Srilanka: Economy in Doldrums

September 17, 2021 | Expert Insights

Amidst escalating food prices, looming debt repayments and dwindling forex reserves, the Sri Lankan government has declared an economic emergency on 31 August 2021. The military has been called in to manage the simmering crisis by rationing supply and penalising the hoarding of essential goods.

Background

Sri Lanka is a developing economy, where the growth is primarily driven by agriculture, services, and the light industry sectors. The country is, by and large, committed to a free-market ideology, boasting one of the most liberal foreign trade regimes in the world. Apart from being a major exporter of garments, coconuts, tea and rubber, it imports consumables, petroleum, machinery, and other manufactured goods.

This is in sharp contrast to the South Asian nation’s earlier years under colonial rule, where plantation agriculture had been the major source of revenue. Manufacturing activity had been negligible, while banking and commerce were perceived as allied activities to support agriculture.

Following its Independence in 1948, Sri Lanka adopted a liberal trade and foreign direct investment (FDI) regime. Owing to an improved balance-of-payments situation, the country was able to do away with most of the import restrictions imposed by the British government. Post the 1950s, however, it veered towards an import substitution policy in both manufacturing and foodstuffs, eventually emerging as one of most inward-oriented economies in the world, outside the Communist Bloc.

After years of protectionism, wherein the annual average growth rate of the country had shown signs of decline, Sri Lanka finally embarked on economic liberalisation in 1977. It sought to stimulate private investment and increase the country's foreign earnings by promoting exports. Although these policies met with limited success, in the beginning, the escalation of the internecine ethnic conflict in the 1980s had undercut the benefits that were hitherto derived.

Analysis

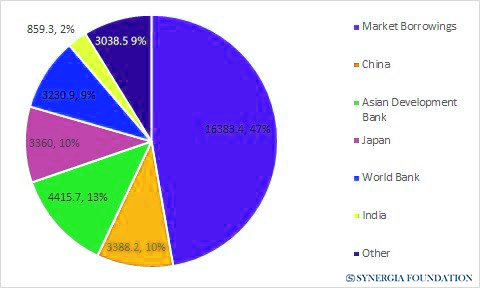

Currently, Sri Lanka has a highly diversified economy, with rapidly growing manufacturing and service sectors. Even the agricultural domain has been modernised, allowing it to achieve near self-sufficiency in rice production. Although international trade is a critical part of the island economy, it has been witnessing a sharp rise in foreign debt since 2014. Economists around the world have expressed grave concerns about the country’s debt sustainability, something that has been aggravated by the onset of the COVID-induced global recession.

While the pandemic may have exacerbated the situation, experts believe that a number of structural factors have contributed to the current economic crisis in Sri Lanka. For one, the country has failed to attract enough foreign direct investment (FDI) to meet its rising debt obligations in the post-conflict era. Secondly, tourism - a major source of foreign currency, has been hit ever since the deadly Easter Sunday bombings of 2019, with COVID-19 lockdowns having amplified the distress. Given that tourism accounts for more than 10 per cent of Sri Lanka’s GDP, the colossal impact of this dip on forex reserves cannot be underestimated.

Moreover, the island country has recently registered an outflow of $1 billion, which was used to pay off its international debts. As a result, the forex reserves dropped to a dismal level of $2.8 billion in July 2021, with an import cover of only 1.8 months. This raised valid concerns about the nation’s ability to repay another $3.65 billion in hard currency borrowings, which are due next year.

As their coffers dry up, the Sri Lankans are forced to shell out more money to purchase the foreign exchange required for importing goods. Naturally, this has resulted in a depreciation of the Sri Lankan rupee, which has fallen by around 8 per cent against the U.S. dollar. To make matters, the balance of payments crisis has translated into rising food prices.

Given that the island depends heavily on imports to meet its basic food supplies, the fact that it is running out of foreign exchange to finance these purchases is not a good sign. Additionally, the Sri Lankan government has ill-timed its transition to organic agricultural production by banning chemical fertilisers. It is no surprise, therefore, that a state of emergency has been declared in relation to food shortages. Authorities have been empowered to seize food supplies from hoarders and contain inflation by supplying them to consumers at fair prices.

Counter-point

While emergency regulations penalising food hoarding may be warranted in times of crises, the strong-arm tactics employed by the army can be a slippery slope. Any attempt to stem recession by expanding the role of the military in civilian functions should be subject to constitutional safeguards. As cautioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet, the current social, economic, and governance challenges faced by Sri Lanka should not operate as a pretext to impinge on fundamental rights, civic space and democratic institutions. Even in emergency situations, institutions like the military should be subject to some degree of accountability.

Assessment

- Over the coming days, it remains to be seen if Sri Lanka will consider a bailout plan by the International Monetary Fund. If it does, the country will have to subject itself to serious austerity measures, which may be painful in the immediate to short term.

- To save political face, the incumbent Rajapaksa administration might delay its outreach to the IMF by approaching China for help. Indeed, the current economic crisis is likely to push the regime into aligning more of its policies with Beijing’s interests. This does not augur well for India, which has been attempting to counter the Dragon’s footprint in its immediate neighbourhood.

Comments