Chinks in Asia’s Armour

October 19, 2021 | Expert Insights

Mr. M K Narayanan was the National Security Adviser of India from 2005 to 2010. He also served as the Governor of West Bengal from 2010 to 2014. This article is based on his key talking points at the Plenary Sessions of the ‘World Policy Conference’ held in October 2021 in Abu Dhabi.

In today’s troubled world, Asia resembles 18th Century Europe, with its varied nations wracked by geopolitical rivalries and working at cross purposes with each other. Amidst all of them, China stands like a glowering giant, casting an ominous shadow over its neighbours. The series of alliances and pacts that have recently emerged in Asia and in the wider Indo-Pacific region, such as the QUAD and the AUKUS, reflect these widespread concerns.

Yet another country that symbolises the shambolic nature of Asian security is Afghanistan. Most countries in the region, especially democracies like India, have every reason to feel concerned over the recent developments in this country. With Pakistan and even China seizing to fill the vacuum left by the U.S. and NATO in the country, neighbouring countries India and the Central Asian Republics are deeply concerned.

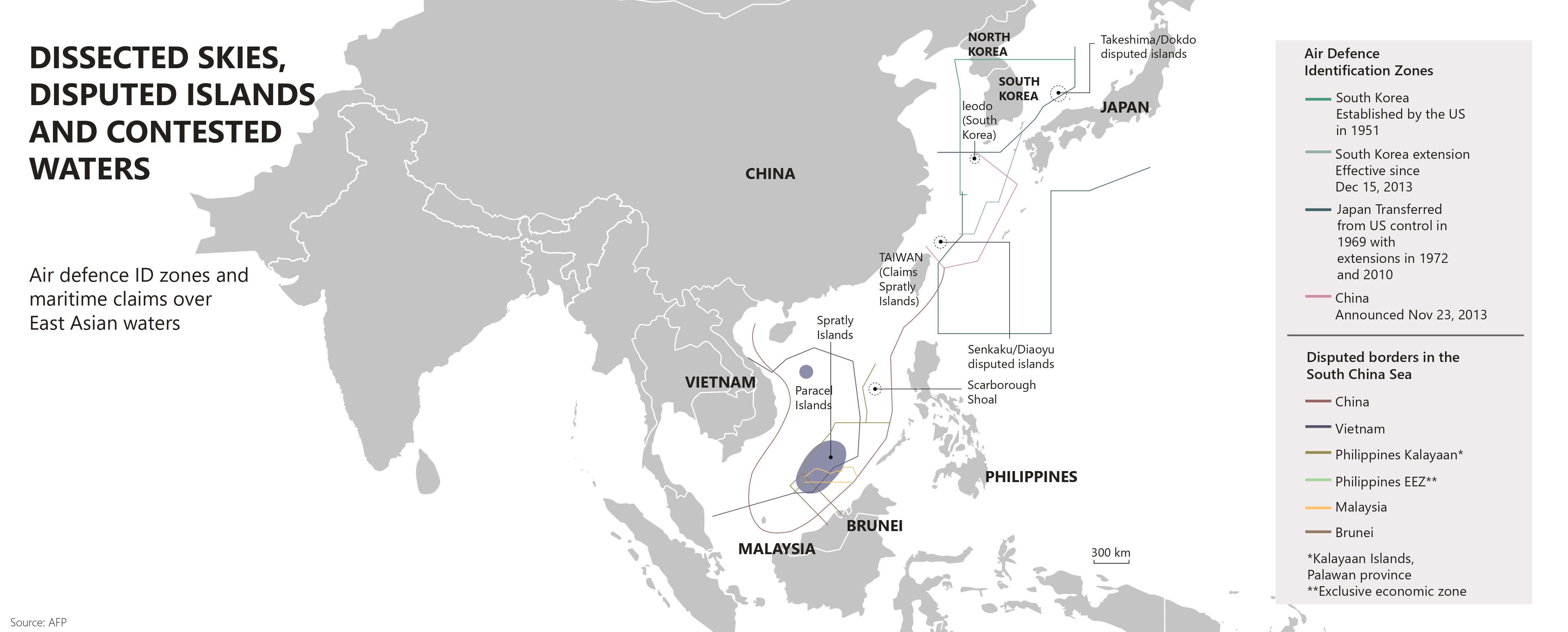

Though distant from Indian shores, there is hardly any need to underscore the serious nature of the China-Taiwan rivalry, which has intensified of late. This alone has the potential of becoming a major global conflagration that would embrace superpowers, such as the U.S. (and its close NATO allies) and China, apart from countries in the vicinity.

