The Enforcement Predicament

June 2, 2021 | Expert Insights

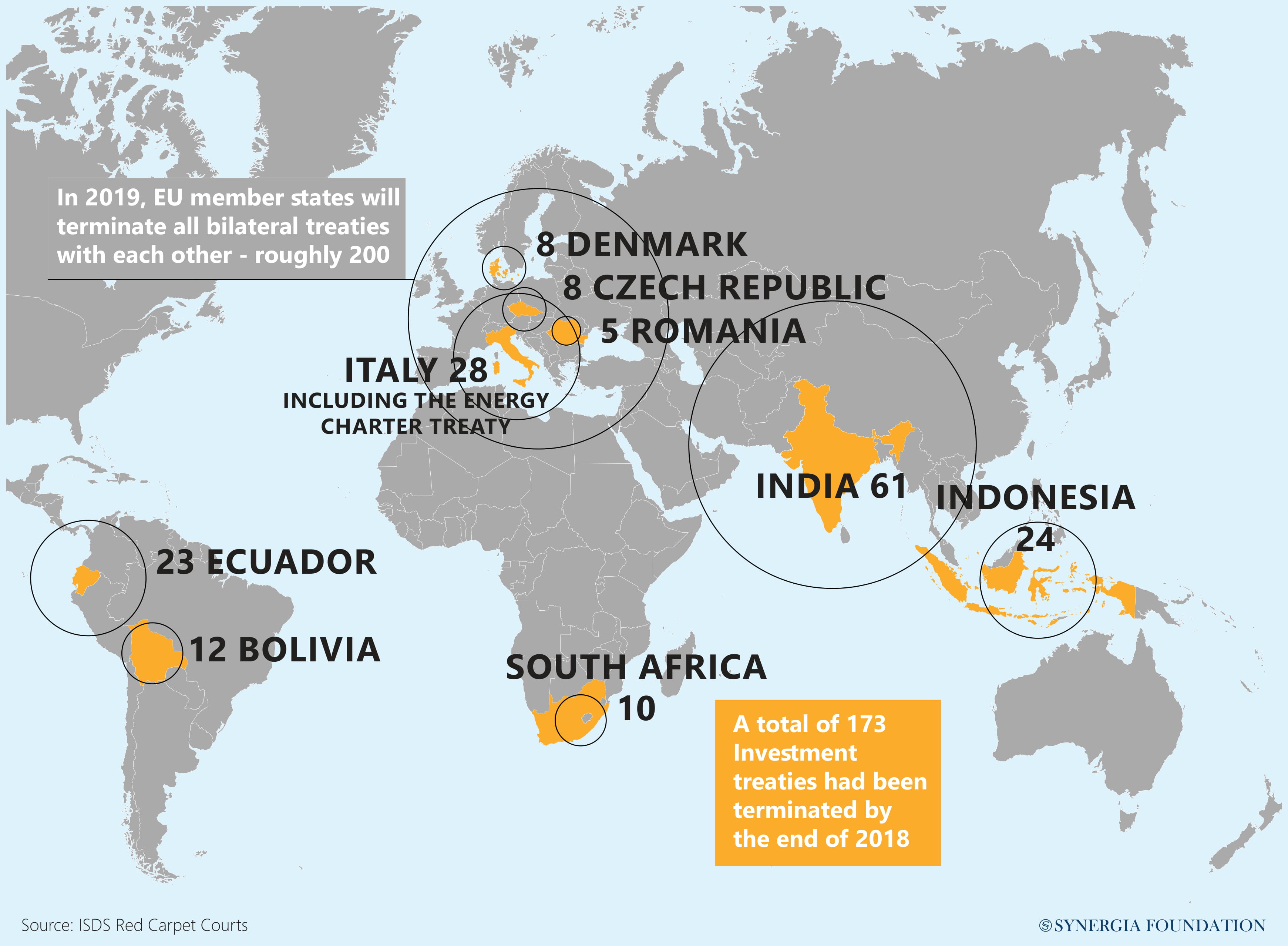

In India, the enforcement of arbitral awards under an investment treaty remains legally murky.

CLARIFYING THE ENFORCEMENT TERMS

Under ordinary circumstances, after securing an investment award in its favour, a company would seek to enforce the same in a jurisdiction where the respondent state has maximum assets. In the Cairn arbitration case, therefore, the natural choice would have been India. However, the country’s high courts have adopted conflicting positions about the applicability of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act 1996 (Arbitration Act) to investment treaty awards, thereby raising doubts about their enforceability. For example, in Board of Trustees of the Port of Kolkata v. Louis Dreyfus Armatures, the Calcutta High Court seems to have operated under the presumption that investment awards are enforceable under the Arbitration Act. However, in Union of India v. Khaitan Holdings (Mauritius) and Union of India v. Vodafone Group plc, the Delhi High Court has remarked that arbitral awards under an investment agreement are not in the nature of commercial awards and therefore, should ordinarily be governed by a regime that is different from the Indian arbitration act. While this might have been in the nature of ‘obiter’, it still leaves a big vacuum for foreign investors, in terms of enforcing the awards that are granted in their favour. Given this legal uncertainty, India will need to clarify its position. Until the Supreme Court adjudicates on this issue, the Parliament should bring in a legislative amendment that clarifies the import of the Arbitration Act and its applicability to foreign investment awards. In fact, there are many who argue that investment treaties are not strictly outside the commercial regime, given that their premise is somewhat similar.

TREATY LANGUAGE

In both the Vodafone and Cairn cases, the government had contested the arbitrability of tax disputes. While resolving such admissibility and enforcement matters, the simple solution is to defer to the language of the treaty. If nothing indicates that India had agreed to exclude tax-related matters or taxation measures from the scope of its Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT), then an investor would be justified in resorting to arbitration or other mechanisms of dispute resolution, as provided under its ambit. For example, while the India- Russia BIT has completely excluded taxation matters, the India-UK BIT has made a mention of tax in the context of the ‘Most Favoured Nation’ status.

TREATY VIS-À-VIS PUBLIC POLICY

Lastly, the question of public policy is critical. India has the undeniable right to tax private parties, whether retrospectively or not. India has the undeniable right to tax private parties, whether retrospectively or not. Sometimes, it ends up reversing the effect of an SC judgement, as was seen in the Vodafone case, which left the investor feeling cheated. Treaty regimes embody a guarantee by the country that it has willingly decided to undertake the conditions accompanying them. On occasions, where a government decides to not have treaties, and an arbitral tribunal gives a decision against it, the country can question the ruling on the grounds of public policy.

Shwetha Bidhuri, is the South Asia head at the Singapore International Arbitration Centre. This article is based on her views shared at the 102nd Synergia Forum on ‘Retrospective Tax Law and India’s Global Road Ahead’.

Comments