Is the Indian Ocean No Longer Indian?

April 8, 2023 | Expert Insights

The Indian Ocean has been a major interconnecting waterway throughout its history. As India grows in importance on the world stage, this stretch of water around its periphery assumes critical relevance to its future prosperity and security.

The American geostrategic realignment on the Indo-Pacific vis a vis the European theatre has rightly been seen by China as challenging its own pre-eminence in the region. Therefore, a counter from Beijing, both in the Pacific and the Indian Ocean, is a natural corollary to this apprehension.

While it struggled with its economic growth and external wars in the first 50 years since independence, India took for granted the security afforded to its peninsular land mass by the vast expanse of the Indian Ocean, concentrating its limited resources on its land frontiers. However, an ambitious blue navy projection has always been part of India's long-term calculus, and as its coffers grow, the long-standing ambition is emerging. Therefore, it is unsurprising that apart from the high Himalayas, the Indian Ocean would assume the arena for Sino-India rivalry.

Recently, China reiterated its vehement opposition to the Indian Ocean being named after India while at the same time claiming 'historical justification' for the naming of the South China Sea. While this statement may sound whimsical, the larger message is China's relentless effort to hammer home its claims to all the seas around its land mass and critical to its economic and political security.

Background

Like India, the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) too has always kept a close eye on the Indian Ocean. This was to be expected because since China became the global manufacturing hub in the late 1980s, its manufactured exports and raw material imports,, including precious oil,, flowed into its factories through the northern reaches of the Indian Ocean. But lacking a true 'blue water navy,' it bided its time.

As far back as 2004, the U.S. consulting firm Booz Allen Hamilton was talking about a "string of pearls" hypothesis with respect to China's increasing naval presence in the Indian Ocean. It talked about the Chinese construction of civilian maritime infrastructure along the periphery of the Indian Ocean. The Chinese were thinking much ahead at the time as the West had yet to develop any Indo-Pacific policy. Also, in the later part of the 20th century, big power tensions in the Indo-Pacific during this period were nothing like now. Therefore, the universal law of freedom of seas assured PRC of uninterrupted trade flow across the Indian Ocean.

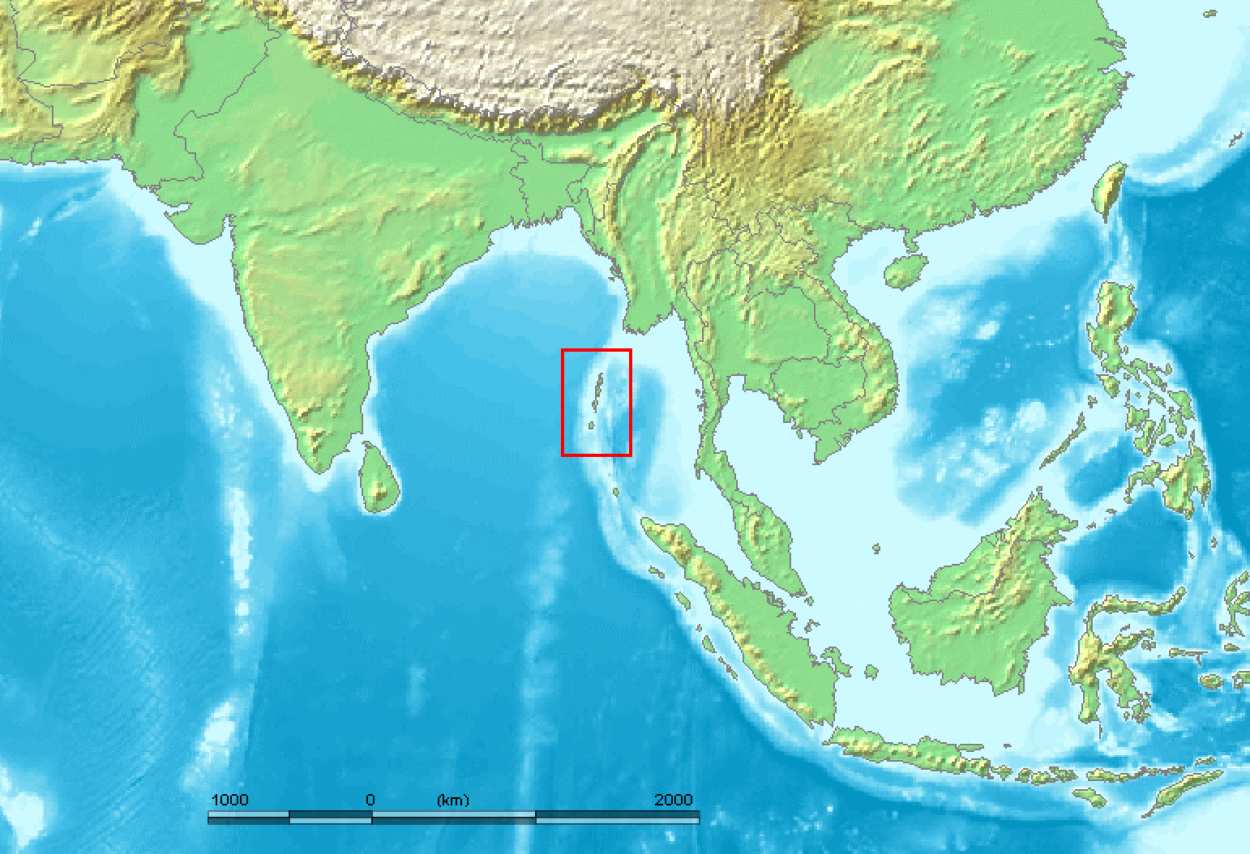

With the advent of the 21st century, the power equation in the world began to change in favour of Beijing. Slowly PRC expanded its influence, backed by military power around its periphery, starting with the South China Sea, where it has serious territorial disputes with almost all the other littoral states. And South China Sea is not far from the Indian Ocean; the narrow Kra Isthmus connects the two waterways. Looking for a way out of the potential stranglehold imposed on Chinese commercial and naval shipping by the narrow Malacca Straits, China has proposed to Thailand a $20 million canal across the Kra Isthmus.

