Defeating Ebola, Finally?

January 21, 2023 | Expert Insights

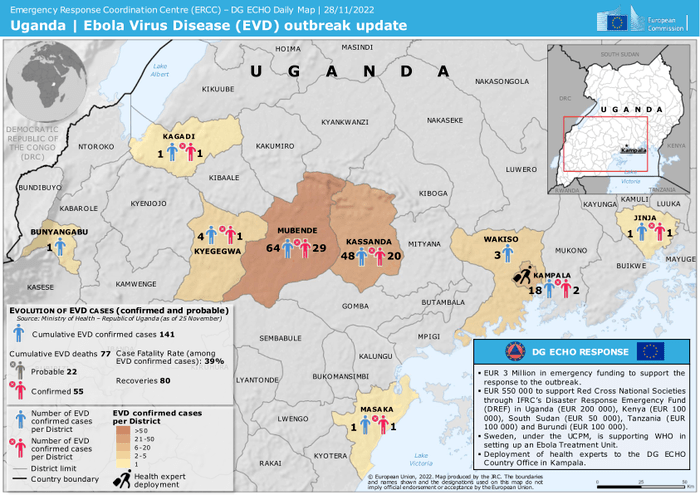

Uganda recently declared the end of the Ebola disease outbreak caused by the Sudan species of the Ebola virus. The victory was declared less than four months after the first case was confirmed in its central Mubende district in the most recent outbreak of September 2022. This was Uganda's fifth Ebola virus outbreak since the Ebola epidemic first appeared in 2013. This time the overall case-fatality ratio was 47 per cent, with 55 deaths, the lowest in the country's history.

Deservedly, Uganda has come in for a great deal of global approbation, considering that the results were achieved mostly locally. As per the government, Uganda, a long-time sufferer of the scrouge of Ebola, a most disgusting and lethal affliction, mounted a robust and comprehensive response this time around, mobilizing, synchronizing, and reorienting its entire health system and infrastructure. The entire gamut included having an alert system, contacts tracing and caring for infected people and their contacts and gaining affected communities' full participation in the response.

Background

Named after a river in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where the first outbreak was recorded, the Ebola viral haemorrhagic disease is one of the most prominent causes for worry among the public health officials of African nations, where it has majorly occurred. The 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa started in a rural setting of south-eastern Guinea, spread to urban areas and across borders within weeks, and became a global epidemic within months.

Uganda has already experienced four Ebola Virus Disease outbreaks in 2000, 2014, 2017 and 2018, before having the 2022 breakout with other cases of Marburg, Crimean Congo Haemorrhagic fever, Yellow Fever, Rift Valley Fever, Avian Influenza and measles in between. Despite being riddled with intermittent violent conflicts, military coups, authoritarian regimes, economic stagnation and refugee influx since independence, the country has successfully used its high disease burden to strengthen the epidemic preparedness and response team in addition to adequately investing in health infrastructure, capacities and robust institutional- community relationships.

Analysis

The recent Ebola outbreak in Uganda being caused by the Sudan species has made it one of the most challenging flare-ups, according to the WHO statement. This was especially so because all the existing vaccines or therapeutic options at the time of the flare-up only worked for the Zaire strain of the virus, which is roughly 40 per cent genetically different from the Sudan strain.

Although Uganda did not use any vaccine to contain the Ebola outbreak, it managed to tide over the crisis by virtue of its long experience in responding to epidemics. The mitigating strategy included strengthening critical areas of response and identifying specific factors contributing to the successful management of public health emergencies to overcome the lack of key immunization tools.

On the other hand, DRC tackled its Ebola flare-up by immediately deploying vaccines, though its overall response shares key similarities with that of Uganda. The DRC outbreak reported its last infection case in September 2022; fortunately, there have been no fresh cases since then.

A common feature in both Uganda and DRC was the rapid testing of suspected infection cases to provide Ebola-specific medication at the earliest, enhancing survival and stopping the spread of infection. Two other parallel measures adopted included using a mobile application for Ebola contact tracing and telemonitoring and embracing a hyper-contextualized approach in dealing with different affected communities instead of using a one size fits all approach.

Interestingly Uganda had three batches of candidate vaccines, provided by the WHO, ready for use in the recent Ebola outbreak in a record time of four months. The speed of this collaboration marks a milestone in the global capacity for responding to rapidly evolving outbreaks and preventing them from becoming larger.

This is very good news because the WHO, accused of its laggard response termed as a 'toxic cocktail' to the outbreak of COVID-19, seems to be getting its act together by expeditiously collaborating with impacted countries. WHO seems to have learnt a lesson after it burnt its fingers in delaying the announcement of the COVID outbreak in China as an international emergency or a pandemic at China's behest, resulting in a consequential delay of adopting appropriate measures by countries to halt the spread of the virus. The WHO was also hindered by its faulty advice that travel restrictions should be the last resort in handling the Covid pandemic. Moreover, it failed to stop the 'winner takes it all' scramble for protective equipment, medicines and vaccines that the world had descended into when Covid cases rose.

However, WHO’s guidelines have successfully improved and standardized supportive care and treatment for the symptoms of Ebola disease in Uganda, besides providing a comprehensive programme of follow-up care to tackle the complications of the Ebola survivors and track their health to prevent a re-emergence of the disease. This underscores WHO's will to learn from past mistakes and its multi-level relevance in aiding countries to counter disease breakouts in a sustained fashion.

Assessment

- The political commitment, implementation of accelerated and clearly defined public health actions, and heightened community awareness have proven to be the 'magic bullet' in Uganda's winning the vaccine-less war against the Ebola outbreak.

- The Covid pandemic has shown the ill effects of disease data secrecy, unplanned mitigation strategies and shying away from global collaboration. Uganda's victory, with WHO's support, involved a correction of all these missteps besides highlighting the importance of eking out an international partnership to tackle both curative and preventive aspects of outbreaks.

- Although the outbreak in Uganda has been declared over, the latter and its neighbouring countries, including South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, should continue monitoring their population, given the high transmission rates of the Ebola virus.

Comments