Standing Trial

May 18, 2021 | Expert Insights

At the 46th session of the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) in Geneva, which is currently ongoing, Sri Lanka faces a public probe into its post-war reconciliation measures. This follows a highly controversial report by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, that had delivered a scathing indictment of accountability and truth-seeking mechanisms in the island-nation.

In the run-up to this trial by fire, Colombo has officially sought New Delhi’s help. President Gotabaya Rajapaksa has written to Prime Minister Narendra Modi, expressing the hope that India would support its neighbour in defeating the resolution that challenges Sri Lanka’s human rights record. In addition, the Media and Information Minister Keheliya Rambukwella, as well as Foreign Secretary Jayanath Colombage, have followed this up through unofficial channels.

This resolution comes at an inopportune time for Sri Lanka. Only recently, the country had made headline news by reneging on a 2019 tripartite agreement with India and Japan, that provided for the joint development of the East Container Terminal (ECT) at the Colombo Port. While opposition from domestic port workers’ unions had been ostensibly cited as the reason, strategic analysts in New Delhi were suspicious of a possible Chinese hand.

In a bid to undo this damage, Colombo has now awarded a contract to Adani Ports for developing the West Container terminal, making it the first Indian port company to operate in the island-nation. It remains to be seen whether the grant of this alternate project will be sufficient to prevent a visibly miffed Indian administration from flexing its muscles against Sri Lanka, at the approaching vote in the UNHRC.

A HISTORY OF UNHRC RESOLUTIONS

Over the last twelve years, Sri Lanka has faced at least seven resolutions on the question of human rights. New Delhi has been an active participant in these discussions, choosing to constructively engage with its ‘close friend’ across the Palk Straits.

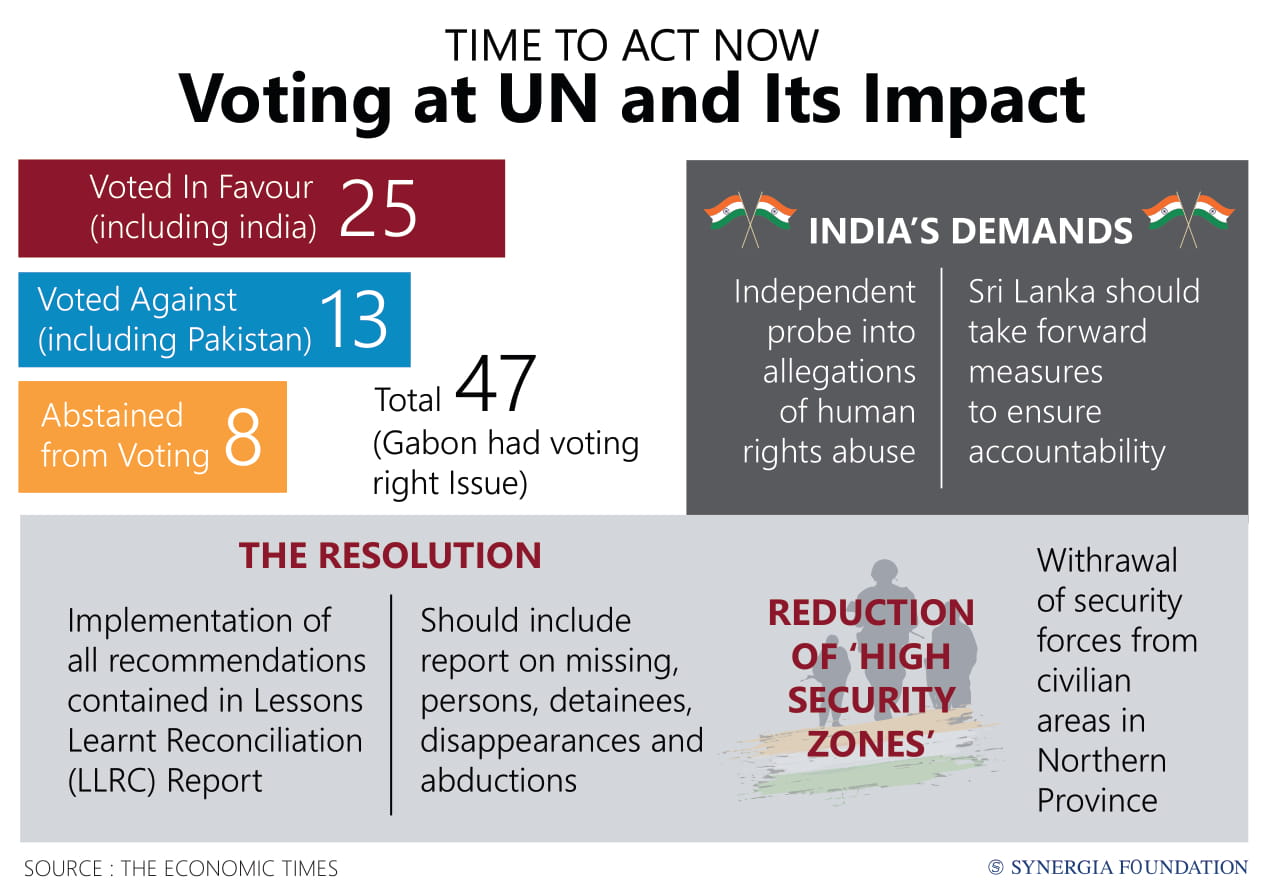

However, in 2012, the US had brought in a substantial resolution (19/2) against Sri Lanka, which was approved by India for the first time. A year later, New Delhi also voted in favour of another resolution (22/1) against its neighbour. At the time, domestic Indian politics had played no small part in this decision. As can be recalled, Tamil Nadu’s main opposition party, Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), had withdrawn from the ruling coalition at the Centre, alleging that India was not doing enough for the Sri Lankan Tamils.