This has serious security implications for other regional countries, especially India, as this would give China an exclusive safe maritime corridor linking Chinese ports elsewhere in the South China Sea to the Indian Ocean. Due to external pressure, the proposal did not make much headway initially, but later in 2014, a Memorandum of Understanding was signed, “China-Thailand Kra Infrastructure Investment and Development Company and Asia Union Group” in Guangzhou.

China’s initial incursions into the Indian Ocean were mostly commercial in nature. Beijing did not want to ruffle feathers by bringing in a military component right from the beginning. So, China had commercial ports owned and operated by Chinese firms along with resupply stations that operated in agreement with the government of the People's Republic of China. These ports were Gwadar in Pakistan, Hambantota in Sri Lanka and Sittwe in Myanmar. Each of these ports is strategically located in the Indian Ocean. They allow Beijing to access other Indian Ocean littoral countries. In return for offering these port facilities, each of these countries has embarked on a symbiotic economic relationship with China.

Analysis

It was evident early on that China's interests in the Indian Ocean would not be restricted to trade and economic partnerships. The Indian Ocean by itself might not be that important for Beijing, but as a part of the wider Indo-Pacific region, its significance increases by many times. The Indian Ocean is also where China can take its military rivalry with India to the maritime sphere along with the border disputes it already has with New Delhi. Thus, this could be part of a broader strategy of hemming in India from the land and the sea.

The growing Western military presence in the Indian Ocean is also a cause of concern for the PRC. Because the Indian Ocean is a part of China’s global maritime expansion, Beijing believes that the West will cut it off from this by containing it in this ocean. And it is not just one Western country that has become increasingly involved in the Indian Ocean. Multiple countries and regional powers like India and Japan are engaged in this area. Both New Delhi and Tokyo are further involved in informal military coordination through the mechanism of the Quad. As members of the Quad, Australia and the United States also participate in these military exercises. AUKUS, which will introduce nuclear-powered attack submarines into the calculus, is another factor that challenges Chinese hegemony.

So, what is to be made of the most recent Chinese statement on the Indian Ocean? Does it signal a recalibration of official policy?

The recent statement was made by officials from the Chinese defence ministry and high-level think tanks associated with the People's Liberation Army (PLA), like the National Defence University. This changes the context in which this statement was made considerably. This is the viewpoint of not just one branch of the Chinese government but the entire defence and foreign policy establishment in Beijing.

The level of interaction between the Indian and Chinese navies in the Indian Ocean has increased substantially over the years. This was bound to happen as the activities of the People's Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) in the Indian Ocean increased with time. China has been engaged in anti-piracy efforts in this ocean since 2008.

India has also tried to expand its reach to the Pacific Ocean and the South China Sea. So, Beijing is not the only one that is going out of its comfort zone.

China also considers the South China Sea within its sphere of influence. So, the situation is reversed between New Delhi and Beijing here, compared to the Indian Ocean.

Beijing does not deny the fact that India has a special role to play in the Indian Ocean, much like China thinks it has in the South China Sea. However, the Chinese argue that this does not mean the Indian Ocean should be the exclusive zone of interest for India and a few other like-minded countries. Here China uses the same argument that the United States uses for the South China Sea. This is because the Indian Ocean is an international body of water where all countries should have an equal right to navigation.

According to the Chinese, if the Indian Ocean truly falls within India's sphere of influence, then other countries like the United States, Australia and Russia should also not have navigation rights in these waters. But this is not the case, and China is a little hypocritical here as it does not consider the South China Sea to be international waters in the same way.

Organizationally, China is also spreading its influence in the Indian Ocean. It is doing so by setting up rival organizations against existing ones in the region. The Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA), of which India is a member, has been set up to promote regional economic cooperation. China is not a part of this grouping. So, it has established a parallel entity called the China-Indian Ocean Region Forum with similar objectives.

Assessment

- As the level of interactions between Beijing and New Delhi has increased in the Indian Ocean, there is also the corresponding need to expand the channels of communication between the two sides. This prevents any inadvertent incidents between the two sides due to misunderstandings.

- India, on its own, cannot stop this Chinese advancement. It has to coordinate its maritime outreach with other major regional naval powers apart from the U.S.-Japan, Australia and Vietnam.

- Chinese outreach to the Indian Ocean is linked to Beijing’s Indo-Pacific policy. With increasing tensions in the wider Indo-Pacific region, China wants to secure the Indian Ocean rear end. This issue will gather pace as China expands its naval capability, and India must accordingly switch focus from its terrestrial obsession to a maritime strategy with the capacity to put it in effect.

Comments