Deconstructing the Taiwanese Model

August 5, 2021 | Expert Insights

Mr. Premjith Krishnan is the Deputy Director at Taipei Computer Association. This article is based on his views at the 104th virtual forum on ‘Semiconductors and Supply Chains in Asia’, jointly organised by the Synergia Foundation and the Taiwan Center for Security Studies.

The escalating demand for semiconductors in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic has produced supply chain constraints, making this is an opportune time to explore collaboration between India and Taiwan. The increased adoption of technology across all sectors and regions has created a global market for chips, which is estimated to reach 522 billion dollars by the end of 2021. In fact, companies like the International Green Chip (IGC) expect a year-on-year growth of 12.5 per cent over the coming years. Predictably, therefore, the proliferation of new technologies and data services has shone the spotlight on the global foundry market.

GROWTH STORY

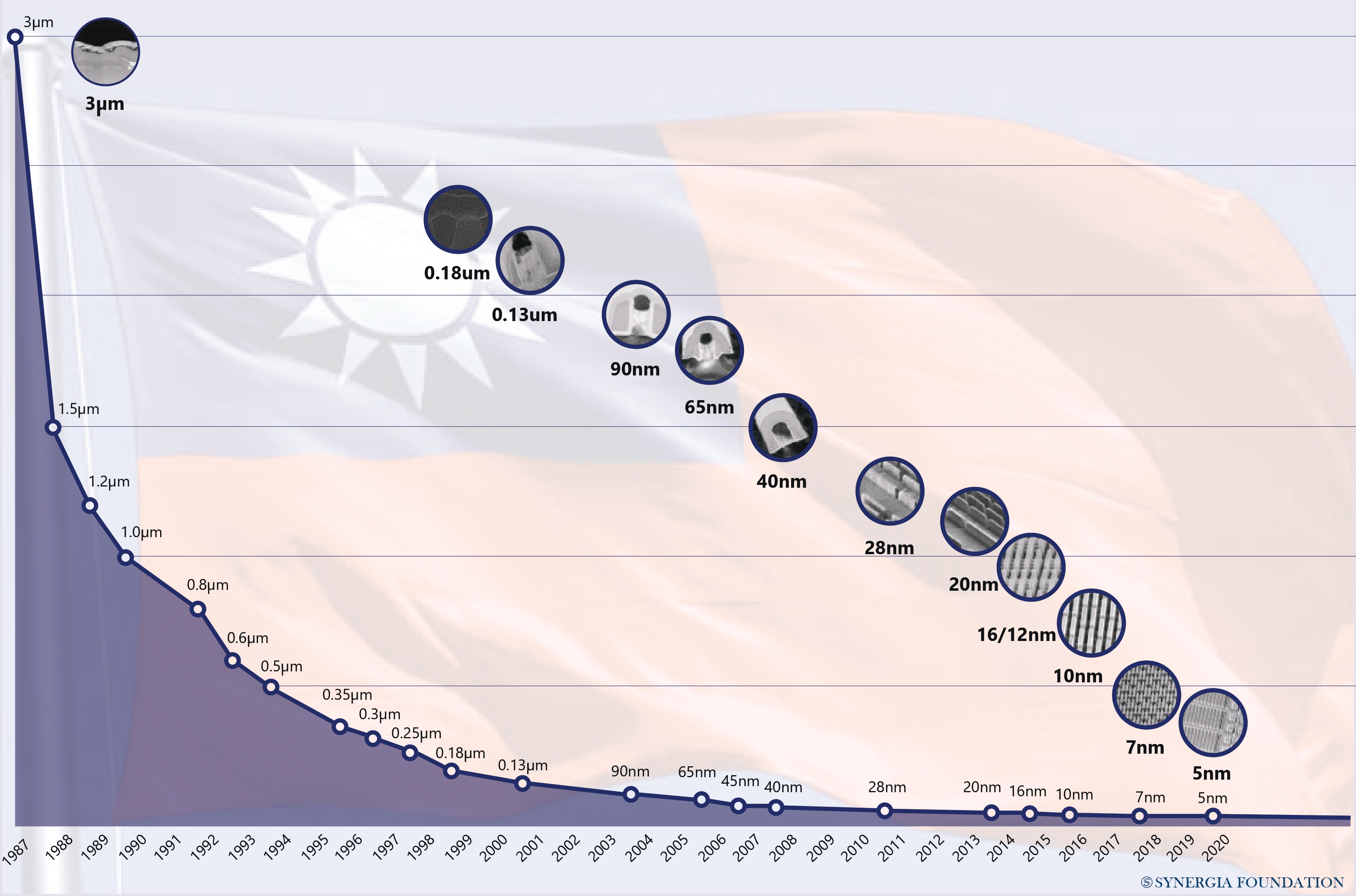

Currently, Taiwan dominates the outsourcing of chip manufacturing. Having begun its journey almost four decades back, the country’s path towards becoming the largest semiconductor supplier is truly remarkable.

Many of its entrepreneurs, who pursued their education and industrial experience abroad, deserve the credit for bringing this technology into the country and stimulating growth. The Taiwanese government, too, was proactive in implementing a unique set of policies at the right time. It not only helped to refine the capital market in the direction of equities, but also contributed substantial research and development (R&D) support for the Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI).

Now, the industry has reached such a stage that it comprises 238 fabless design companies, 37 packaging and testing companies, 15 fabrication companies, 11 wafer suppliers, seven substrate suppliers, three mask makers and four lead frame companies. Over the last year, its contract manufacturers together accounted for more than 60 per cent of the total global foundry revenue.

Much of this success has been attributed to the stellar performance of one firm, namely the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC). At present, TSMC garners almost 54 per cent of the total foundry revenue. As designers and manufacturers embark on a continuous quest to make chips smaller and smarter, TSMC has emerged as one of the primary foundries that can manufacture the most advanced chips. In fact, it is gearing up to produce next-generation 3nm chips, with reports suggesting that the process might commence as early as 2022.

A SUPPORTIVE ECOSYSTEM

In Taiwan, the entire semiconductor ecosystem is located well within a distance of a few hundred miles. The industrial cluster is characterised by a vertically disintegrated infrastructure, where different companies focus on particular areas of expertise, as opposed to mastering the entire supply chain. In fact, many of them are small and medium enterprises. Therefore, Taiwanese semiconductor suppliers will invest or move to a new market only if the bigger players along the supply chain decide to do.

Given that the fab is overly complex in terms of its technology as well as commercial operations, any shift to new geographies and ecosystems will not be easy. It requires huge investments that support business and operational abilities, while taking into account the high level of obsolescence in this industry.

As far as infrastructure planning is concerned, stable power and water supply are extremely critical. Apart from the availability of skilled labour, it is important to structure labour management practices when operating in different geographies and cultures. This needs to be accompanied by a strong and long-sustaining policy framework in host countries.

DIVERSIFY AND ADAPT

The supply chain bottlenecks triggered by the pandemic have compelled many countries to explore models of self-reliance in the semiconductor industry. Moreover, internal and external security threats are pushing Taiwanese chip companies to diversify their investments in other geographies and get closer to the market.

Against this backdrop, Taipei needs to think outside the box. Given that India is a leading powerhouse of chip design, there are tangible opportunities for cooperation. However, companies will need a helping hand from regulatory authorities and industry associations to adapt to new cultures and geographies. Joint ventures with Indian players or a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with organisations like the Indian Electronics and Semiconductor Association can go a long way in bridging these gaps.

Comments