Schooling the Migrating Millions

September 9, 2023 | Expert Insights

Seasonal migration is a widespread practice in India as people in rural areas look for livelihoods after the harvest. In fact, wealthier states like Punjab and some in the South depend heavily upon migrant labourers from other states to harvest their crops. In true gypsy style, migrant workers have travelled bag and baggage with wives, children and old parents in tow, constructing makeshift shelters wherever they are engaged and then moving on to the next job, whether in someone's fields or on a construction site.

Back in the last century, with joint families still intact and self-sustaining in the village, wives and progeny were left behind; not so increasingly now when the village support ecosystem is fading away.

Climate warriors tend to claim that drought and climate catastrophes are leading to an increased trend in "distress seasonal migration".

Hidden amidst the squalor of this vast human resource flowing from one town to another, fuelling the economy of rising India, are the millions of children being denied their basic fundamental rights. After all, the Constitution (Eighty-sixth Amendment) Act, 2002 inserted Article 21-A in the Constitution of India to provide free and compulsory education of all children in the age group of six to fourteen years as a Fundamental Right in such a manner as the State may, by law, determine.

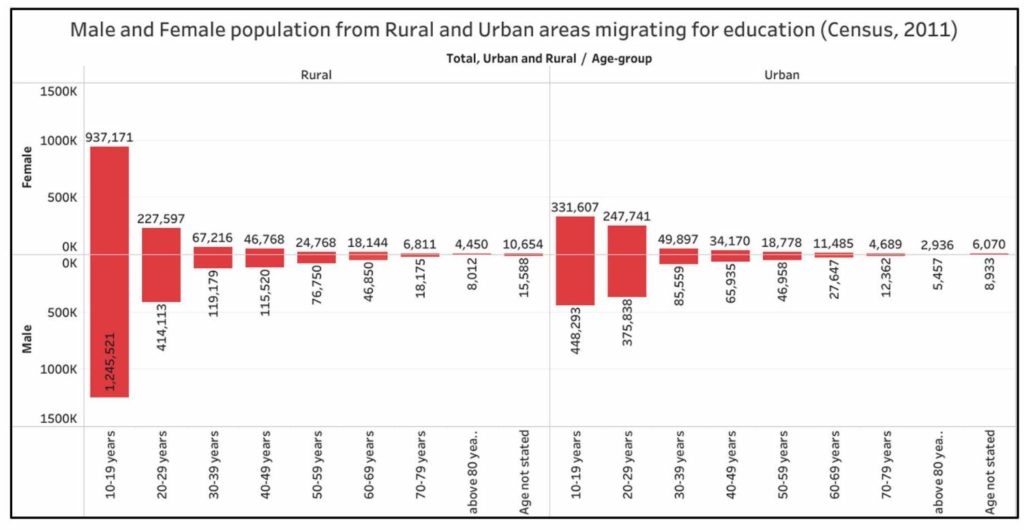

As per the Bangalore-based website Citizens Matter, over the last three decades, India has seen an increase in internal migration, from 232.11 million in 1991 to 314.54 million in 2001 and 455.78 million in 2011. The total number of migrant children between the census of 1991 and 2011 grew from 44.35 million to 92.95 million. As per these figures, one in every five internal migrants is a kid. A majority of them do not get access to basic education.

Background

Education plays an important role in several social and economic outcomes. Improving access to education can improve key outcomes such as employment, income, physical and mental health, well-being, socio-economic mobility, and more. The extent of education also has ramifications for society in terms of GDP, social welfare spending, crime rates, social cohesion, and political engagement.

Seasonal migration usually involves migrants travelling from poor and underdeveloped rural regions to more developed regions with higher demand for labour – typically industrial or agricultural labour. Internal migration in India almost doubled in the two decades between 1991 and 2011. Seasonal migration mostly takes place after the harvest of the monsoon crop (kharif) when there is a lack of livelihood options.

This trend has increased in recent years because of problems created by climate change, such as persistent drought and disrupted rainfall patterns. Climate variability has been found to reduce agricultural yields and incomes, which can pressure people to migrate out of financial distress. As a predominantly agrarian country, India is particularly exposed to the risks. A weakening monsoon, rainfall deficits, and drought significantly affect rural agricultural households.

