SPYWARE: PLAYING WITH FIRE

November 12, 2022 | Expert Insights

Undoubtedly, digitalisation has quickened the pace of our lives and made it more accessible. But it comes with its dark side as digital surveillance has increased worldwide, striking down individuals' right to privacy and threatening democratic norms.

Recently, the media has been flooded with allegations of spyware being deployed to target opposition leaders, journalists, lawyers and activists in France, Spain, Hungary, Poland, Greece, India and even within the European Commission, the EU’s cabinet-style government. Apparently, the software is so designed as to infiltrate surreptitiously into an electronic device (primarily smartphones) and transfer private information to third-party sources. Once in possession of any 'incriminating information,' the state can single out and use other state organs to prosecute the individual. This mode is becoming the most favoured means of crushing dissent, and even liberal democracies are not entirely immune from its temptation.

Background

Sovereigns have been carrying out physical domestic surveillance for centuries- for law enforcement, counter-terrorism, political purposes, and to root out potential rivals. Mass surveillance through electronic systems such as spyware has streamlined and intensified the entire process, widening the depth, breadth, sources, and variety of the information available to governments. Even worse, the amount of data that electronic surveillance can generate can never be matched in quality or quantity by more traditional means.

As early as 2010, according to a study by the National Cyber-Security Alliance, an American non-profit organisation, 61 per cent of surveyed users' computers were infected with some spyware, with 92 per cent having no knowledge of it. In 2013, Edward Snowden, now sheltering in Russia after having been granted Russian citizenship this September by President Putin, spilled the beans on the spyware used by the U.S. National Security Agency against private citizens in the U.S. and abroad. This raised serious questions about the practice of cyber surveillance by world governments to push their political agendas.

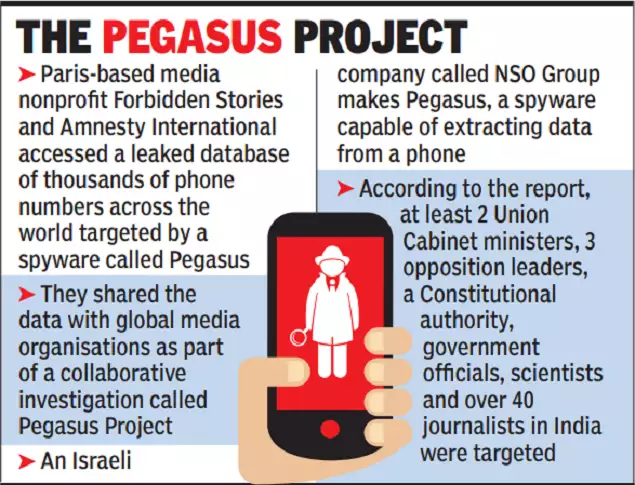

Modern smartphones and applications are becoming increasingly complex with built-in encryption, which most government agencies lack the expertise to crack open using their in-house facilities. This opens a vast market for shadowy private companies who create software to bypass the security of electronic devices' mass usage; Israel's NSO group and the Italian Tykelab are the most notorious but not the only ones. It is a well-documented fact that NSO spyware (the Pegasus being the most famous) and that of Tykelab are being widely used in Libya, Pakistan, Malaysia, Portugal and even Greece, which was, till recently, touted as the most cyber-safe country in the world.

Analysis

Carnegie's AI Global Surveillance (AIGS) Index shows that 75 of 176 countries actively use AI technologies for surveillance purposes, with China and the U.S. topping the list. Huawei alone provides AI surveillance technology to at least 50 countries. Nowhere is the power of state-sponsored mass electronic surveillance more evident than in China, where 13 million Turkic Muslims/ Uyghurs of Xinjiang are under constant state watch through mobile apps, software and biometric data collection.

Electronic surveillance using spyware and other forms of AI is blurring the boundaries between a surveillance state and a welfare state. The adoption of digital currency and smart cities, not only by China but also by established democracies, while providing citizens with expeditious and seamless public services, can enable the state to inspect and control people’s financial transactions, as well as predict and pinpoint political street protests. The state thus becomes an omnipresent and omniscient entity dominating every aspect of the citizen's life, collecting data on their personal beliefs, interests, and activities on the pretext of national security. The growing nexus between the state and private spyware corporations greatly enhances the government's ability to get around the security shield of private devices and spy on common citizens and dissidents alike.

Apart from the Predator spyware scandal in Greece in 2022, every other software used to spy targeted people in EU countries could be traced back to the notorious NSO group, best known for its Pegasus spyware. Pegasus's claim to fame was its unique zero-click exploits capable of insidiously tampering with data from the microphone, camera, internet, etc., of the target's phone. The publicity led to a worldwide crackdown on the NSO group, with lawsuits slapped on it by Apple and the U.S. black listing it.

This has opened the field for an ever-increasing number of other aspirants, such as the Australia-based DSIRF, North Macedonia-based Cytrox, etc., all jostling to fill the vacuum. They are reported to have already inked deals with Hungary, Syria and Bangladesh for mass and directed surveillance by hacking the targets' electronic devices.

Without robust transnational laws curbing such activities, the electronic surveillance business is apparently thriving. While many democratic nations have promulgated digital security and data privacy laws, enough loopholes remain, especially when the state is the perpetrator.

Assessment

- To safeguard the rights of individuals, there is a requirement to adopt multilateral cyber surveillance treaties and frameworks to ensure that all software or hardware products available for distribution or use by national governments comply with essential privacy requirements.

- A balance between national security, individual privacy, and civil and political rights must be established, with the judiciary taking on the role of a watchdog, duly reinforced with comprehensive regulations. All stakeholders, including the public, must be incorporated when such regulations are being framed.

Comments