PUTTING FOOD BEYOND REACH?

June 10, 2022 | Expert Insights

Two years of pandemic induced economic woes have been made even worse by the war in eastern Europe, which is refusing to die. Natural and man-made episodes of such magnitude have set up a resonance that is playing havoc with the lives of both rich and poor in almost every country in the world.

Background

After the famines of the late 1960s, the dismal memories of foreign food handouts rationed through the public distribution system faded from our memories as India moved towards food self-sufficiency. Food security became, for the average Indian, something to be taken for granted. Decade after decade, Indian farmers harvested bumper crops thanks to scientifically nurtured resilient seeds and generously subsidised stock of imported fertilisers and free electricity. However, now a fractured global economy is taking a toll on all segments of the Indian economy, including the food industry.

As per Dr Amarendar Reddy, Principal Scientist at ICAR-Centre Research Institute for Dryland Agriculture, the spectre of uncertainty in global food supply looms ominously in the future. The risk may increase in the next 10-20 years because the global geopolitical situation is very volatile. The Ukraine-Russia conflict, it is feared, may cause deep fractures within the existing geopolitical landscape to the extent that instability may last for many years.

In addition, there is a plethora of other international and internal conflicts, climate change and geo-economic political situations, which are soaring global risks. There has been a sharp rise of 50-60 per cent in the prices of food, fertilisers, fuel and edible oil in recent years. Rising food prices have a greater impact on people in low- and middle-income countries, especially India since they spend a larger share of their income on food than people living in high-income countries. A strong dynamism is required to cater to this problem, especially for the vulnerable sections of the world.

Russia and India are known as the food basket, especially for most of the countries in Africa and South Asia. Sanctions have throttled supplies from Russia and Ukraine. Poorer than expected cereal harvests due to unusually high temperatures in India have made the government ban export of wheat. Russia and Ukraine also supply the world with edible oil, and India, as one of the top global importers of this commodity, is 50 to 60 per cent dependent on Russia. Thus, all indicators point towards a volatile food market.