The fact that China is the common factor in most conflicts in Asia, will serve to remind people of Francis Fukoyama's warning that the new global strategic threat comes not from Islamic terror but from China. The world cannot set aside this innate wisdom, and any serious discussion on China-American rivalry cannot but factor this into their calculations.

THE INDIAN DILEMMA

From an Indian standpoint, the two most serious issues of concern are its immediate neighbours - Pakistan and China. One is the legacy of the erstwhile British Empire and its imperialist priorities, while the other is of relatively recent origin. While India has fought three-and-a-half wars with Pakistan (excluding the simmering proxy war waged through its proxies since the late 1980s), its tensions with China erupted in the late 1950s, following the backstabbing incursions of the PLA in 1962. These tensions continue to fester, leading to sporadic border skirmishes and frequent sabre-rattling. Since 2020, the Line of Actual Control (LAC) with China in Ladakh has become a 'hot' border.

Currently, the two largest nations of Asia, India and China, are in a state of (undeclared) confrontation. They share several thousand kilometres of an undefined, un-delineated (and contentious) border and have an uneasy relationship at best. This is now threatening to turn into an ugly conflict in the wake of China's unprovoked aggression in the Galwan Heights in Eastern Ladakh in the spring of 2020. Both sides have since substantially increased their military presence in this region, as also in many other sectors of the border.

