SOVEREIGN DEBT DEFAULT

November 5, 2022 | Expert Insights

Background

Sovereign debts can be viewed as an oxymoron because of the antithetical pairing: sovereign status of the bond issuer government and the debt obligation it consequently incurs. They are also paradoxical in terms of risk assessment- evidently, sovereign countries have more creditworthiness than individuals; on the other hand, if they default, limited recourse to compensation is available to the investors other than seizing the defaulter's overseas assets.

A sustainable sovereign debt is linked to the inflow of foreign investment and foreign exchange that boosts domestic growth, development and economic health, while defaulting and debt distress is a painful process which threatens macroeconomic stability, setting back a country's development for years. However, the sovereign debt crisis is not new; it dates back to the mid-twentieth century when several nation-states and modern economic institutions and relationships were established.

Cases in point are the sovereign debt default by nations such as Russia in 1998 and Argentina in 2001 because of reasons that stretched back for decades. After the USSR had split into separate countries, Russia assisted its former constituent republics by importing heavily from them, thus using up its foreign saving. The command structure of the Russian economy and the economic cost of the first Chechnya war were other reasons. On similar lines, Argentina's sovereign debt default was the culmination of three consecutive years of economic recession resulting from a long military dictatorship, unfinished projects starting with foreign investment, higher defence spending and the Falkland War. More recent is when the 2008 US financial crisis, coupled with acts of internal economic imprudence like paying high wages with an under-competitive economy, corrupt state-run businesses, reckless borrowing and floundering tourism industry caused the Eurozone nations of PIGS (Portugal, Italy, Greece and Spain) to default on their debts.

