Running Out of Steam?

September 16, 2023 | Expert Insights

With the second largest economy in the world, China has long been associated with an upward trajectory of economic growth. In fact, during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, China was the only major developed economy that avoided going into a recession.

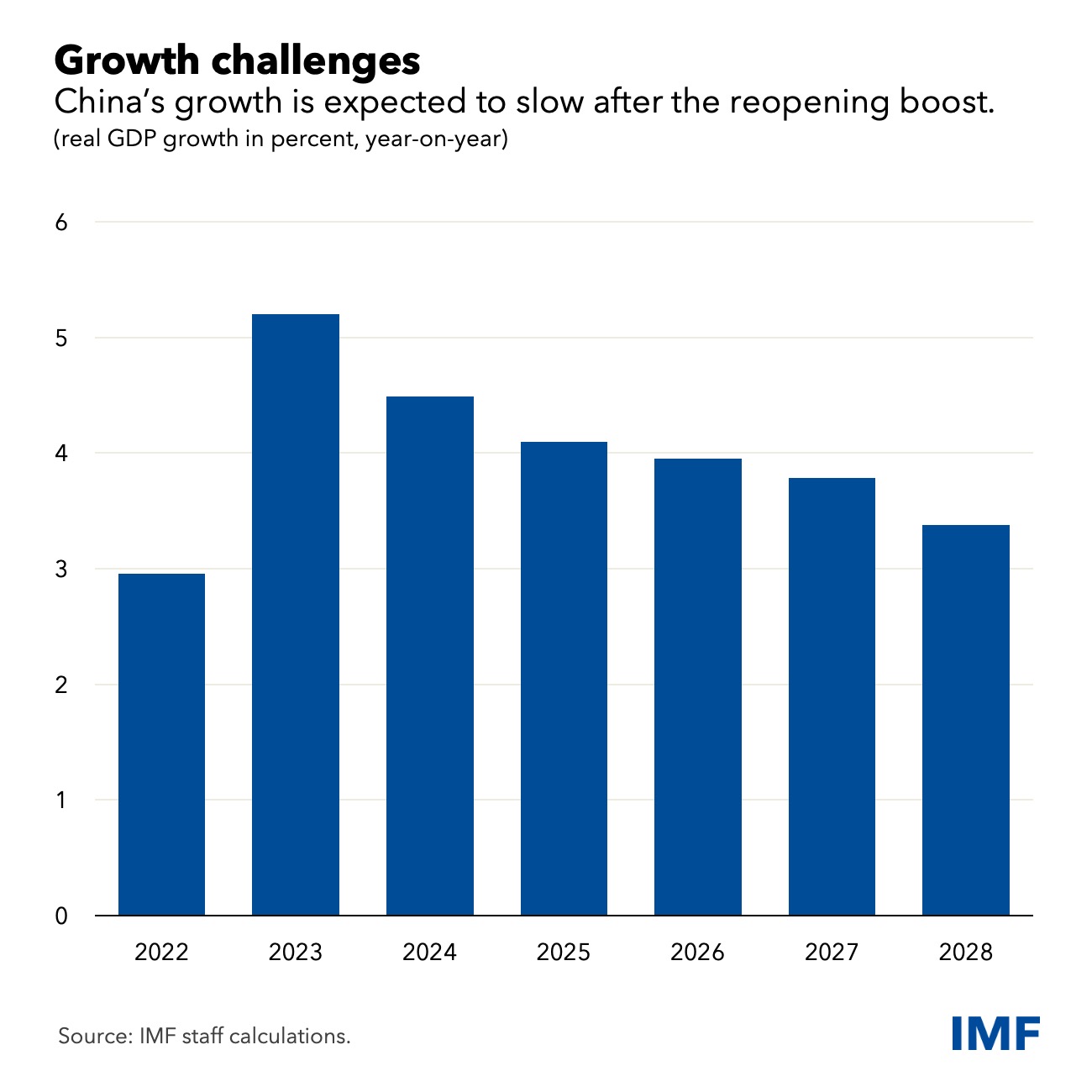

After three years of stringent zero-COVID lockdowns, China’s economy was expected to recover this year. However, not only has it failed to pick up pace, but its growth is slowing down as it grapples with a real estate slump, local government debt, reduced consumer spending, unemployment and more.

This has global ramifications as China’s economy is one of the major engines of the world economy.

Background

China’s rise over the last 50 years is one of the leading examples of an economy that opens to global markets and witnesses significant transformation. From a predominantly agrarian society to an industrial powerhouse, China has witnessed sharp rises in productivity.

