Demonitisation, Two Years On

November 9, 2018 | Expert Insights

8 November marks the second year since India demonetised all ₹500 and ₹1000 banknotes. Small and medium businesses are still struggling to recover from the impact of the policy.

Background

On 8 November 2016, the Government of India announced the demonetisation of all ₹500 and ₹1000 banknotes of the Mahatma Gandhi Series. It also announced the issuance of new ₹500 and ₹2000 banknotes in exchange for the demonetised banknotes. The government claimed that the action would curtail the shadow economy and reduce the use of illicit and counterfeit cash to fund illegal activity and terrorism.

The announcement of demonetisation was followed by prolonged cash shortages in the weeks that followed, which created significant disruption throughout the economy. Several deaths were linked to the rush to exchange cash. Initially, the move received support from several bankers as well as from some international commentators. In some quarters, the move was criticised as poorly planned and unfair and was met with protests, litigation, and strikes against the government in several places across India.

Analysis

November 8, 2018, is the second anniversary of India's demonetisation.

Three main objectives were laid down on the day the policy of demonetisation of ₹500 and ₹1,000 currency notes was announced. The first was to "break the back" of corruption and black money, the second to end the circulation of fake currency and finally to end terrorist financing. The gazette notification outlined the same three objectives but did not mention corruption.

The main objective of demonetisation of the HDNs of ₹500 and ₹1,000 notes which took out 86 per cent of the currency in the market was ending the scourge of black money. In late 2016, the attorney general told the Supreme Court that the government expected a quarter to a third of the HDNs in circulation not to return to the banking system, implying this would be the amount of black money destroyed by removing it from circulation.

Two years later the actual picture emerged: The RBI Annual Report for 2017-18 said that 99.2 per cent of the ₹15,440.5 billion of the HDNs in circulation on 8 November 2016 returned from circulation.

There was indeed a spike of fake high denomination notes of ₹500 and ₹1,000 detected during the surrender of notes in late 2016. However, since the new series of currency notes did not have any additional unique security features, the counterfeit presses were soon in operation: a small number of fake notes of the new ₹2,000 were detected in the last few months of 2016-17 itself and a much larger number (almost 18,000 pieces) in the next year, 2017-18.

Disaffection, as expressed in terrorism in the two years since November 2016, has been no less than before.

Two years on, the economy and its institutions continue to experience the negative after-effects of the processes and the events surrounding demonetisation. For instance, the central government has put pressure on the Reserve Bank of India and its governor, Urjit Patel, to hand over its surpluses only because two years ago the RBI under the same governor did not demur on the demonetisation of 2016. Former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh said that besides the steep drop in the economic growth rate, the deeper ramifications of the currency ban were still unravelling and that small and medium business, the cornerstone of India’s economy, were yet to recover from the demonetisation shock. “It is, therefore, prudent to not resort to further unorthodox, short-term economic measures that can cause any more uncertainty in the economy and financial markets. I urge the government to restore certainty and visibility in economic policies,” said Singh’s statement tweeted by the Congress party.

The opposition party’s warning comes in the wake of reports that the government may invoke the never before used Section 7 of the RBI Act to issue directions to the central bank. Media reports also suggested that the government was seeking transfer of Rs 3.6 lakh crore, more than a third of the reserves of the central bank, to the government.

“Today is a day to remember how economic misadventures can roil the nation for a long time and understand that economic policymaking should be handled with thought and care,” said the statement from Singh. It also said demonetisation had a direct impact on employment as the economy continues to struggle to create enough new jobs.

Counterpoint

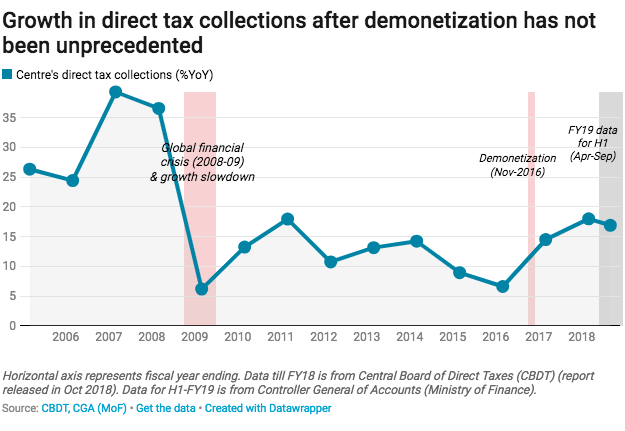

Finance minister Arun Jaitley said that the November 2016 demonetisation was a key step in a chain of decisions taken to formalise the economy, which had increased the number of taxpayers and made evasion more difficult. While the growth in direct tax collection after demonetisation was not unusual, it has undeniably sped up the process of digitising the economy by enabling Indian payment portals like PayTM to flourish.

Assessment

Our assessment is that the demonetisation policy did not ultimately achieve the objectives that it set out to accomplish. However, we believe that it set a dangerous precedent by allowing the government to freely intervene in monetary policy, which has traditionally been under the sole authority of the Reserve Bank of India.

Comments