“Flesh-eating” disease in Australia

April 17, 2018 | Expert Insights

The Medical Journal of Australia has called for an “urgent scientific response” to Buruli ulcer, an “epidemic” endangering certain regions in Australia. Buruli ulcer is caused by a bacteria that produces a flesh-eating toxin. Reports of Buruli ulcer have increased in Australia in recent years. Doctors have not yet discerned how this disease is transmitted.

Background

Infectious diseases are a broad group of diseases often spread by microscopic organisms such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, or parasites. These pathogens are transmitted through various means, such as person-to-person direct or indirect contact, through infected food or water, or vectors such as rats, lice, and mosquitoes. Infectious diseases such as Malaria, Tuberculosis, Dengue, Ebola, and HIV/AIDS account for a large proportion of human deaths. According to WHO, in 2002, infectious diseases were responsible for 22% of all deaths and 27% of disability adjusted life years worldwide.

Minimising the transmission of infectious diseases has always been an important part of healthcare services. Immunization through vaccinations, screening for diseases, and educating those in risk of infection are strategies used to prevent the spread of these diseases. Historically, globalization has played an undeniable role in the spread of diseases between countries or regions. As goods and people began to traverse continents, they brought disease with them, from smallpox, to the West Nile Virus, or HIV. However, globalisation has also created opportunities to address the spread of disease. In recent years, international efforts have helped curb deaths caused by diseases such as AIDS and malaria.

Buruli ulcer

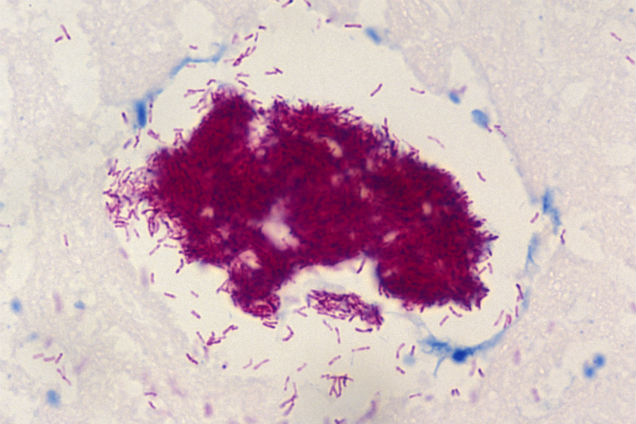

The Buruli ulcer is an infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium ulcerans. The name Buruli comes from a region in Uganda where the disease was studied. Mycobacterium is the same family of bacteria that causes other infectious diseases such as leprosy and tuberculosis. It is yet unknown how M. ulcerans is transferred to humans. Mycobacterium ulcerans flourishes in tropical conditions (29-33 degrees) and needs only 2.5% concentration of oxygen. It is highly endemic, and generally linked to water.

M. ulcerans produces a toxin called mycolactone, which damages tissues, skin cells, blood vessels, and fat, leading to the formation of ulcers. The toxin also prevents an immune response. Initial symptoms of infection include swelling and induration. If undiagnosed, an ulcer forms within 4 weeks. Severe cases can result in permanent disfiguration and bone deformities, however, it is generally not fatal.

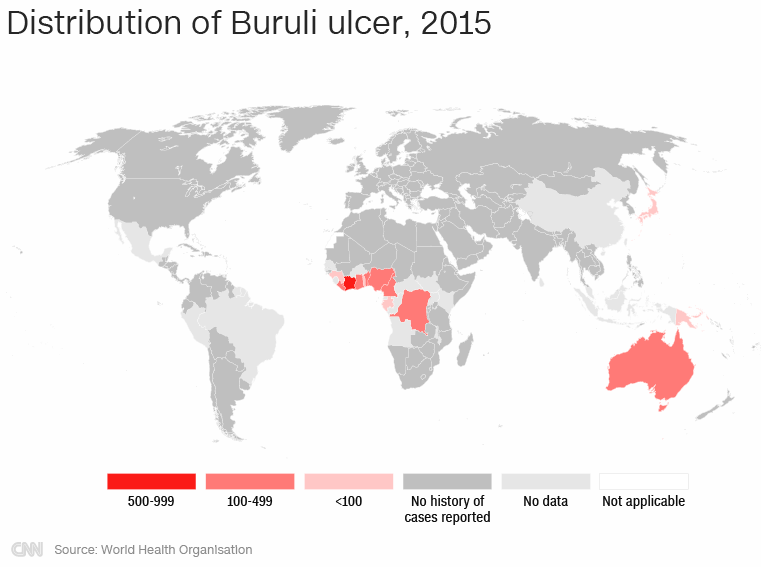

Buruli ulcer has been identified in 33 countries across the world in Africa, the Americas, Asia, and the Western Pacific. A large majority of the cases are from West Africa, including Benin, Cameroon, Ivory Coast, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Ghana. In these regions, it is prevalent in marshy and swampy terrains with slow-flowing water. Other countries with a significant number of cases include Australia and Japan.

Analysis

On Monday, the Medical Journal of Australia published a report on Buruli ulcer, warning that the disease is an “epidemic” that has “reached frightening proportions”. Incidences of the disease have reportedly increased by 400% in the last four years.

In Australia, the Buruli ulcer is also called the Bairnsdale ulcer or Daintree ulcer. The disease was first identified in Australia in the 1930s. A large proportion of cases in Australia are reported from the south-eastern state of Victoria. “Here, the community is facing a worsening epidemic, defined by cases rapidly increasing in number, becoming more severe in nature, and occurring in new geographic areas,” the report noted.

Outbreaks of the disease have been linked to environmental factors such as contact with contaminated water or flooding. Additionally, "Lesions most commonly occur on exposed body areas, suggesting that bites, environmental contamination or trauma may play a role in infection, and that clothing may protect against disease." It has been speculated that insects such as mosquitoes and animals such as possums are carriers of the disease.

The lack of knowledge on the mode of transmission is a major limitation. The report notes, “Efforts to control the disease have been severely hampered because the environmental reservoir and mode of transmission to humans remain unknown.” Buruli ulcer also affects animals such as koalas, possums, dogs, and cats. The WHO has pointed out that international travel can cause the disease to spread to non-endemic areas. “It is therefore important that health workers are knowledgeable about Buruli ulcer and its clinical presentations,” the agency warned.

While there are currently no means of prevention of the disease, cure rates are almost 100%. The disease is treated by antibiotics such as rifampicin and clarithromycin. Disability prevention and rehabilitation are an important part of treatment. However, studies have noted that the disease is not covered by benefit schemes; additionally, it can result in a need for plastic surgery. Therefore, total treatment can cost up to $ 14,000 per person. According to the WHO, current research on the disease is focussed on the development of oral antibiotic treatment, rapid diagnostic tests, and determining the mode of transmission.

Assessment

Our assessment is that while Buruli ulcer is largely endemic, it is essential to check the spread of this disease in order to prevent a wider outbreak. In a globalised world, diseases travel rapidly across boundaries and it would be wise to check this disease while it is relatively contained. We believe that research investigating the transmission of the pathogen, would help health authorities delineate preventive measures and contain the disease.

Comments