Analysis

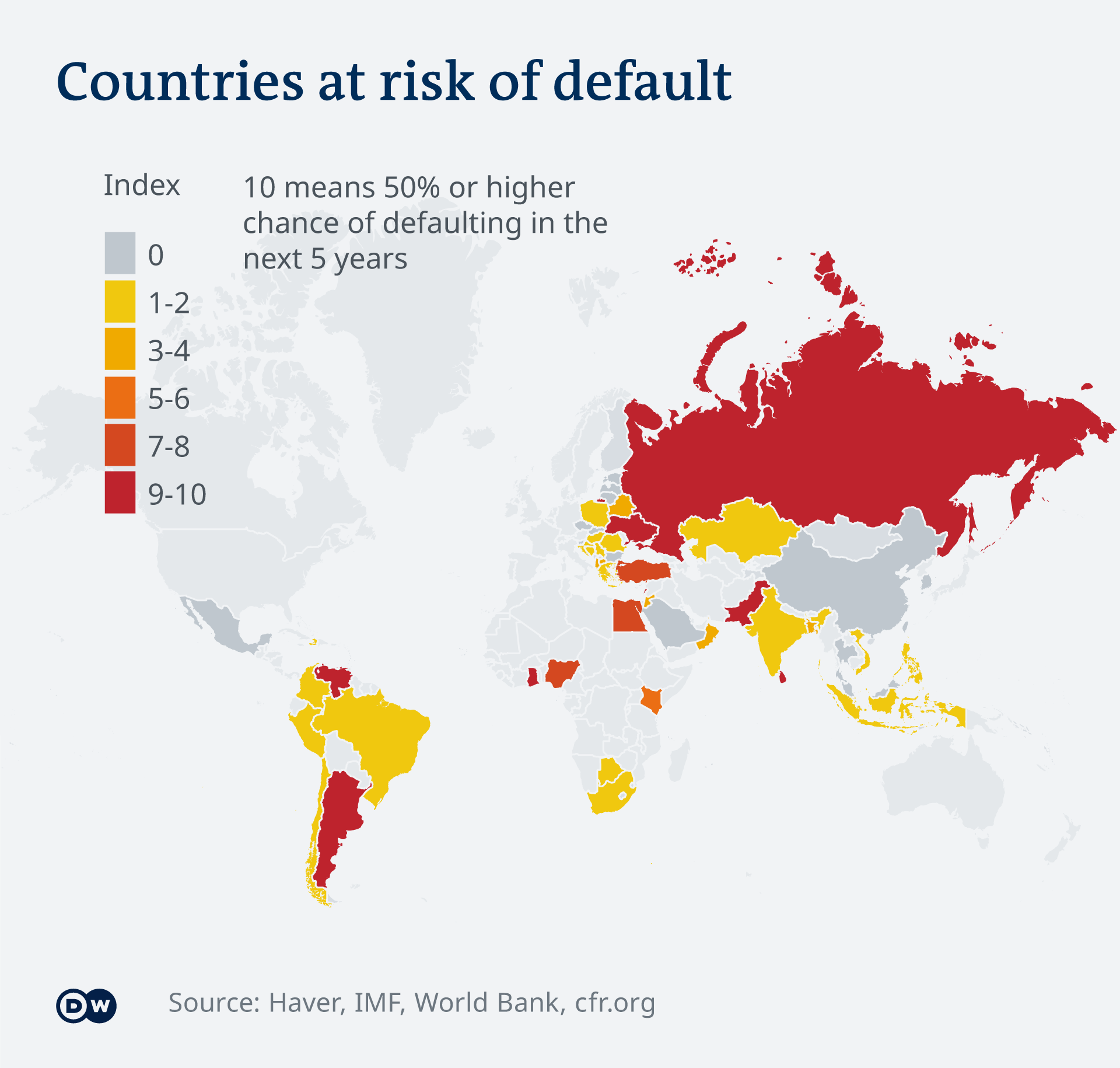

Historically, as seen above, factors leading to sovereign defaults have been highly varied, resulting in difficulty in accurately predicting the crisis's time or whether a country's economic downturn will result in such a debt default. Moreover, since external borrowing by the government has only recently become a norm, sovereign debt defaults on loans financed by foreign currency were rare. Hence many economic experts of yesteryears have termed a sovereign debt default as a ‘Black Swan’ event.

India's external debt as a percentage of GDP has declined consistently from around 40 per cent of GDP in the 1990s to almost 20 per cent since the 2000s and has not spiralled since the 1991 economic reforms. Recently, the Indian rupee has depreciated, troubling macroeconomic stability, including external debt. India is experiencing high inflation and large twin deficits. In response, the RBI's increase of policy rates will eventually slow growth, making a higher ratio of external debt to GDP possible in future.

Implications of a sovereign debt default in India, as elsewhere, depends on the country's economic state, the value of its currency, banking system, stock market, corporate borrowing, EBCs, nature of the creditors, the gravity of external debt, and so on.

However, in all cases, the default leads to a loss of reputation, making it harder for the government to attract foreign investment in the future because of the higher interest rates due to its reduced credibility. Intricately linked Indian and global markets might result in the slow growth of especially the Asian economy. Withdrawal of investments by foreign portfolio investors as well as India terminating development contracts abroad, hyperinflation, unemployment, plummeting exchange rates in the international market, national banks' lending at higher interest rates, thereby stalling growth and exports, people withdrawing all their money from banks, and reduced living standards are other fallouts.

Hence measures that protect investment and (foreign) investors' interests, such as investment protection treaties (also called Bilateral Investments Protection and Promotion Agreements (BIPA) or Investments Protection and Promotion Agreements (IPPA)) and Investor Compensation Funds, such as the one created by SEBI, are imperative. This results in the destination country attracting more foreign investment and foreign exchange, consequently generating more growth potential.

This indicates some advantages for India if it affiliates with the ICSID Convention. Adopting a stable, mutually acceptable structure of dispute conciliation would guarantee enhanced protection and rights to Indian investors and their foreign investments and dilute India's negative image to investors abroad and its investment destination countries. This is particularly important after India's criticised move of liquidating Deva's corporation in the Devas- Antrix deal to deny it the $ 1.29 billion compensation awarded by the International Chamber of Commerce against India, which resulted in huge losses for Devas' foreign investors.

ASSESSMENT:

- Reasons why sovereign debts occur may vary- sanctions and asset freezing for Russia and fiscal mismanagement in Sri Lanka, but every affected country's economic, social, political and developmental fallout is the same.

- Despite several political commitments made by the international community, the sovereign debt crisis continues to constrain the development prospects of many low and middle-income countries. The austerity measures linked to loans and debt relief often degrade living conditions and limit investment in accessible public services.

- Decisive debt restructuring, debt transparency, responsible and democratic handling of public funds, medium-term debt management strategy, limiting fiscal deficit and appropriate legislation can go a long way in preventing a sovereign debt default.

Comments