In addition to these "push" factors, there are also "pull" factors for distress migration, such as the high demand for labour in destination areas. Migrant labour is particularly prevalent in sectors like brick production, salt production, sugarcane harvesting, stone quarrying, construction, fisheries, and plantations. Distress migration is a reality in nearly all states in India.

Seasonal migration usually begins in October or November. Migrant families spend six to eight months at the work destination and return to their villages before the monsoon. This cycle overlaps with six to eight months of the school calendar: migrant children can attend school only from June to October or November.

Analysis

Children accompanying their migrant parents miss several months of school but often remain nominally enrolled at their schools. If they resume school when they return, they grapple with learning gaps caused by their absence. Joining a school at the destination is difficult because there are often no schools located near the work site. It is also difficult because they arrive in the middle of the academic year, and schools don't offer support measures for this. Other obstacles are the different language and curriculum in the new location as well as the fact that the parents are occupied on the work sites and not available to support the children. Children often have to repeat the same class multiple times, which impedes their educational progress.

On the other hand, children who stay behind at the source village experience challenges due to their parents’ absence. These include lack of support in their schooling (such as for stationary supplies), lack of supervision resulting in reduced academic performance, and even behavioural and psychosocial issues, which affect their ability to keep up with their curriculum. Children of migrant households have been found to lag in terms of school attendance and continuance of education. Further, because of their parents’ migration patterns, the children are often difficult to track and can easily be left out of systemic interventions such as alternative and flexible school options.

It must be noted that migrants predominantly belong to marginalised segments of society such as Scheduled Castes (SC), Scheduled Tribes (ST), Other Backward Castes (OBC), the landless and land poor, and those who have the least assets, skills, or education. Around 83 per cent of seasonal migrants recorded in the National Sample Surveys of 2005, 2010, and 2012 belonged to communities officially recognised as socio-economically disadvantaged.

Further, distress seasonal migration often manifests as an inter-generational pattern: in several sectors, it carries through three, four, or five generations. When children of migrant households drop out of school, it continues the cycle of socio-economic disadvantage.

Seasonal migration of parents particularly affects girls’ access to education. By the time they reach Class 7, the dropout rates are higher for girls than boys. The long distances that need to be travelled to reach school, coupled with the lack of safe and affordable transport arrangements, make it difficult for girls to continue schooling. Girls also end up taking up domestic responsibilities. Older daughters often accompany the parents when they migrate to look after the younger children while the parents are at work. Similarly, stay-back daughters have to look after younger siblings or grandparents in their parents’ absence and manage household chores.

Policies that seek to improve migrant children’s access to education need to take into consideration the special requirements these children face. Schools need to incorporate measures that help bridge the learning gap and resolve the discord between the fixed school system and the mobile lives that migrant children live. Flexible curriculum, bridge courses, remedial support systems, and multilingual teaching are some measures that could help.

A comprehensive national policy for seasonal migrants can be developed along with a database that keeps an accurate record of data on seasonal migrants. States could be required to maintain migrant portals with data on incoming and outgoing migrants and their families. This would help ensure that migrant families can still access social services related to food, health, and education. It would also allow for educational interventions to account for and accommodate migrant families.

As per a World Bank blog of June this year, some Non-government organisations (NGOs), through multiple interventions and policy responses, have contributed significantly to ensuring education for migrant children. However, considering the spread, extent and multi-locations of internal migrants and children, their efforts are insufficient. Hence, there is a need for a robust education inclusion policy with solid support from the government. Therefore, one needs to scale up the state-NGO collaborations and collective initiatives by interstates at the earliest.

Assessment

- Seasonal migration poses a substantial challenge to the education of migrants’ children. In several cases, the disruptions and hurdles lead to them dropping out of school altogether. Girls are most affected by their parents’ seasonal migration because they usually have to take up domestic responsibilities.

- Currently, the lack of data on seasonal migrants and their children makes it difficult to target the issue and strengthen the educational inclusion of migrants’ children. This has to be rectified soonest.

- It is about time India addresses the pressing needs of education faced by migrant children in a holistic manner. NEP 2020 also talks of ‘equitable education’ as does the UN SDGs, but there seems to be little movement on the ground apart from some charitable groups conducting ad hoc classes under tents in large construction sites in some metros. Much more is needed to be done.

Comments