Quenching Afghanistan’s Thirst

August 12, 2023 | Expert Insights

Hidden amidst all the negative reporting streaming out of Taliban-controlled Afghanistan- the poverty, food shortage, denying basic rights to women, etc-is a story of hope for the blighted Afghan people. A dream scripted almost half a century back shows signs of turning into reality as the Taliban goes ahead with an ambitious civil engineering project to bring the waters of the Amu Darya to its thirsty northern plains.

But like all things connected with Afghanistan, this canal, too, will have a ripple effect across its borders. While Central Asia may be rich in gas and oil, it runs short when it comes to basic water. Climate change and water-intensive cultivation like cotton crops aggravate its perennial water shortage and aridity. However, a new canal rapidly being built by the Taliban in Afghanistan threatens to exacerbate water security issues in the region.

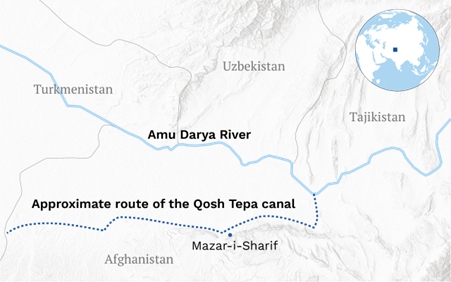

Water wars are a reality in this region inhabited by fierce warriors who need little excuse to fight. Disputes over water sharing often break out between the downstream countries – Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan – and the upstream countries - Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Afghanistan's dream project, the Qosh Tepa Canal (named after the Qosh Tepa district in the Jawzjan province), could be the tipping point to turn these tensions into an open conflict. Simply put, the precious waters of the Amy Darya, so far, the exclusive resource of upstream countries like Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, who have been using water from the river since the Soviet era, will also be meeting the demands of a water-stressed Afghanistan.

Background

Under the iron hand of the Kremlin, water-sharing agreements were force-fed to the bickering nations of Central Asia during the Soviet era. However, in a hurry to rush water to huge collective farms carved out of the steppes of Central Asia, no scientific research was done on its long-term implications as this water-deficient region has few river systems to play around with. The death of the Aral Sea in the same region is a terrifying example of a man-made disaster at an epic scale. The Soviet Union focused only on economic output rather than sustainable irrigation practices, with disastrous consequences.

After the five countries- Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan- gained independence in 1991, the old water-sharing schemes continued, and Soviet-era allocation quotas are still followed. Naturally, Afghanistan remained out of these agreements.

The countries have attempted to create frameworks for cooperation, such as the Almaty Agreement of 1992, the Interstate Commission for Water Coordination of Central Asia, and other bilateral and multilateral agreements. However, these agreements lack force since they are weakly implemented and not precisely defined. The lack of regulation has created an unstable situation where each state strives for access to water, often resulting in conflict with other states.

The upstream countries (Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan) use water to generate electricity. In contrast, the downstream countries (Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan) mainly rely on it for agriculture, such as food and cotton production. This situation results in disputes between the upstream countries and downstream countries. The former are keen to gain more control over their resources, while the latter need water for agriculture to support growing populations. Downstream countries are vulnerable to dams and hydro projects set up by upstream countries, which affect the water available for their agriculture.

Under its centralised planning, the Soviet Union compensated upstream countries with fuel, coal, and gas in return for downstream countries using their reservoirs. However, these arrangements are hard to maintain under present circumstances. Water scarcity is increasingly exacerbated by climate change and growing populations with accompanying food security challenges. Rising temperatures have increased water loss due to evaporation and also led to glacier melting, which will diminish the water supply to rivers in Central Asia in the long run.

Armed clashes over water erupted between the Kyrgyz and Tajik armies in 2014 and 2016. The Ferghana Valley, which spans Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan, is particularly prone to violent water conflict with increasing water usage and disputed borders.

Meanwhile, aridity, climate change, and food insecurity are issues that Afghanistan faces too. For more than 50 years, it has been considering constructing a dam to divert the water of the Amu Darya River to irrigate its dry Northern plains. However, regime changes and unceasing conflict have prevented the canal's construction. The Taliban has now taken up the vast project, and it is rapidly progressing.

Analysis

The canal is a long overdue development project for Afghanistan that will help it overcome food insecurity. 80 per cent of its population relies on agriculture for sustenance. So far, its poor infrastructure and history of conflict have prevented it from constructing projects to better use water resources.

