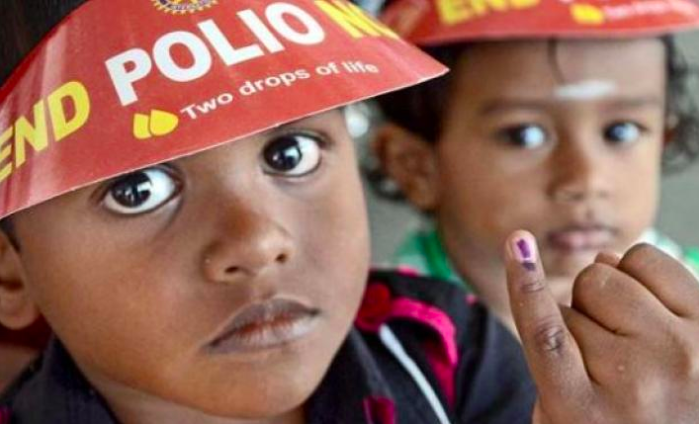

India’s Polio Immunisation Crisis

November 19, 2018 | Expert Insights

The sole supplier of inactivated polio vaccines to India is likely to raise its price per dose in the coming years as a result of a global shortage of IPV. This leaves India’s polio-free status dependant on funding from an international organisation.

Background

Poliomyelitis, or polio, is an infectious disease caused by the poliovirus. In about 0.5 percent of cases, there is muscle weakness resulting in an inability to move. In those with muscle weakness, about 2 to 5 percent of children and 15 to 30 percent of adults die. The disease is preventable with the polio vaccine. Once infected, there is no specific treatment for polio. In 2016, there were 37 cases of wild polio and 5 cases of vaccine-derived polio. This is down from 350,000 wild cases in 1988. In 2014 the disease only spread between people in Afghanistan, Nigeria, and Pakistan. In 2015 Nigeria had stopped the spread of wild poliovirus but it reoccurred in 2016. Inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) replaced the oral poliovirus vaccine in the polio immunisation program in 2015, as it eliminates the risk of vaccine-associated polio paralysis. They are a key tool in the global polio eradication effort.

In India, vaccination against polio started in 1978 with the Expanded Programme on Immunisation. By 1984, it covered 60% of infants. In 1985, the Universal Immunisation Program was launched to cover all the districts of the country. UIP became a part of the child survival and safe motherhood program (CSSM) in 1992 and the Reproductive and Child Health Program (RCH) in 1997. This program led to a significant increase in coverage, up to 5%.

In 1995, following the Global Polio Eradication Initiative of the World Health Organisation (1988), India launched the Pulse Polio immunisation program with Universal Immunisation Program which aimed at 100% coverage. Gavi is an international global Vaccine Alliance that brings together the public and private sectors with the shared goal of creating equal access to vaccines for children living in the world’s poorest countries.

Analysis

The Ministry of Health in India has approached Gavi for funds for obtaining inactivated poliovirus vaccines for its polio immunisation programme. This is because Sanofi, the sole supplier of IPV to the Indian government, is raising its prices in response to a global shortage of IPVs.

A constrained supply of IPV has existed since 2015 and is projected to continue for several more years. This is due to difficulties with scaling up IPV bulk production, causing reduced availability from both manufacturers. The pressure on IPV supply has been further compounded by an additional demand from countries that were expected to make their own arrangement for IPV supply. New requests for IPV doses for use in eradication related supplementary immunization activities have also reduced the availability of supply. Gavi expects a greater supply will become available at lower prices with the arrival of new manufacturers, starting in late 2020.

Sanofi has IPV prices under a uniform worldwide price revision. According to a UNICEF document, the price for India is to increase from the current 0.75 euro (Rs 61) to 1.81 euros (Rs 147) per dose in 2019, and to 2.18 euros (Rs 177) per dose from 2020 through 2022. This would increase the budget requirement for the immunisation programme by INR 100 crore, putting a severe strain on the Indian Health Ministry’s budget, and promoting the country to seek support from Gavi.

The health ministry is scrambling to avert a possible stock-out of the injectable inactivated poliovirus vaccine. India depends on funding from Gavi for many of its immunisation programs including pneumococcal vaccines and rotavirus vaccines, among many others. Gavi has already disbursed $107 million to India for pneumococcal immunisation between 2017 and 2019 and has approved $55 million for rotavirus vaccines between 2018 and 2020.

Counterpoint

Data from the Indian health ministry shows there has been an increase in public spending on health. However, close examination of this data shows that while state governments have increased expenditure on healthcare, the central government has reduced funding to public healthcare programmes.

British MP Peter Bone recently questioned aid being provided to India, insisting that it was unnecessary to send over a billion pounds in aid to a nation that spent over 300 million pounds on its statue of unity in October 2018. It is interesting to note that the country’s allocated budget for its affordable healthcare scheme is about a hundred million pounds short of the budget for its statue of unity.

Assessment

Our assessment is that a stock-out of the inactivated poliovirus vaccine would mean the government would be forced to temporarily stop immunising infants with IPV, which could have disastrous consequences for India’s polio-free status. We believe that dependence on international organisations to ensure immunisations are due to India’s poor budget allocation for health programmes.

Comments