexit has triggered a 'material change in circumstances’, which justifies another vote on Scottish secession. In recent times, they have also sought to distinguish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon's 'deft handling’ of the Covid-19 crisis from Boris Johnson’s alleged mismanagement of the pandemic during its initial stages. This strategy seems to have paid off, with public opinion polls suggesting that the number of Scots who support independence have gone up over the last two years.

However, it will not be easy for the SNP to conduct another referendum, despite coming to power. Prime Minister Boris Johnson has categorically stated that he will block any such vote. Even though the Scottish Parliament has its own portfolio of devolved powers, it is the Westminster that ultimately controls legislation pertaining to constitutional matters. Under Section 30 of the 1998 Scotland Act, only the UK Prime Minister can authorise the holding of a referendum before Holyrood passes a law to that effect.

Since London is likely to stonewall any such attempts, the SNP may be forced to pass a plebiscite bill in the Edinburgh parliament that is devoid of official sanction, paving the way for a ‘wildcat’ independence referendum. However, this will inevitably spur a feverish legal battle at the UK Supreme Court, further aggravating the Anglo-Scottish standoff.

RETURN TO THE TROUBLES?

The results of the Scottish elections have been keenly watched in Belfast, which is facing its own spate of troubles in the aftermath of Brexit. Unhappy about the Northern Ireland Protocol that effectively creates a trade border with England, Scotland and Wales, many Unionists in the region have been left disillusioned. Sporadic violence has broken out across the province, raising the spectre of renewed ‘Irish Troubles’. Arlene Foster, the Unionist leader of the government in Belfast, has announced that she will step down at the end of May 2021, blaming the Brexit deal for having destabilised the region.

Meanwhile, public discussions about a referendum on Irish unity have increased, with opinion polls showing that a majority of the Northern Irish favour a vote on reunification with the Republic of Ireland. Against this backdrop, the victory of the SNP in Scotland has been heralded as a game-changer for the constitutional future of the Union Jack.

Sinn Fein, a prominent Republican party, has already indicated that a border poll may take place as early as 2030. Under the terms of the Good Friday Agreement, which ended three decades of violence between Catholic nationalists and Protestant unionists, a referendum can be called if a ‘yes’ majority looks likely. The first indicator for any such mover will be the Northern Ireland parliamentary elections next year, where a Sinn Gein victory may accelerate calls for a broader break-up.

Assessment

- The SNP must carefully consider the economic costs of separation and the viability of an independent Scotland over the days to come. Applying for EU membership as a separate nation can create a hard border with England, causing several disruptions and hindering trade. Learning from the Catalan example, where an unconstitutional pro-independence referendum in 2017 had failed to translate into separation from Spain, the SNP will need to ensure that its stand-alone referendum does not flounder on legal grounds.

- The negative impact of Brexit has invariably spurred a great deal of soul-searching on the constitutional future of Northern Ireland. Given that the province remains a political tinder box largely divided along religious and nationalist lines, Stormont will not find it easy to reconcile the competing visions of sovereignty.

- Even in Wales, a desire for separation simmers under the surface. As can be recalled, Plaid Cymru, a Welsh nationalist party had pledged to hold a referendum on independence if voted to power. However, it has only managed to secure the third place in the recently concluded elections, providing a temporary breather to those who oppose the disintegration of the United Kingdom.

Comments