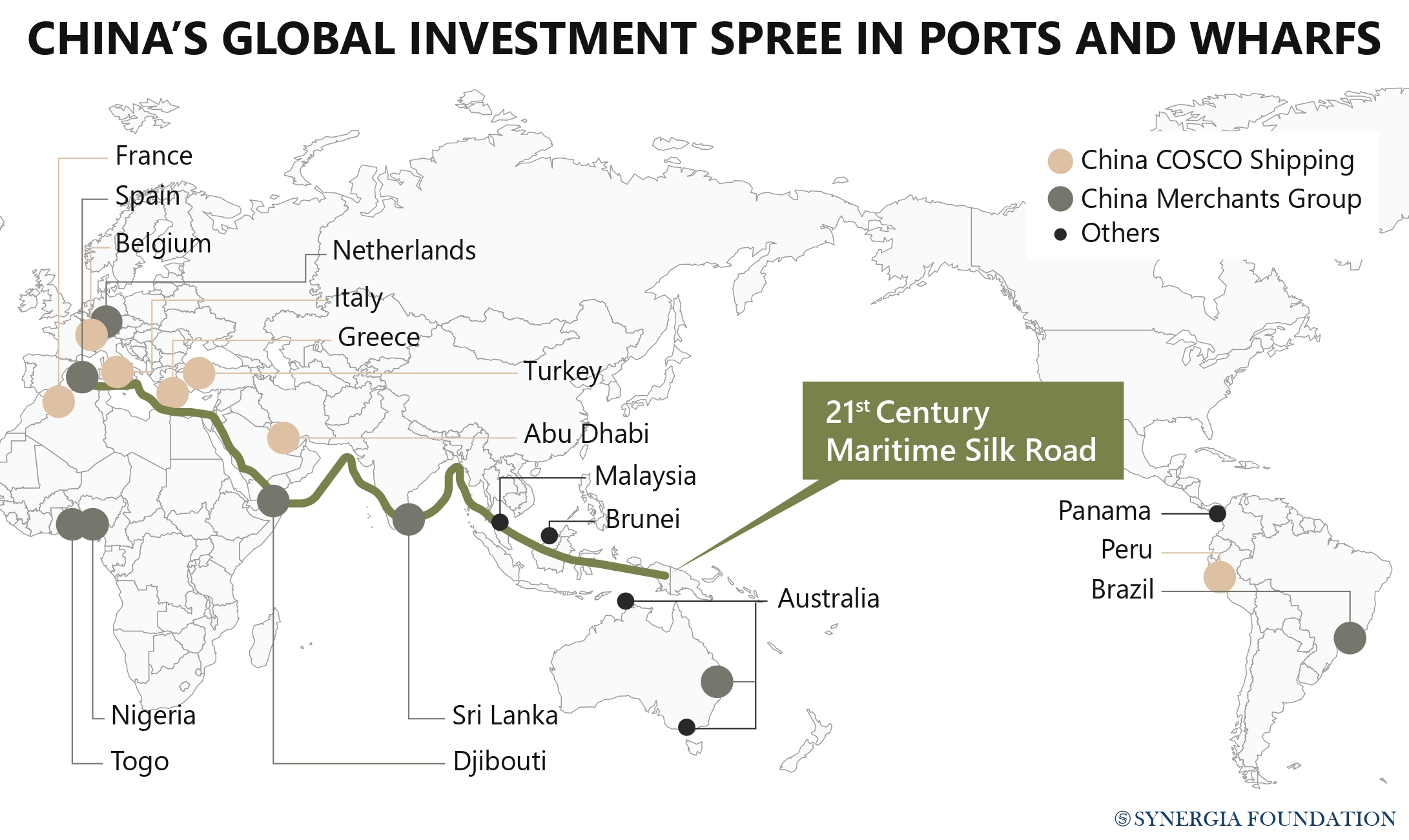

Among Asian nations, India is, perhaps, the only country that appears to have properly comprehended China's plans and the strategic imperatives behind China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), refusing to become a part of it. Today, many countries in Asia are not only willing to acquiesce in China's moves but have also ceded ground to China in return for economic and other favours.

India’s warm relationship with many of the countries in the region that are at the receiving end of China’s aggressive behaviour – and its own heightened tensions with China – means that it would be more than willing, and has the ability, to play a lead role in cementing an anti-China coalition of forces. India also has the moral authority to secure the backing of most Asian countries - with the sole exception of Pakistan - for any such endeavour.

THE INDO-PACIFIC PIVOT

Checkmating China's expansionist ambitions is crucial for the future of Asia, if not the world. There have been periods in the past when the U.S. has uttered brave words about the need to counter China whenever Sino-U.S. rivalries seemed to escalate– the ‘US pivot to Asia’ at the turn of the Century is one of them.

However, U.S. priorities appear to change with every new administration, in contrast to China which seems able to keep going ahead and ensure that most Asian nations remain in its thrall, apart from sending a warning to countries further afield. The question uppermost in Asian minds is whether the U.S. today is willing to ‘bite the bullet’ and ‘walk the talk’ when it comes to a confrontation with China. Their concerns are real, given the historical events of recent decades. Since Vietnam, the U.S. has seldom stood its ground when situations warranted it - Afghanistan being the latest example. It appears that other than India and possibly Vietnam, few Asian nations demonstrate a willingness to stand-up to China.

Another question that warrants an answer today is whether arrangements such as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) and the very recently established Australia-United Kingdom-the United States (AUKUS) partnership mark a new beginning and a determination on the part of the U.S. to counter China. If so, it would necessarily take U.S.-China rivalry to a new high, with major consequences for the future of the region.

A distinction has, however, to be made between QUAD and AUKUS. The former is essentially a plurilateral grouping that has many other facets, apart from security. The AUKUS, on the other hand, is essentially a security pact. Many countries in the region, India included, would welcome a display of determination and direction on the part of the U.S. The true success of these new groupings will, however, depend on the implementation of their plans. Given the recent brouhaha between France, and the U.S., UK and Australia, there is a real concern in Asia whether the new arrangements will indeed achieve the signal purpose of restricting and containing China.

PERPETUALLY ON THE BOIL

As far as Afghanistan is concerned, Taliban’s ability to govern its disparate sections, even though it has achieved control as of now, is a question that begs an answer. After weeks of dilly-dallying, it has announced a government consisting solely of Pashtuns but have since expanded it to include certain other tribes like Tajiks, Hazaras and Uzbeks.