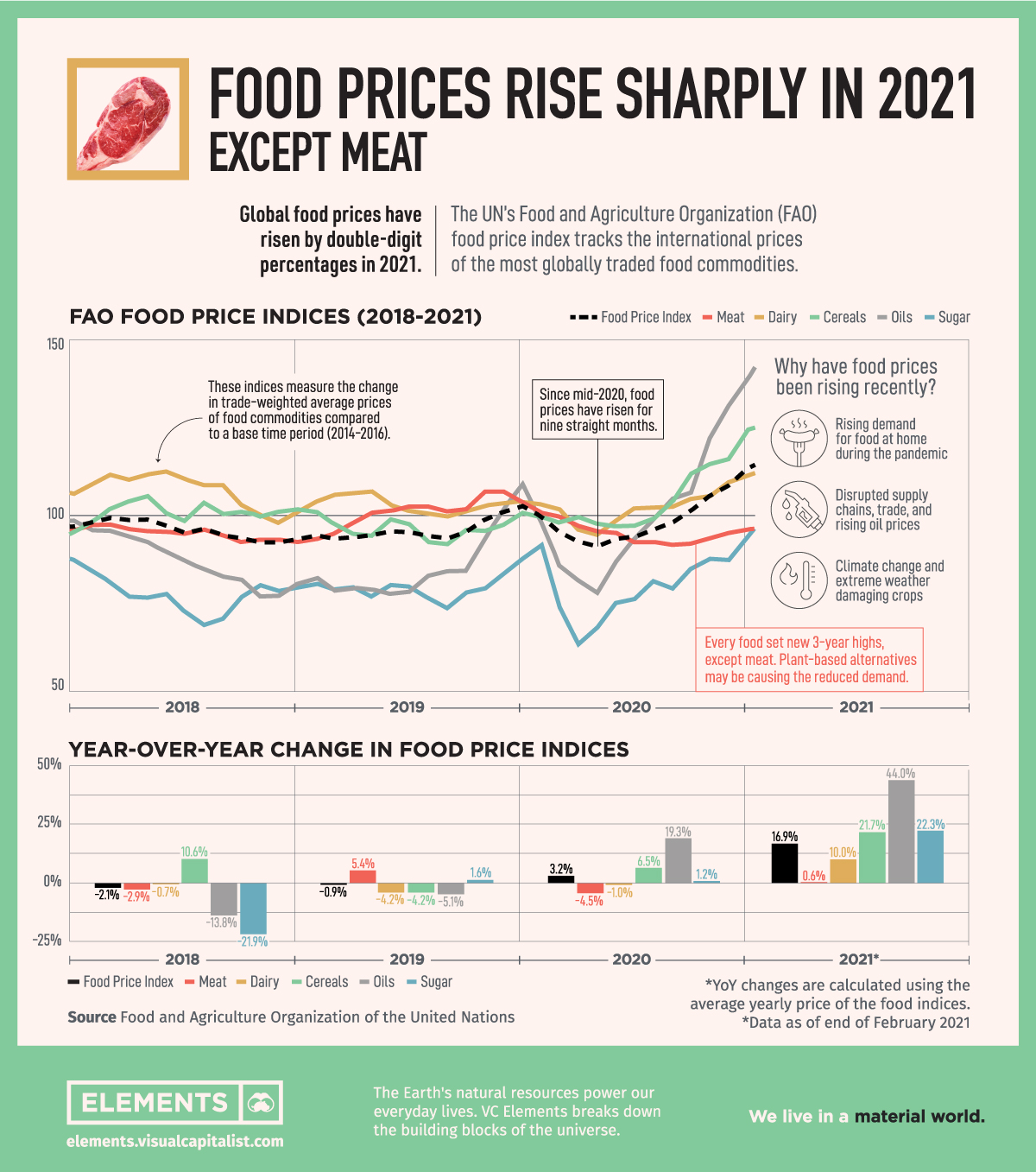

With the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation's (FAO) food price index hitting all-time highs, it has reignited the memories of the last great commodity inflation. That was during the period from the mid-2000s till around 2012-13, briefly interrupted by the 2008-09 global financial crisis.

Analysis

Food inflation in India is expected to be 5.50 per cent by the end of this quarter, according to Trade Economics global macro models and analysts’ expectations. The same models predict that the India Food Inflation will trend around 5.50 per cent in 2023 and 4.30 per cent in 2024.

Indian fertiliser subsidy expenditure increased from 70,000 crores to 1,30,000 crores marking a stunning 50 per cent increase. The impact on the overall economy of such a sudden rise can well be imagined. The solution lies in formulating long term strategies for the import of fertilisers by arriving at covenants with global suppliers like Russia and Ukraine (after it has recovered its war-devastated industry) for the next decade or so. This will ensure a constant supply at reasonable rates. Such initiatives will result in a stable fertiliser bill and a stable agriculture sector for India and our farmers will earn a reasonable profit for their products.

To deal with such uncertainty and unexpected disruptions in the supply chain, India must enhance its domestic capacity for fertiliser production. This can be achieved with collaborative research and development taking the lead. The use of resources such as germplasm (living genetic resources such as seeds or tissues that are maintained for the purpose of animal and plant breeding, preservation and other research uses) will result in increasing the productivity of Indian agriculture.

Indian agriculture faces non-tariff barriers in key export markets compared to the products from other developing countries. These rejections can lead to financial losses in the short run, accompanied by exporters and farmers losing market share to exporters from other countries in the long run. These contrivances need to be minimised by multiple interventions.

Nowadays, there is a regional buffer stock maintenance in Asia and in European Union that will be helpful in reducing the price inflation pressures across the globe. To swiftly move these reserves from one continent to another, there must exist an adequate infrastructure, road network, and sea network to increase the interconnectivity. The Chinese Belt and Road Initiative could prove especially useful in such contingencies as it links vast swathes of remoter areas in Asia and Africa.

Just like oil security, wherein India has gone for long term contracts and even invested in oil extraction and distribution infrastructure in the producer countries, food security needs an identical approach. India must go for long term contracts with oilseed producing nations like Russia, Ukraine, Indonesia, and Malaysia, so that market volatility does not impact the farmers producing these commodities. Once the producers are assured of a good price for a period, they are unlikely to shift to other cash crops or, in times of global shortages, raise prices to make a killing.

These contracts should not only be limited to edible oils but also for ammonia-based fertilisers, including Urea, Di-ammonium phosphate (DAP) and potash from Russia, Ukraine and other countries.

Assessment

- A combination of new and ongoing stresses has been playing havoc with the world food situation and, in turn, the prices of food commodities. One emerging factor behind rising food prices is the high price of energy. Energy and agricultural prices have become increasingly intertwined. So, till the energy market cools, food prices will not come down.

- Countries are reacting in a manner that is in their best interest; India has banned the export of wheat, while for a time, Indonesia stopped its lucrative edible oil exports. Food importing nations will have to economise on their food shopping lists by cutting down on so-called luxury foods and setting limits on food prices, and hoarding through rationing.

- The real answer lies in creating long term strategies for food security. This should focus on agriculture growth and encourage medium- and long-term investments in agriculture research, rural infrastructure and market access for small and marginal farmers

Comments