Easing bilateral friction to a certain extent, India had abstained from the following Resolution (25/1) in 2014. According to it, it was important to acknowledge some of the key reconciliation measures that the Sri Lankan government had undertaken during the course of the year.

Fortunately for New Delhi, it was spared its annual dilemma in 2015, as Colombo voluntarily undertook to co-sponsor UNHRC Resolution 30/1. This was triggered by the defeat of Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapaksa in the Presidential elections, along with the subsequent loss of his political party at the country’s Parliamentary polls. The victorious Maithripala Sirisena-Ranil Wickremesinghe government, which came to power on the promise of speeding up the ethnic reconciliation process, had agreed to partner the 2015 resolution.

This, however, proved to be extremely polarizing in the country, as it called for a domestic accountability mechanism, with the prospect of appointing international judges. During his Presidential campaign in 2019, Mr. Gotabaya Rajapaksa went on to make this an electoral plank by stating that his regime would never put military officers on trial. Upon sweeping the polls later, his government unilaterally pulled out of this Resolution.

Now, with the freshly drafted 2021 resolution, the new Rajapaksa government will have to face its first-ever test at the UNHRC.

IN THE DOCK

The draft resolution has been submitted by a ‘Core Group’, consisting of the United Kingdom, Canada, Germany, Malawi, Montenegro and North Macedonia. It effectively responds to a condemnatory report by the UN High Commissioner of Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, that accuses Sri Lanka of proactively obstructing investigations into past crimes. It also highlights the accelerating militarisation of civilian governmental functions, deployment of anti-terrorism laws, the reversal of important constitutional safeguards, intimidation of civil society, as well as exclusionary rhetoric to bolster this claim. As a punitive measure, the report has additionally called for targeted sanctions and International Criminal Court procedure against those responsible for rights violations.

Acknowledging the same, the newly drafted resolution urges the UNHRC to devise strategies that support “accountability processes” and “relevant judicial proceedings”. It also advocates for the implementation of Resolution 30/1.

GEOPOLITICAL FISSURES

Sri Lanka has termed the persistent efforts of the UN and its human rights body as a “purely political move” and “unwanted interference by powerful countries." It has, in turn, lobbied with member states, especially those with which it enjoys close relations, in order to support its stand.

This is causing fault lines in its foreign relations to emerge along expected lines, with China and Pakistan defending Sri Lanka, while the EU and UK are demanding enhanced accountability.

In an apparent endorsement of human rights, the US has also supported this resolution. Underlying its decision, however, is the growing displeasure over Sri Lanka’s ‘cosying’ up to China, which is perhaps incentivised by larger investments coming in from Beijing. Washington is keen to offset the latter’s expanding economic footprint in South Asia through the Belt and Road Initiative, which it believes is a cover for geopolitical influence. However, much to its chagrin, Sri Lanka has rejected bilateral avenues for cooperation like the $480 million U.S. grant, that seeks to facilitate transport development and land registration under the Millennium Challenge Corporation Compact.

In this fractious environment, India can make a difference in the upcoming vote at the UNHRC. Well aware of this, Sri Lanka has called on its neighbour to exert significant diplomatic heft in opposing the draft resolution. In a conciliatory move, the island-nation has also cleared the joint development of the West Container Terminal with India and Japan, as an alternative to the ECT. However, stung by a series of affronts in the recent past, the Indian side has refused to reveal its cards, as yet.

Assessment

- New Delhi has not outrightly dismissed the report prepared by the UN High Commissioner, an outcome that Sri Lanka would have desired. Naturally, this is triggering speculations about a possible 'cold shoulder' to Colombo in the upcoming Resolution at the UNHRC.

- For India, a collapse of the ECT venture is not the only factor that figures in its strategic calculus. It is actively seeking to constrain Beijing's presence in the island-nation by pushing back against Chinese projects in areas like the Jaffna Peninsula, which is merely 50 km off Tamil Nadu’s coast.

- In India, the Sri Lankan Tamil issue will always be a talking point in Tamil Nadu politics. Owing to the upcoming Assembly polls, political parties are looking to capitalize on any issue that swings votes in their favour. In this regard, renewed emphasis may be placed on the implementation of the 13th Constitutional amendment in Sri Lanka, which stems from the 1987 Indo-Sri Lankan accord and aims to devolve power to the Tamil provinces.

Comments