No doubt, the desperate food situation has forced the Taliban regime to get this project completed in the least possible time if it wishes to significantly reduce its dependence on foreign food handouts. Fazullah Akhtar, an Afghani working as a senior researcher at the University of Bonn, was quoted in an article on the website The Third Pole, “The current policies of the ruling regime have had disastrous impacts, with 20 million people acutely food-insecure, including six million on the brink of famine,”

The canal was estimated at 684 million dollars and had been in the works for several years before the Taliban came to power. It was initiated under Afghanistan's former US-backed government with support from the USAID development agency, which funded the feasibility report for the study.

Funding for the project may be an obstacle. Since no foreign donor is willing to finance the mega project, it will be funded using domestic government revenue and national resources. The Taliban is determined to complete the canal and has prioritised it with limited state resources. The funds for the second and third phases of the project will be raised by selling mines, especially the Dar-e-Souph Mine. There is also scepticism towards the project based on the lack of expertise and know-how supporting it. Spearheaded by Afghanistan's National Development Company, more than 200 companies are involved in the project, but there is no assistance from international donors or international financial organisations yet.

Afghanistan is not a party to any water-sharing agreements with its Central Asian neighbours. Amu Darya's water has been allocated between Central Asian countries based on the Almaty Agreement. While the five countries have other water-sharing agreements, Kabul is not a part of them. The region's Water access is mainly through the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya.

Once the 285 km-long Qosh Tepa canal is completed, it is expected to channel 25 per cent of water supplies from the Amu Darya basin to Afghanistan. This would significantly impact the water supply to downstream countries Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, which are already facing water scarcity and aridity. Turkmenistan draws the majority of its water supplies from the Amu Darya. Uzbekistan relies on water for its crops, particularly its cotton crops, which form a significant part of its agriculture.

The countries will likely enter into bilateral or multilateral negotiations to devise a framework for sharing the water of the Amu Darya. Since the two affected countries supply critical energy resources to Afghanistan, there is some pressure on the Taliban to negotiate with them. Uzbekistan supplies electricity to Afghanistan, and Turkmenistan supplies Afghanistan with electricity and gas. Furthermore, Afghanistan's exports, however little, travel on these routes passing through these countries. Without an agreement or understanding with other countries in the basin, the diplomatic crisis could further isolate the Taliban in the region.

India View

As part of India's search for energy security, the vast gas resources of Central Asia are an attractive option, making the Asian Development Bank-backed TAPI (Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India) pipeline project of great interest to New Delhi. While Pakistan, too, stands to benefit from transit rights and cheap gas, the major block lies in conflict-ridden Afghanistan. On their part, the suppliers-Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan- have been keen to convince Kabul to cooperate on TAPI as they have already invested significant resources in the pipeline project. The canal project could provide just the leverage needed to get TAPI off the ground.

The Taliban recently announced that TAPI construction would resume, which could result in the concerned states getting returns on their investments. India, which is interested in diversifying its oil imports, would be one of the major beneficiaries of the project. On the other hand, if Qosh Tepa aggravates neighbourly relations, it could also kill TAPI. This is something India has to be wary of as it has invested over 200 million as initial payment in the $20 billion project. Similarly, the collapse of TAPI will not be good news for Pakistan, energy deficient as it is and in a position to buy the expensive Gulf crude.

While Pakistan's water supply is not affected by the canal, India and Pakistan stand to benefit from a diplomatic agreement between the Central Asian countries and Afghanistan for sharing water. Since Afghanistan is a key link between Central Asian countries and India and Pakistan, tensions and hostility between the Taliban and Central Asian countries could impact trade between Central Asia, India, and Pakistan.

Assessment

- The pressure of climate change, growing populations, and water-intensive cultivation have exacerbated water scarcity issues in Central Asia. The massive irrigation canal will likely increase tensions over water-sharing in the region - particularly between Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan. Even countries like India and Pakistan, not involved in water sharing, will be geopolitically impacted.

- The lack of precise and effective water-sharing agreements between Central Asian countries is a key issue that needs to be addressed. Additionally, countries in the region will have to upgrade their irrigation methods by adopting sustainable cultivation techniques to avoid further water conflicts.

- The need to maintain harmonious relations for regional security and trade continuance will likely encourage the affected countries to negotiate a framework for sharing the Amu Darya River water.

Comments