Uncharted Territories

January 21, 2022 | Expert Insights

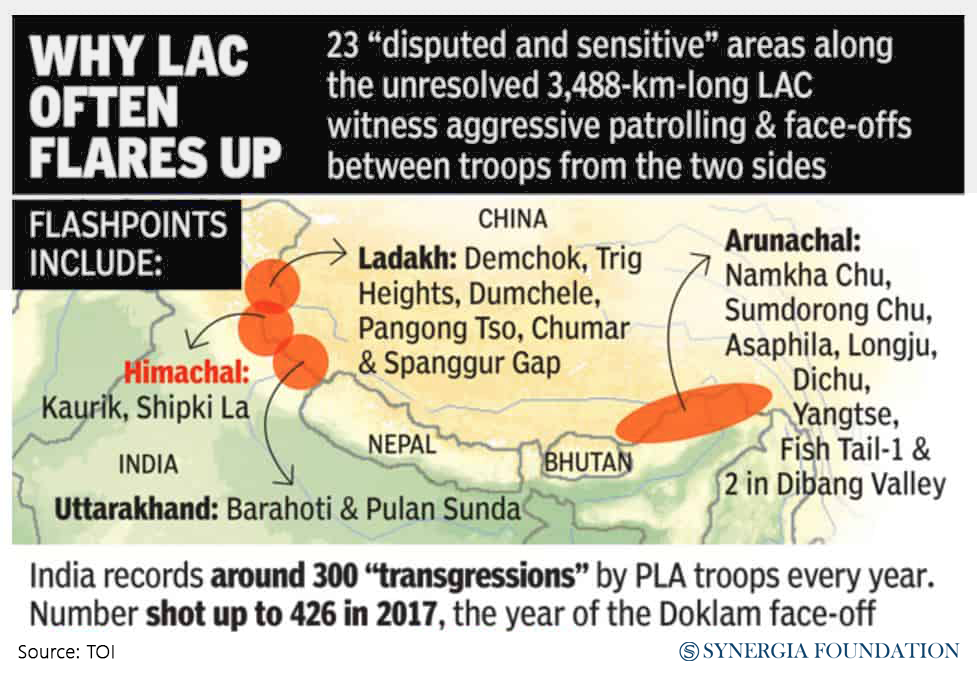

In yet another move for territorial consolidation, Beijing has ‘standardised’ its official Chinese names for fifteen places in the disputed Eastern Indo-Sino border area. Making unilateral claims upon border areas is a strategy pursued by China, not only in its land borders, but also in its maritime borders in the South and East China Sea. However, the recent formalisation of names gains significance, in light of the deteriorating security and military relations between the two Asian giants.

Background

A history of instability at the borders, coupled with a long process of de-escalation despite ongoing talks, is indicative of a diplomatic deadlock when it comes to territorial integrity and sovereignty. As can be recalled, the border disputes date back to the colonial era. The McMahon Line drawn in 1914 to demarcate the territories between the two countries is not considered valid by the Chinese.

Apart from that, the ill-defined borders are largely attributable to the rough geographical terrain which hampered the conduction of land surveys by the British. The high mountains and huge expanse of river/marsh boundary has also made an accurate demarcation difficult, leading to unverified and unilateral claims by China.

The unsettled border disputes serve as a constant irritant in Indo-Sino relations. Since May 2020, all three sectors of the border area have witnessed military build-ups and stand-offs. The latest point of friction is the Arunachal border, with China issuing official names for fifteen disputed areas.

Analysis

The new Land Border Law passed by China came into effect on the 1st of January 2022. The law is a tactical effort at encouraging citizens and civilian organizations to assist the People’s Liberation Army. It constitutes an attempt to engage the locals in the aggressive Chinese territorial security framework called ‘mass defence’, which includes information collection, order maintenance, sovereignty and territorial defence.

The timing of this law is indicative of its relation to the Indo-China war. The law is especially relevant for the eastern sector, considering that the border area runs through a fully inhabited plains, occupied by specific tribes and indigenous people who are often caught in the web of geopolitics. Garnering popular support and mandating cooperation may also assist the Chinese troops in a spiritually and religiously fragile region (Arunachal).

Beijing’s priority regarding the ‘governance of the frontier’ with the help of Chinese settlers is evident from its chain of Xiaokang border defence villages along the LAC. It will not only create a buffer but also provide a standing back-up to the border posts manned by the Chinese military. The new map of China shows the entirety of Arunachal Pradesh, the Barahoti Plains in Uttarakhand and areas up to the 1959 Claim Line in Ladakh as part of its territory.

China’s border disputes are not restricted to its boundaries with India. The continuous border disturbances around the Dragon depict how its defensive nationalism has morphed into aggressive nationalism. While some scholars argue that it stems from its territorial insecurities, one cannot ignore the ‘strongman’ trend in domestic politics which calls for ‘absolute control’ and preaches ‘sacred and inviolable sovereignty and territorial integrity’.

Counterpoint

The sudden Chinese aggression can be interpreted as a reaction to some of the political decisions taken in India. The move to make Ladakh a Union Territory has not gone down well with the Chinese administration, considering that several areas in Ladakh are still disputed.

Initially, the Chinese troop build-up along the LAC at Galwan valley and Depsang plains had come as a response to the construction of the Dabruk-Shyok-Daulat-Beg-Oldie road. The road, 10 kms from the LAC connects Leh to India’s highest air-strip at the base of Karakoram range, and runs very close to the Chinese-controlled Aksai Chin. The strategic significance of this road had made it easier for the Indian troops to man their borders, reducing the historical tactical advantage wielded by the Dragon in the Western border sector.

Another aspect that triggers the escalation of unsettled Indo-Sino border disputes is India’s policy tilt towards America. This explains China’s strengthening of its defence capabilities, hailed as the ‘anti-access capability’ by scholars like Aron Friedman. According to this theory, Beijing intends to acquire capability that denies Washington the ability to rescue its allies in the face of Chinese aggression. Currently China considers India one of US’s largest pawns in its Asian foreign policy and the theory justifies itself as the military disturbances perpetuate despite high-level military and executive engagements.

Assessment

- In 2020, during the border scuffle, the Indo-China bilateral trade had hit a record high of 100 billion USD. It is, therefore, evident that Beijing has strictly compartmentalised its engagement with the South Asian giant. Security/defence problems have not reflected negatively upon economic and trade engagements. This is in stark contrast to Indo-Pak military scuffles, which often witness a complete closure of cross-border trade and a significant decline in bilateral economic exchange.

- China has often voiced its intent to return bilateral relations to economic and diplomatic cooperation, despite the ongoing border clashes. Hence, the border incursion seems to be nothing more than muscle flexing by Beijing to re-enforce its military might in India’s backyard. However, history teaches us that the Dragon in the neighbourhood cannot be trusted and the only way forward is with utmost caution and vigilance. Even as we continue to engage economically, the relevance of back-channel diplomacy must not be under-estimated.

Comments