The result sheet of two decades of foreign intervention in Afghanistan has essentially been negative. None of the objectives sought to be achieved by the U.S. and NATO-led intervention have been achieved. The primary objective of U.S. intervention in Afghanistan, viz., to destroy terror networks such as Al Qaeda, for instance, has not happened. The Al Qaeda network, far from being destroyed, has returned in force. It is, perhaps, stronger today. Newer outfits such as Daesh, the Islamic State as well as ISIS-K, have lately made their presence felt across the region.

Can the Taliban ensure stability in Afghanistan? This remains highly doubtful. There are too many contrary influences at work. Apart from the fact that Afghanistan is hardly a country understood in modern times, it has never been in the nation’s DNA to accept centralised authority. What is, perhaps, of even greater concern for countries in its neighbourhood is that the newly constituted Afghan Government comprises several individuals who figure in terror lists worldwide, including that of the United Nations and countries like the U.S.

Also, not to be underestimated is the strong possibility of an internal power struggle between its two main strands, viz., The Quetta Shura and the Miran Shah Shura controlled by the Haqqani network, which is linked to Pakistan. It could result in endemic violence along tribal fault lines leading to disastrous consequences, not only for Afghanistan but for the Asian region, and in particular, South Asia.

THE GREAT GAME ONCE AGAIN

The geopolitical impact of the Taliban takeover in Afghanistan is only beginning to unfold. It is, however, unlikely to enhance peace in the Asian region or even beyond. As of now, what is apparent is that different countries are responding to the Taliban in different and diverse ways, based on their individual calculations.

This is very different from the situation that prevailed in the 1980s and the 1990s when the Taliban were completely isolated, and Pakistan was its sole benefactor. Today, China is apparently willing to risk dealing with a Talibanised Afghanistan, given its mineral wealth and strategic location. This, notwithstanding the fact that China is deeply concerned about the possible links between the Taliban and its Uighur minority.

Russia, for its part, has not shunned a Taliban Afghanistan, partly because it has been in touch with the Taliban in recent years and in the backdrop of its Eurasian ambitions.

This newfound affinity for the Taliban is not confined to the major powers only. Quite a few nations of West Asia – including it would seem Iran – also seem to display a willingness to have dealings with a Taliban-led Afghanistan and are finding ways and excuses to do so. Pakistan is the one nation, though, that has openly welcomed the Taliban takeover.

FRESH ROUND OF TERROR?

This time around, with Jihadists worldwide feeling electrified by the Taliban’s latest success, the concerns of regional countries are even deeper than in the 1980s and 1990s. India, for instance, is worried that it may well have to deal with not only the Lashkar-e-Taiba and the Jaish-e-Mohammed, but many newer terror variants such as the Islamic State, especially the ISIS-K.

Adding to the terror threat is the danger posed by drugs, especially Opium. The drug route from Afghanistan via other Asian nations has been revived. For the cash-strapped Taliban, the opium trade could prove an easy means to raise funds. This would pose a global threat of no mean magnitude.

The world should, therefore, take note of the gravity of the situation posed by the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan. Afghanistan is, in every sense, a South Asian tragedy. Even as the U.S. retreats from Afghanistan, there is a growing body of nations in the West that is, however, seeking to impose a Western solution to what is primarily an Asian problem, or more precisely, a South Asian problem. This would be extremely short-sighted.

However, it is a fact that the impact of the latest developments in Afghanistan, and more precisely the presence of Talibanised Afghanistan, will be felt across the globe. For this reason alone, the matter is serious enough for all concerned nations to try and attempt at establishing a Global Concert, like the Concert of Europe in an earlier Century. This alone can provide a degree of stability to the region.

Current rivalries like that between the U.S. and China, the U.S., and the Soviet Union, and among certain other countries of the region and beyond, must not be allowed to stand in the way of creating such a Global Concert. Nations in Afghanistan's neighbourhood, such as India, which have long-standing links with Afghanistan, must be involved in this effort. Setting up a new concert of nations of this kind would, however, demand both ideological diversity as well as strategic accommodation. Overcoming the odds is not going to be easy, but every effort must be made to achieve this objective.

Comments