Economic crisis in Zimbabwe

October 18, 2018 | Expert Insights

After enduring through hyperinflation and economic crisis in 2008, Zimbabwe is yet again facing the fear of another round of hyperinflation as people ration basic necessities like bottled water and even beers.

Background

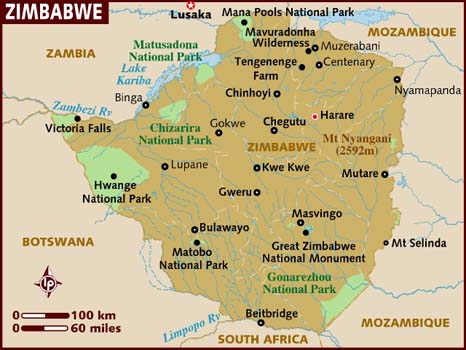

Zimbabwe is a landlocked country located in southern Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa, Botswana, Zambia and Mozambique. The capital and largest city are Harare. A country of roughly 16 million people, it is classified as a middle-income country, with a low HDI score and high-income disparity.

The Zimbabwean economy has been shrinking from the year 2000. The country has since been a desperate situation due to widespread poverty and massive unemployment. The country’s participation in 1998 to 2002 in the war in the Democratic Republic of the Congo led to the economy’s deterioration. The war drained hundreds of millions of dollars that eventually resulted in hyperinflation in the country.

Hyperinflation was a significant problem from about 2003 to April 2009, when the country suspended its own currency. Zimbabwe faced 231 million per cent peak hyperinflation in 2008. A combination of the abandonment of the Zimbabwe dollar and a government of national unity in 2009 also resulted in a period of positive economic growth for the first time in a decade.

During the height of inflation from 2008 to 2009, it was difficult to measure Zimbabwe's hyperinflation because the government of Zimbabwe stopped filing official inflation statistics. However, Zimbabwe's peak month of inflation is estimated at 79.6 billion per cent in mid-November 2008.

In 2009, Zimbabwe stopped printing its currency, with currencies from other countries being used. In mid-2015, Zimbabwe announced plans to completely switch to the United States dollar by the end of 2015.

Analysis

The economic crisis in Zimbabwe has shifted from bad to worse. The currency has collapsed, the unemployment rate has reached 90 per cent, and shops shelves have been stripped bare due to panic-buying.

The new crisis began when Mthuli Ncube, Zimbabwe’s finance minister, said he was dividing bank accounts into two types. One that contains “good” and “bad” dollars. The “good” accounts are those backed by real flows of dollars, remitted by millions of Zimbabweans in the diaspora. On the other, the “bad” accounts represent those holding electronic money, known as RTGS, or real-time.

Post the hyperinflation meltdown in the country over a decade ago, Zimbabwe has been dollarized. However, the people of the country have lost faith in the two surrogate currencies. In reality, neither of the two currencies trade at anything like parity. In the previous week, bond notes were worth as little as 20 cents on the dollar.

The newly elected government’s measures have resulted in the present economic spiral in the country. The country is facing foreign-exchange shortages and austerity measures that have left consumers facing long queues for everything from fuel to bread, sugar and cooking oil. Many shops are under pressure from the government as they are restricting customers’ purchases to prevent hoarding and ensure everyone gets something. Others have gone further: Yum! Brands temporarily shut some of its KFC outlets this week, saying it couldn’t find enough dollars to pay suppliers. The government also introduced new measures last week that has imposed a tax increase on money transfers. As a result, it triggered a rise in primary commodity prices, fuelling fears of an inflationary spiral and also long queues at gas stations.

John Robertson, a local economist, said the Zimbabwean state had wiped out savings before, a reference to the hyperinflation of 2007 and 2008. “This cost people so much that trust in government pronouncements no longer exists.”

Tendai Biti, an opposition leader, told the BBC that the new finance minister would not be able to fix an economic crisis born of years of reckless mismanagement. “You can rig an election, but you cannot rig an economy,” he said.

Counterpoint

Finance Minister Mthuli Ncube had previously stated that “Bold decisions need to be taken on the reforms front to stimulate growth and sustainable development.” He also stated that reforms in the nation are inevitable, and so are its consequences. “The liberalisation of the economy has its pains, and this is one of the pains that we are going to go through,” he said.

Besides, though the government was lauded for finding the root cause of the financial problem in the nation, the ministry’s attempts to end parallel currency system has triggered rumours that the administration is preparing to wipe out savings through devaluation.

Assessment

Our assessment is that contradictory statements about how the government plans to navigate the currency crisis, a new two per cent tax on electronic transactions and heavy-handed approach to managing the fallout have bred suspicion and a fundamental lack of confidence in the government.

Comments