The first twenty years after the People’s Republic of China was established in 1949 witnessed substantial growth in per capita GDP (output per person), with large-scale, capital-intensive projects boosting China's industrial pace and productivity. However, markets were restricted during the “Great Leap Forward” from 1958 to 1962. When these measures were withdrawn, the economy witnessed another period of increased productivity and per capita GDP from 1962 to 1966 until the Cultural Revolution, when it again suffered an economic slowdown.

Subsequent major reforms initiated the process of economic liberalisation. In 1978, reforms began the shift from collective farming to the household responsibility system, where households became individually responsible for production. A year later, a new law allowed foreign capital to enter China, and by the mid-1980s, the government allowed companies to retain profits and set up their own wage systems. This helped increase GDP from an annual average of 6 per cent to 9.4 per cent in the period between 1978 and 2012. It also facilitated urbanisation as higher-paying city jobs drew workers from the countryside. By the end of this process of economic liberalisation, China became a major global exporter and overtook Japan to become the second-largest economy. China has continued this economic model that combines liberalisation with state control.

During the 2008 global financial crisis, China revived its economy with the largest stimulus package and became the first major economy to emerge from the crisis. In 2013, it launched its ambitious global Belt and Road infrastructure initiative, which has slowed down due to domestic economic problems.

Analysis

The general expectation was that China's economy wouldwould recover after the zero-COVID lockdown this year. This was expected to be led by a revival of consumption sparked by economic activities resuming as normal. However, in light of its slowing economy, China may struggle to meet its growth target of around 5 per cent for 2023 without further government expenditure. In fact, even 5 per cent growth this year would not be as much as it seems, considering that it was under zero Covid measures in 2022, which sets a low bar for increase. The revenge spending that many expected to take place as the Covid restrictions were lifted did not take place. Further, as countries across the world deal with higher living costs and inflation, global demand for Chinese exports has reduced.

A slump in the real estate sector is one of China's most significant economic problems, spilling over to other aspects of the economy. Given that the property market comprises about a quarter of economic activity, it is unlikely that China will be able to address its falling economic growth. Debt-based government spending on infrastructure and property has led to a build-up of debt, the property bubble has now burst, and exports are slowing with the global economy. This brings the focus to the last source of demand – household consumption.

However, even before the pandemic, household consumption in China was among the lowest in the world. With youth unemployment rates now above 21 per cent, yuan deflation shrinking profit margins, and slow recovery from the Covid crisis, household spending does not seem likely to increase. Further, 70 per cent of Chinese household wealth is tied up in real estate, which is under stress, leading to tighter spending as people feel their property is worth less. People are not spending on food and beverages, retail or tourism, bringing key services under pressure. Ways to improve household spending could include tax cuts, encouraging wage growth, providing social security with higher pensions, and more accessible public services.

Low consumer demand and reduced international demand affect manufacturing and output. Profits in the iron and steel industry alone fell by more than 80 per cent in the first seven months of 2022. A regulatory crackdown on major tech companies for two years has also affected investment and employment. In the most recent quarter, Tencent’s profits and Alibaba’s net income fell by 50 per cent. Foreign investors are pulling back as successful private companies come under increased scrutiny. In addition to declining trade and investment, the yuan has slipped into deflation: it fell to a 16-year low against the dollar in August.

While Beijing has taken certain measures, it has not introduced major reforms as in the past, such as in the 2008 financial crisis. However, the reforms then hiked up local government debt, which the economy is still recovering from. Concerned about its systemic municipal debt, China is being cautious in its reforms this time. In the face of fiscal stress, local governments have tightened their fiscal policies. This, in turn, has reduced government support for economic growth and public services and affected consumer spending.

The Chinese economy also faces long-term challenges. In addition to a declining and ageing population, reduced migration from rural to urban areas has also contributed to falling housing demand. A smaller workforce could also decrease domestic savings, leading to higher interest rates and less investment. Further, China’s relations with major trading partners such as the United States and Europe are strained, particularly in light of its support for Russia in the Ukraine war, increasing polarisation between the West and Russia and China, as well as intensifying US-China rivalry.

Assessment

- The larger outcome is that China’s growth trend has substantially reduced since the pandemic began and seems set to fall further.

- Along with low consumer demand and high unemployment, the real estate slump is a key facet of China’s economic slowdown. The government will likely ease property restrictions to stabilise the property market and perhaps provide credit to prevent developers from defaulting.

- Other measures to stimulate the economy could include providing incentives for manufacturers. Policy changes have so far been incremental due to high public debt.

Comments