David Versus Goliath Season 2

February 17, 2024 | Expert Insights

The Houthis have managed to raise the hackles of world powers with their targeted attacks in the critical waterway.

The Red Sea crisis, an offshoot of the relentless Israel-Hamas war, has captured global attention as the Houthis attack merchant ships in the critical sea lane.

The crisis graphically illustrates how small armed actors with the support of external state supporters can pose a significant threat to global powers.

Background

The Houthis, an armed rebel group controlling most of northern Yemen, have captured global attention with their drone and missile attacks on ships traversing a crucial strait leading to the Red Sea and the Suez Canal.

The Houthis claim the attacks are meant to pressure Israel to stop its war on Gaza. However, it is increasingly clear that they are also using the situation to gain leverage with global powers. For instance, Saudi Arabia subsequently offered more concessions in its negotiations with them over the Yemen conflict.

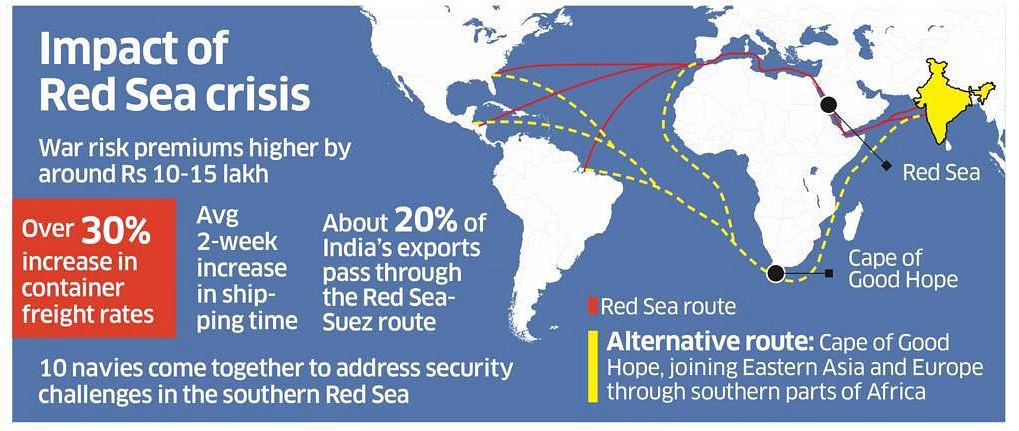

Their attacks have compelled merchant ships to reroute from the crucial route, significantly escalating shipping charges and insurance costs. This has impacted shipping companies, oil giants, and international trade. The economic fallout is inevitable: the narrow waterway witnesses 40 per cent of Asia-Europe trade, including vast energy supplies for Europe, food items, and most global manufactured products. Around 30 per cent of the world's container traffic and more than 1 million barrels of crude oil usually transit through the Suez Canal daily.

The Red Sea is also of geopolitical importance: many countries have military bases to protect oil and merchant ships. These include the United States, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, China, Italy, France, and Japan.

Analysis

The Red Sea crisis has brought to the fore a key security issue - small militant actors who pose a significant challenge to states and global powers. From the Taliban gaining control of Afghanistan in 2021 to the rise of the Houthis in Yemen, these militant actors are proving to be more formidable than expected.

Like Hamas in Gaza and Hezbollah in Lebanon, the Houthis are an Iran-backed militant outfit. Middle Eastern players like the Gulf countries are concerned about the conflict escalating into a regional conflict with Iran’s involvement. With the US-led task force effort to protect ships from the attacks, leading global powers are now involved in the issue.

Militant outfits in the region are emboldened by Iran’s vocal support for Palestinians and its proclaimed “Axis of Resistance”.

Iran-linked groups and other non-state actors in the region in countries like Syria, Lebanon and Iraq have benefitted from more easily available military technology. This is particularly true since Tehran decided to liberalise ballistic missile technology, drones, and other weapons of asymmetric warfare.

However, the growing abilities of small militant outfits are also a result of a general trend of an increasingly level playing field where these non-state actors can easily access military technology and cheap AI. Whether drones, missiles, cyber-attacks, or misinformation campaigns, decentralised warfare is increasingly possible.

Iran’s tactic of maintaining buffer groups across the region to fortify its strategy has created a challenge for regional states and the US. In an increasingly uncertain global order, small, armed actors are gaining more clout and strategic equity, particularly where political vacuums arise.

The traditional approach to these actors has been shaped by the U.S. "war on terror" since the 9/11 terror attacks, which primarily relied on military engagement, such as in Afghanistan and Iraq against Al Qaida. It is mirrored in Israel's war on Hamas.

However, these actors are difficult to rout with conventional approaches like bombing or military combat. Saudi Arabia and UAE tried to drive back the Houthi rebels to the mountains they came from after they took over Yemen's capital, but its shower of bombs didn’t work and led to a cycle of violence that ravaged Yemen’s cities and civilians. These groups are also harder to track since they are irregular fighters. Moreover, their smaller numbers make them more mobile. They possess few command and control centres or high-value assets like industries, communication hubs, power plants, etc. that can inflict an economic cost on their organisation.

The Houthis now pose a challenge not just for regional states and the U.S. but for powers across the world that depend on the Bab al-Mandab Strait for their trade. Controlling a sizable part of Yemen, they can act with relative impunity. As non-state actors, they can bypass governments' responsibilities, such as concerns about preserving national resources and public security. Yet, they also benefit from the implicit support and sponsorship of Iran; regional powers are treading carefully with the Houthis to avoid provoking conflict with Tehran.

Saudi Arabia is a key example because of its firsthand military engagement with the Houthis in the Yemen conflict. The oil kingdom has learned its lesson and is following a different approach, trying to broker a ceasefire and reach an agreement with them. It is also interested in de-escalating tensions with Tehran as a part of its broader effort to foster regional reconciliation and stability so it can diversify its oil-dependent economy. However, the Red Sea crisis has convoluted these efforts. Even as the U.S. and UK shoot down cheap Houthi drones threatening their naval platforms with million-dollar-a-piece missiles, the Saudi Kingdom and other regional nations are reluctant to join the US-led operation. They are fearful of inflaming regional tensions (such as the ongoing Yemen conflict) and provoking retaliation against themselves.

Assessment

- As military technology continues to become more widely accessible and easy to use, small armed actors become increasingly potent. This is starkly visible in the Red Sea Crisis, where the Houthis pose a worrying challenge to global powers with their missile and drone attacks on merchant ships.

- On the one hand, they benefit from Iran’s implicit backing as states are reluctant to provoke Tehran and escalate the Gaza conflict into wider proportions. On the other hand, they enjoy the benefits of not being answerable to any state and other advantages that non-state actors possess.

- The sudden expansion of the Indian Naval operations in the Eastern Indian Ocean is a sign of times when national security encompasses sea lanes far from its own shorelines. In a copycat fashion, Somalian piracy has received a fresh impetus, and India is the only major power in a position to deal with it. This trend could easily spread over global sea lanes of communication, too.

Comments