Chequer-Mating Theresa May

November 15, 2018 | Expert Insights

Negotiators for the EU and the UK have finally struck a draft deal on the conditions of the British divorce from the bloc. But now Theresa May has to convince her Cabinet and Parliament to back the deal.

Background

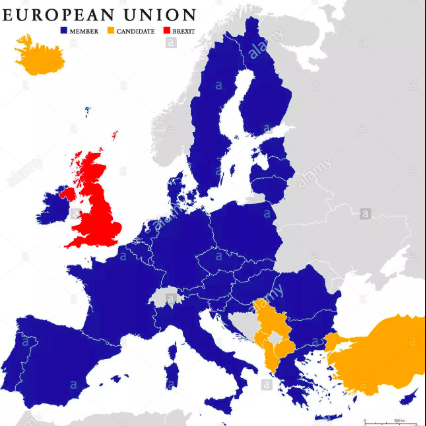

Brexit, or the "British exit from the European Union", is the proposed withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the EU. It follows from the referendum of 23 June 2016 when 52 per cent of those who voted in the referendum supported withdrawal. On 29 March 2017, the UK government invoked Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union. The United Kingdom is due to leave the EU on 29 March 2019 at 11 p.m. UK time, when the period for negotiating a withdrawal agreement will end unless an extension is agreed. The UK had joined the European Communities (EC) in 1973, with membership confirmed by a referendum in 1975. Prime Minister David Cameron held the referendum to leave the EU in fulfilment of a 2015 manifesto pledge. Cameron, who had campaigned for "Remain", resigned after the referendum result and was succeeded by Theresa May, who called a snap general election less than a year later, in which she lost her overall majority. Her minority government is supported in key votes by the Democratic Unionist Party.

The UK and EU have provisionally agreed on the three "divorce" issues of how much money the UK owes the EU, what happens to the Northern Ireland border and what happens to UK citizens living elsewhere in the EU and EU citizens living in the UK. Talks are now focusing on the detail of how to avoid having a physical Northern Ireland border, and on future relations. To buy more time, the two sides have agreed on a 21-month "transition" period from March 2019 to December 2020 to smooth the way to post-Brexit relations. The UK cabinet has agreed on how it sees those future relations working, but this plan, often called the Chequers Plan because it was agreed at the PM's country residence, has faced criticism from anti-Brexit campaigners, some leading pro-Brexit Conservatives, and also from the EU, which has said key parts won't work.

Analysis

The UK and EU officials are said to have reached agreement on the withdrawal agreement and a declaration of how the UK-EU relationship will work after Brexit. The UK cabinet will discuss the text on 14 November. If they give the go-ahead there should be an EU summit at the end of November to agree to it. It would then be up to the UK parliament and EU member states to each ratify the agreement, before Brexit day next March.

According to Ireland's public broadcaster RTE, the text resolves the Irish border issue, a fundamental sticking point in negotiations.

May faces an uphill battle getting politicians to agree to the deal, with several warning they would vote against it if it was not to their liking.

Brexit zealot Boris Johnson, who resigned as foreign secretary in July, said he would not support the deal.

The conservative Northern Irish DUP party, which props up May's minority government, said it would wait and see the actual text of the deal, which is reportedly hundreds of pages long, before deciding how it would vote.

Jeremy Corbyn, leader of the opposition Labour Party, said: "We will look at the details of what has been agreed when they are available. But from what we know of the shambolic handling of these negotiations, this is unlikely to be a good deal for the country."

Hard-line Brexit supporter Jacob Rees-Mogg said: "I hope the Cabinet will block it and if not, I hope Parliament will block it. I think what we know of this deal is deeply unsatisfactory.”

Senior cabinet ministers led by Brexit secretary Dominic Raab are planning to tell Theresa May that the current deal on offer from the EU is unacceptable and she should prepare for the UK to leave with no deal if she cannot secure further concessions.

Assessment

Our assessment is that the EU is unlikely to yield in this negotiation, as they will hope to make an example of the UK to deter any other nation from leaving the union. We believe a more likely outcome is an extension, which would be beneficial to the UK as two years is too short a time to make all the legislative and policy changes to ensure stability in the post-Brexit UK. We also feel that however it is negotiated, Brexit is likely to reduce the UK's real per capita income in the medium term and long term.

Comments