Having Second Thoughts?

August 12, 2023 | Expert Insights

Italy publicly announced its decision to withdraw from China’s Belt and Road (BRI) Initiative, what its newly elected prime minister called a “Big Mistake.” Italy joined the BRI in 2019, becoming the first major Western power and the only G7 member to do so.

Italy’s second thoughts about the BRI reflect Europe’s mixed approach and increasing caution towards China’s global infrastructure and connectivity project.

While the poorer Eastern and Southern Europe have been more open to BRI, Northern European countries have always been sceptical and suspicious of Chinese intentions. With theWith the sharpening U.S.-China cold war and China's role in the ongoing war in Ukraine, hob-knobbing with Beijing is no longer fashionable in Europe. That Rome has been the first to take the plunge in veering away from China, despite the bonhomie with Beijing that was very much on show during the pandemic devastation in Italy, is by itself significant.

Background

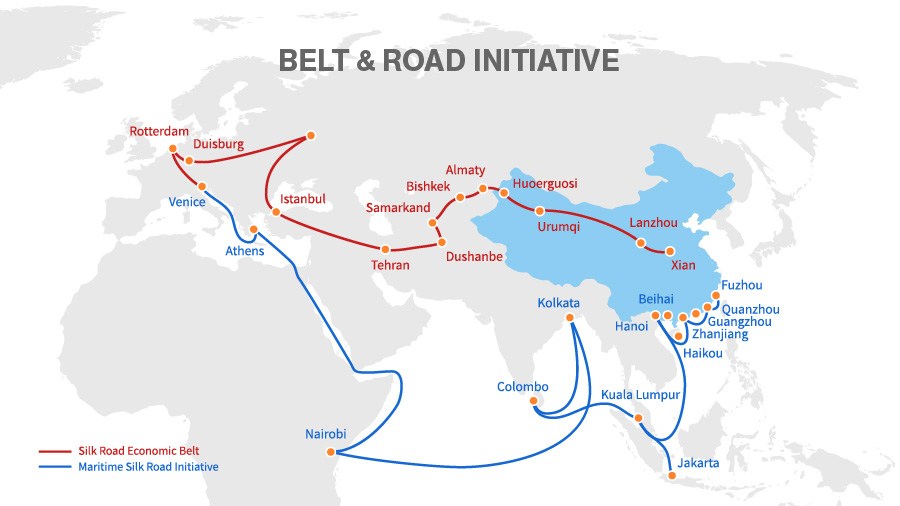

President Xi Jinping launched the BRI in 2013 to enable exchange between China, Eurasia, and Africa through a network linking railway lines, airports, and shipping routes. The BRI revives the concept of the ancient Silk Road linking trading centres of China, Asia, and Europe. The BRI includes rail, road, sea, airport infrastructure, power and water infrastructure, real estate contracts, and even digital infrastructure in recent times.

These projects involve increased cooperation between China and European states in institutionalised, contractual, and structured ways. Europe is a major destination for Chinese investment and trade. Almost all European countries have entered into some kind of formal cooperation with China under the ambit of the BRI. While some have formal BRI endorsements, others have contractual arrangements. These include infrastructure cooperation (based on investment), financial cooperation (joint investment), and education and health projects. This complex network of different levels of cooperation has enabled China to increase its influence and connectivity in Europe.

While Eastern European countries tend to have the highest level of cooperation as official BRI members, North-West Europe has varying levels of cooperation. In addition, countries like Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Finland are involved in specific infrastructure projects such as the Budapest-Belgrade railway line or the Peljesac-Bridge in Croatia. Further, the massive China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO) has acquired stakes in several major European ports. It also runs and owns certain ports, such as the strategically located Piraeus harbour in Greece. While Spain has not entered into a formal Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) or contract, COSCO has invested in Spanish harbour companies and cooperates with them over specific ports. Like many South European countries, Spain has shown an inclination to actively participate in the BRI.

Countries like Austria, Czechia, Luxembourg, the United Kingdom, and Switzerland are involved in financial cooperation with China, where they invest in domestic projects and projects in other countries with BRI involvement.

When Italy joined BRI as a member, it sought to revive its economy by attracting investment and increasing exports. For China, Italy was a prime gateway to Europe, but its membership was also culturally significant for the BRI narrative, which emphasises historical connections across Asia and Europe based on the ancient Silk Route.

Analysis

Most countries in Central and Eastern Europe are members of the BRI. These countries' political response and regulatory environment are generally more favourable to the BRI than Western Europe. They also have greater infrastructure needs, and financing is often a major obstacle. When the euro crisis struck, many hard-hit countries turned to China as they had to privatise national assets, including strategic infrastructure. China's investment in the Piraeus port is a leading example of this. Much to Brussel's concern, China has set up a 17+1 cooperation framework with Central and Eastern European countries. These arrangements have increased China's political influence over countries such as Greece and Hungary.

On the other hand, North and West Europe countries like Germany, France, and the UK are more sceptical of the BRI and concerned about China’s global expansionist tendencies. When Italy signed a BRI MOU, becoming the first G7 and NATO member to do so, many Western governments were concerned. Within the EU, it seemed like Italy had switched to the pro-China side of Europe.

Besides concerns about Chinese hegemony, many European countries are also concerned about BRI's divergence from international rules (such as EU or WTO law), which it substitutes with Chinese dispute resolution processes. Irrespective of whether or not China intends to establish a new global order, this factor has practical and legal consequences for European businesses and governments.

Other concerns include the BRI's lack of regard for labour, environment, and human rights standards, its lack of transparency, and the unsustainable debt it creates. An instance of China's debt-trap diplomacy is its highway project in Montenegro in East Europe, which left the country knee-deep in debt. There are concerns about China gaining control over strategic infrastructure like airports and telecommunications systems that could enable cybercrime and espionage. Further, the BRI seems to divert trade flows toward China without creating reciprocal market access for European exports. The EU is also keen to reduce its dependence on China to minimise its exposure to economic risk.

The BRI made substantial progress until 2018, when difficult economic conditions in borrower nations, unsustainably escalating BRI debts, and slowing economic growth led China to scale back the initiative. The COVID pandemic in 2019 largely halted BRI infrastructure projects. In 2021, investment in European BRI countries declined by 84% compared to the first six months of 2020. In 2022, Russia's invasion of Ukraine and China's support for Moscow exacerbated tensions between Europe and China. Italy's second thoughts about the BRI reflect growing Western caution towards China in the light of Taiwan, Ukraine, and China's growing global influence.

Assessment

- China has established BRI cooperation arrangements across Europe and gained entry into Europe through strategically located links. However, the BRI in Europe has declined in recent years, particularly due to China's slowing economic growth and Europe's heightened suspicion of China. This trend will only get stronger as China’s economic heft wilts.

- Italy’s second thoughts on the BRI are significant in the new global geopolitical context, which reflects a growing polarisation between several Western nations on one side and China and Russia on the other side.

- This is good news for India as it enhances opportunities for Indian investments and trade in the region. It also vindicates India's stand in South Asia, where BRI projects have been geopolitically isolating India from its immediate neighbours and, apart from benefiting only the Chinese investors and private companies, putting the smaller countries deeper into Chinese debt. Sri Lanka and Pakistan are the best examples.

Comments