Coming Closer Despite Differences

July 1, 2023 | Expert Insights

Since its independence, India has always tried to find a role for itself in the international scheme of things. Even when it was a low-income nation dependent upon foreign donors, even for its basic requirements like food, it punched way above its weight in diplomacy.

The hallmark of Indian external policy has been a pronounced tilt towards strategic autonomy, labelled during the Cold War (sometimes derisively) as Non-Aligned. While India’s nonalignment may be questioned by the West, considering that almost our entire inventory or offensive weapons systems came from the USSR along with unstinted backing in the UNSC, overall, India desisted from throwing its weight with any particular bloc.

This path has not been easy, especially economically, as the country plodded along at a dismal 4 per cent rate of growth from the 1950s to the 1980s, called the ‘Hindu Rate of Growth’ by Indian economist Raj Krishna.

Despite the lack of economic power, India continued to dabble in regional and international affairs (Gaza, Congo, Korea, African colonies etc., to name a few), with critics questioning the logic of this high-brow diplomacy based on the Panchsheel Principles in the absence of comprehensive national power. Obviously, a post-colonial sense of inferiority contributed to this pessimism.

However, now all that seems to be changing, and in a big way. The question arises, is India on the right path or should it wait like China and bide time till its economic momentum becomes sustainable before venturing into the big bad world of international politics?

Background

On the face of it, the U.S. and India share attributes that would make them natural allies. The U.S. was the only major nation predominately inhibited by Caucasians that openly supported India’s freedom struggle. There are many features of the Indian constitution that resonate with the core values in the American Constitution- fundamental rights, impeachment of the President and apex court judiciary, the preamble etc. Evidently, Indian founding fathers were inspired by the American Declaration of Independence and took it as a template for their nation in its crucial formative years.

Yet, there were deep-seated differences due to the racial divide (for not being "free white people") prevailing in the 19th Century and early 20th Century. Only after World War II did the U.S. officially open the door to Indian immigration through the Luce–Celler Act of 1946 that permitted a quota of 100 Indians per year to immigrate to the U.S. It also allowed Indian immigrants to naturalise and become citizens of the U.S.

Yet the hope was never lost that the U.S. and India could come together someday. This hope manifested itself time and again. But in the end, they fell short in the face of hard political realities. Mutual suspicions remained high. The mutual cultural understanding was low. There was no incentive on either side to really engage with each other. Each party waited for the other one to make the first move. And so, nothing much happened.

Analysis

There were many reasons for this divergence between India and the United States. One was ideological. When India became independent, the main concern for the U.S. was international communism. This was the basis on which they made their foreign policy at the time. The emerging post-colonial world was a concern not only for the Americans but also for the Soviet Union. India was one of the first countries to gain its freedom from colonial powers. From the very beginning, it had a suspicion about Western powers. Many Indians saw the United States at the time as continuing the policy of the colonial powers through new means. This mindset has taken a long time to change. The U.S., too, has stopped seeing India through its own prism or from the angle of Pakistan.

Ideologically, America is no longer suspect in Indian eyes. Rather Indians now identify with the American model. India has become a serious partner of the United States and has yet to become an official ally. This is an achievement in itself.

The common thread of the English language was always there between India and the United States. But this only matters a little as long as interactions between the countries are low. Now English is bringing the two countries together. It is the lingua franca of India. The U.S. has recognised this fact. As a result, American businesses have come in droves to India to employ the English-educated Indian workforce.

It is said that one elephant is in the room, bringing India and the U.S. together. This is the continuing rise of the Chinese dragon and its implications. However, this is a simplistic reading of events. America cannot use India against China only to fulfil its agenda. India is more than just a tiny piece on the larger global chessboard.

It is a historical truth that India has never been coerced into following any foreign power or adhering to any economic model. And it is not going to start now. Indian interests will always come before that of the U.S. or any other country. This is non-negotiable.

