Himalayan glaciers in potential crisis

December 12, 2018 | Expert Insights

A NASA led study shows that glaciers in High Mountain Asia are moving slower and that the slow-moving glaciers have thinned the most over time. This could pose a threat to the future stability of the region.

Background

The Hindu Kush Himalayan (HKH) region is the source of 10 major river systems that provide water, ecosystem services, and the basis of livelihood to more than 210 million people upstream in the mountains and 1.3 billion people downstream. While the meltwater that flows from the 90,000 glaciers in High Mountain Asia is critical to the lives and livelihoods of the people downstream, its significance is much wider, because the snow and ice stored at high altitude would otherwise push up global sea levels if it all melted and ran into the ocean.

The 30-km long Gangotri glacier located in the Uttarkashi district of Uttarakhand is the primary source for the Ganga. River Yamuna has its origin in the Bandar Poonch glacier just above Yamunotri. The Alaknanda has its source in the Alakapuri glacier above Badrinath. The River Mandakini has its source in the Sumeru glacier above the Kedarnath Temple. The Bhara Shigiri glacier in the Chandra Valley of Lahaul in Himachal Pradesh feeds the Chenab river. The Zemu glacier is the largest in the Eastern Himalayas in Sikkim. It is at the base of the Kanchendzonga and is one of the sources for the Teesta river that joins the Brahmaputra.

The rapid shrinking, thinning and receding of the Himalayan glaciers due to rising temperatures and sudden rainfalls caused by global warming pose a real threat to the millions who depend on these rivers for sustenance.

Analysis

Scientists have analysed nearly 20 years of satellite images, and have come to the conclusion that the glaciers that flank the Himalayas and other high mountains in Asia are moving slower over time. They show that the ice streams which have decelerated the most are the ones that have also thinned the most.

The study is being presented at the American Geophysical Union (AGU) meeting in Washington DC, the world's largest annual gathering of Earth and space scientists. Led by the US space agency (Nasa), the assessment draws on one million pairs of pictures acquired by the Landsat-7 spacecraft between 2000 and 2017.

Automated software was used to track surface features on glaciers in 11 areas of High Mountain Asia, from Pamir and Hindu Kush in the West to Nyainqêntanglha and inner Tibet and China in the East. As the markers were observed to shift downslope, they revealed the changing speed of the ice streams. The research team, headed by Dr. Amaury Dehecq from Nasa's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, says nine of the surveyed regions show a sustained slowdown during the study period.

Nyainqêntanglha, for example, has seen a 37% reduction in speed per decade. For Spiti Lahaul, it is 34% - equivalent to about -5m/year per decade. These are glaciers that would normally move at tens of metres per year. The major revelation is that the reduction in velocity is strongly correlated with thinning. Nyainqêntanglha's glaciers have been thinning on average by about 60cm a year; Spiti Lahaul's glaciers are losing thickness at a rate of roughly 40cm a year. The slowdown trend is strongest in the south and southeast of High Mountain Asia; it is less pronounced in the West.

Counterpoint

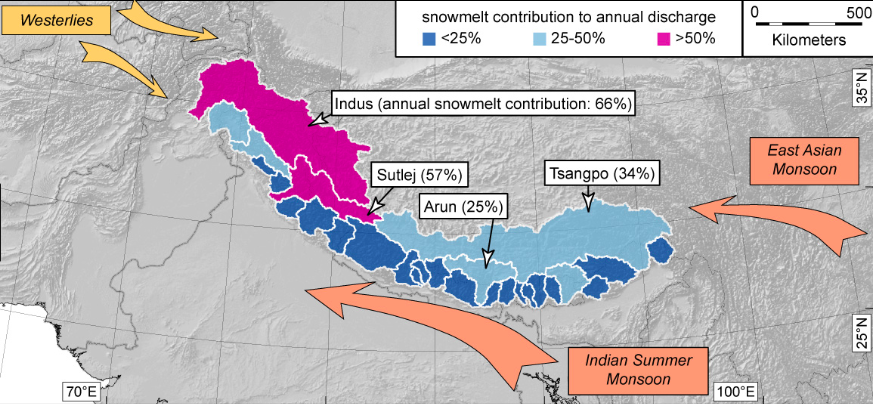

Regions like the Karakorum in Pakistan, and Kunlun just across the border in Tibet/China, have actually shown a slight thickening over time and a marginal speed-up as a consequence. This is due to the influence of different climatic conditions, as precipitation in the East is affected by the Asian monsoon and in the West and North-West, it is delivered by westerlies; it remains unclear exactly why the Karakorum has been gaining mass.

Assessment

Our assessment is that the loss of glacier ice could lead to water shortages, sudden changes in climatic conditions affecting agriculture, and problems of food and water security, which would create conditions that lead to tensions affecting several countries that share complex borders and trans-border eco-systems. We believe that a migrant crisis scenario could arise if there is damage to the glaciers and eco-systems of the Hindu-Kush Himalayan region or other disasters with high impact on livelihoods.

Comments