EU Fights Election-Time Fake News

December 7, 2018 | Expert Insights

European Union authorities want internet companies including Google, Facebook and Twitter to file monthly reports on their progress eradicating "fake news" campaigns from their platforms ahead of elections in 2019.

Background

The European Parliament is the directly elected parliamentary institution of the European Union. Together with the Council of the European Union and the European Commission, it exercises the legislative function of the EU. The next Elections to the European Parliament are expected to be held in 23–26 May 2019. A total of 751 Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) currently represent some 500 million people from 28-member states. In February 2018, the European Parliament voted to decrease the number of MEPs from 751 to 705, after the United Kingdom withdraws from the European Union on the current schedule.

Foreign electoral interventions are attempts by governments, covertly or overtly, to influence elections in another country, as a means to accomplish regime change abroad. The most recent instance was in October 2016, when the U.S. government accused Russia of interfering in the 2016 United States elections using a number of strategies including the hacking of the Democratic National Committee (DNC) and leaking its documents to WikiLeaks, which then leaked them to the media. Several Russians were accused of using social media to garner support for US President Donald Trump. Russian agents were also accused of spreading "fake news" via social media platforms to influence the election result.

The Code of Practice on Disinformation was created by the European Commission in April 2018; representatives of online platforms, leading social networks, advertisers and advertising industry agreed on the self-regulatory Code of Practice to address the spread of online disinformation and fake news. The Code aims at achieving the objectives set out by the Commission's Communication presented in 2018 by setting a wide range of commitments, from transparency in political advertising to the closure of fake accounts and demonetisation of purveyors of disinformation.

Analysis

Five months ahead of the European elections in May 2019, the EU's executive has proposed more than doubling the Commission's budget to tackle disinformation from €1.9 million ($2.1 million) to €5 million.

"Disinformation is part of Russia's military doctrine and its strategy to divide and weaken the West. We have seen attempts to interfere in elections and referenda, with evidence pointing to Russia as a primary source of these campaigns,” Andrus Ansip, the EU's vice president for the digital single market said. Russia spent €1.1 billion each year on pro-Kremlin media according to Ansip, a former prime minister of Estonia.

The extra EU funds will mean more staff and equipment in Brussels and among EU delegations, so that data and analysis on propaganda campaigns can be shared among EU member states. A "rapid alert" mechanism would warn governments to fend off developing disinformation campaigns.

The Commission called on Facebook, Google, Twitter, Mozilla and advertising trade associations to "swiftly and effectively" act on disinformation by closing fake accounts and blocking messages spread automatically by bots.

The Commission's Justice Commissioner, Vera Jourova, said the EU would pressure online giants to fulfil their commitments with "regulatory" action should they not live up to the Code of Practice they signed. "We are facing a digital arms race and Europe should not stay idle," Jourova added.

Facebook has a "war room" against misinformation and manipulation by foreign actors trying to influence elections worldwide. This came in response to accusations that it did too little to prevent Russian misinformation efforts during the 2016 US presidential election. The Commission's plan still has to be approved by EU leaders. If it gets the go-ahead, the system could be up and running in March.

Counterpoint

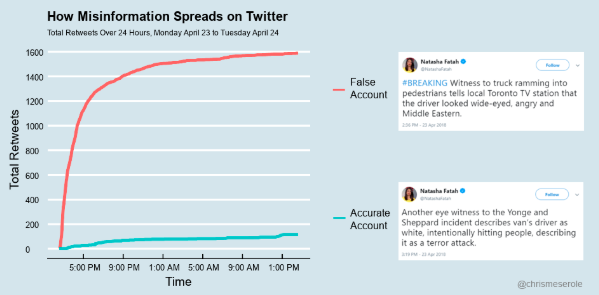

While it is essential to curtail the spread of misinformation, the lines between curbing fake news and internet censorship can become blurred. During a fake news “attack”, social media platforms could promote police accounts so that accurate information is disseminated as quickly as possible. Alternately, it could also display a warning at the top of its search and trending feeds about the unreliability of certain accounts.

Assessment

Our assessment is that just as the problem of fake news has both a human and technical side, so too does any potential solution. We believe that the solution to misinformation will also need to involve the users themselves; not only do social media users need to better understand their own biases, but journalists in particular need to better understand how their mistakes can be exploited.

India Watch

The weaponization of social media platforms like WhatsApp to spread fake news have gathered momentum in India, especially during election years. The number of countries that witness cyber-troop activists, which are formally organised social media-manipulation campaigns by a government or political party, has already risen to 48 from 28 in 2018, shows a study on computational propaganda (pdf) by Oxford University researchers. In India, like in the 48 other countries included in the study, cyber-troop activity is especially tied to elections. The researchers found evidence of political parties spreading propaganda on social networks during elections or referenda.

Comments