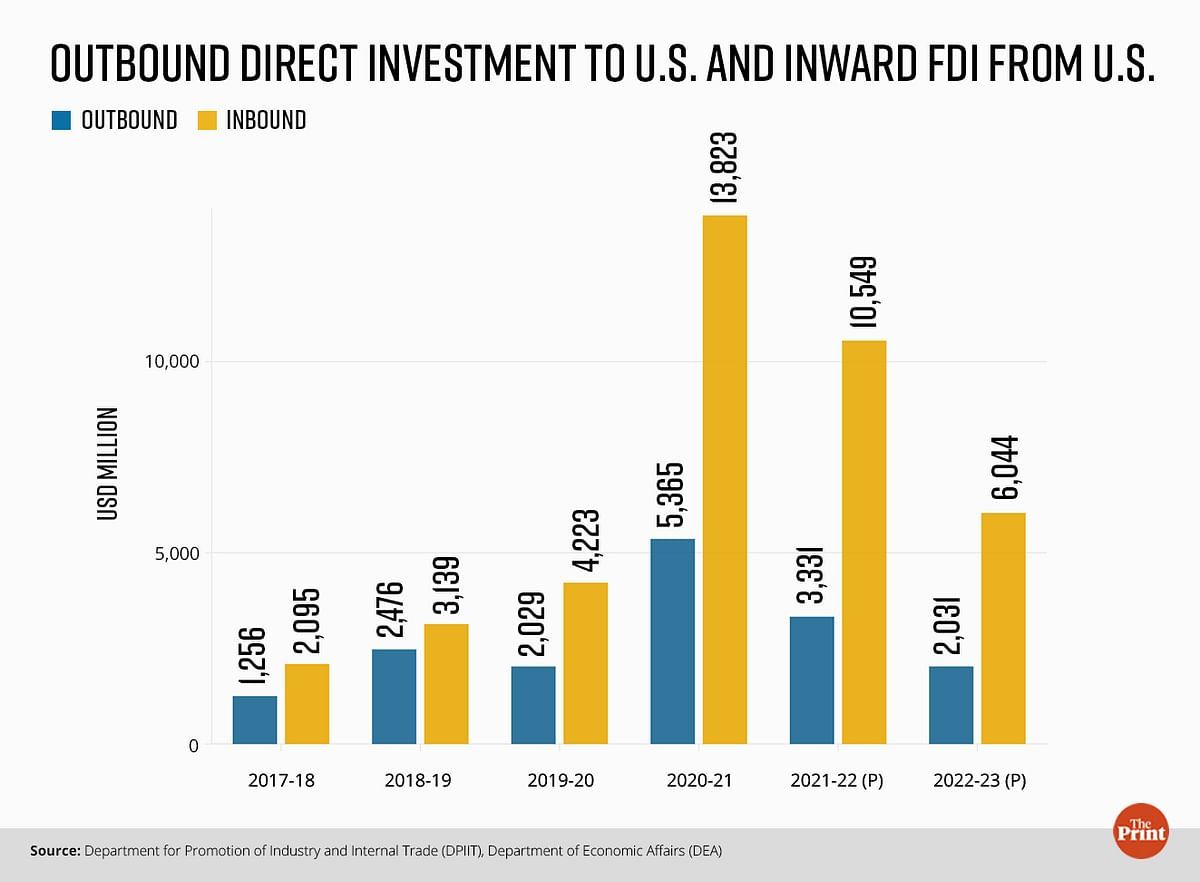

This is a relationship between equals that has multiple factors going for it at the moment. The booming Indian economy is obviously an attraction for Washington. The Indian market is huge. It is diverse. And it still needs to be completely exposed to the full extent of globalisation. So, the possibilities for American enterprises are endless.

Of course, the Chinese factor is essential. But it is necessary only in the broader context. The United States knows that it cannot always be present everywhere. Even a superpower has its limits which have been exposed time and again. The Indian Ocean region and the wider Indo-Pacific will be the next international strategic background. India is strategically located here. It has a long, contiguous coastline. Security in this region cannot be determined without India. It is the natural regional behemoth. New Delhi's significance will continue to rise as the new security architecture evolves in this critical maritime zone.

India had made a significant connection in America and other countries through the Indian diaspora. This group has emerged as a powerful entity in its own way.

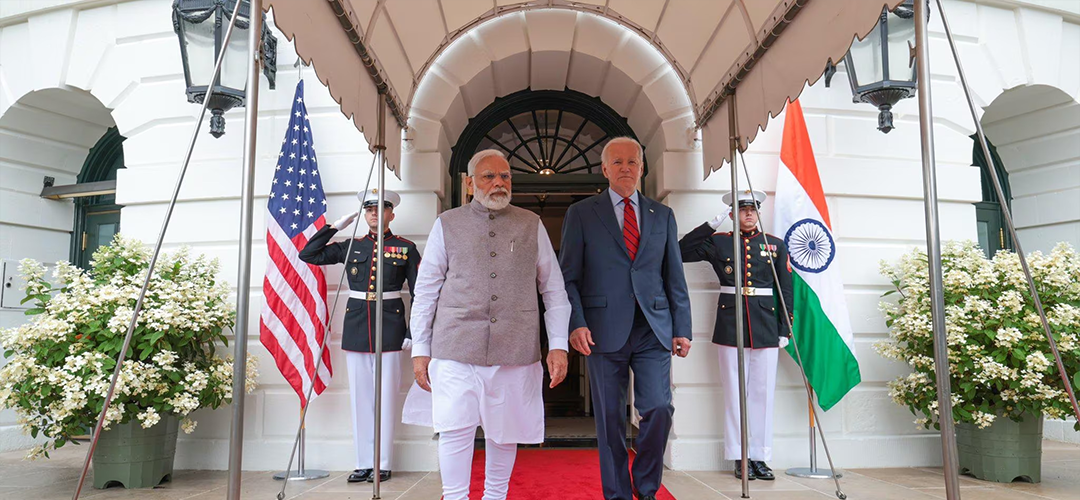

Taking the Prime Minister's latest visit to Washington, the major takeaway has been an agreement signed between the American company General Electric and the Indian Hindustan Aeronautical Limited to co-produce jet engines, an Achilles heel of the Indian aviation industry. Overall, defence industrial collaboration between the two countries will occur under the 'INDUS-X' platform. The presence of the American and Indian business sectors in this platform will add value to it.

Big private sector investments have been announced, especially in semiconductors which is a critical sector for the future. The ISRO will work closely with NASA to carry out joint missions in space. Again, the technical benefits to the Indian side will be worthwhile. As can be seen, the Indo-US relationship has taken on its own trajectory. This will continue irrespective of the change in government in either country.

Assessment

- The Indo-US relationship has evolved from official government-to-government to people-to-people, and now it has to transcend to a mutually beneficial private industry-to-industry collaboration and exchange. This is where the future lies; if we go by the current trends, the journey has just begun.

- There will never be a complete convergence of interests between India and the United States. New Delhi will continue to have its relationships with powers opposed to the U.S., like Russia and Iran. The Ukraine crisis is a clear example where the Indian viewpoint has been contrary but still accepted by Washington. If this level of maturity is displayed by both sides, accepting and respecting the core interests of each side, the prospects of the U.S.-India strategic partnership becoming a vital driver in international geopolitics will be high.

Comments