Banishing Tobacco for Good?

December 16, 2023 | Expert Insights

Civil society around the world, including India, has taken up the cudgels against smoking in public places. However, the consumption of tobacco products, highly profitable for both manufacturers and a tax-hungry state, remains high. That this addictive substance has well-proven health hazards is no less relevant and a matter of grave concern.

It may be recollected that a famous 1991 landmark lawsuit filed against the tobacco industry in the U.S. for $5 billion (on behalf of 60,000 serving and retired flight attendants for alleged harm suffered by their bodies from second-hand smoke) brought even greater attention to the harmful effects of tobacco. Of course, the 1997 verdict on the suit let the powerful tobacco industry slip away with just a rap on the knuckles- a miserly $300 million donation to establish a medical foundation to study illnesses linked to tobacco smoke!

In India, while regulations try to curb its usage through restrictions on indoor smoking and advertising of tobacco products, this does not adequately address the problem. Even of greater concern is that other, even more dangerous forms of tobacco consumption, like chewing tobacco (gutka) and beedis, are consumed in much higher proportions by the masses than cigarettes. These products are harder to regulate since they are sold at street shops and kiosks, and medical research has proven that their health dangers are even more serious.

Of course, everything boils down to economics! In the case of tobacco consumption, there are socio-economic considerations - products like beedis provide livelihoods to millions, largely female workers from the marginalised classes. Further, the tobacco industry provides two-fold revenue to the government through sales (the government has a significant stake in tobacco production) and taxes.

Background

India has the second-largest number of tobacco users in the world (after China). Tobacco use contributes to diseases like cancer and chronic lung disease; it accounts for almost 27 per cent of all cancers in the country; India has the highest number of cases of oral cancers in the world; and around 27 crore people above age 15, and 8.5 per cent of teenage children between ages 13 and 15 smoke. Tobacco's healthcare implications cause an annual economic burden (of more than Rs. 1,77,340 crore) arising from the cost of treatment and work hours lost.

Exposure to second-hand smoke is still widespread and can substantially affect health. It is linked with cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory issues, and a higher risk of lung cancer. In children, it is a major cause of asthma, pneumonia, and bronchitis.

Several countries have passed laws and regulations to protect clean indoor air, such as laws for smoke-free restaurants, bars, workplaces, public transport, and other public places. Some countries leading the way in substantial laws for clean indoor air include New Zealand, Norway, and Ireland.

While these policies reduce the prevalence of smoking, they also play a role in denormalising smoking. In other words, they contribute to changing social norms and attitudes towards smoking. This is particularly the case for smoking in public spaces, such as having 100 per cent smoke-free workplaces and no smoking in restaurants, bars, airports, and even pubs and casinos. In India, it is an offence to smoke in public places that, include streets, markets, railway stations, government offices etc.

However, several Indian restaurants, bars, airports, and hotels are not subject to clean indoor air laws. Many have smoking rooms or separate smoking and no-smoking zones.

The tobacco industry wields considerable power when it comes to passing regulations in the parliament against the consumption of tobacco. In 2021, the Indian tobacco industry objected to a proposal to ban smoking zones in hotels, restaurants, and airports, as well as advertising at cigarette kiosks, and increase the minimum legal age for smoking to 21 from 18. Opposition to the proposal argued that it would hit sales of companies like ITC, Godfrey Phillips India, and a unit of Philip Morris International, players in the country's $12 billion cigarette market. Earlier, major changes to tobacco control laws proposed in 2015 were abandoned due to tobacco industry protests.

There has also been an ongoing debate about banning the sale of loose cigarettes, a popular habit in India where many consumers buy a few cigarettes from the street vendor and not a complete pack of 10s or 20s. A Parliamentary Standing Committee recently recommended banning the sale of single cigarettes since they affect government efforts to control tobacco use. Given the recommendation, there has been speculation that the sale of loose cigarettes will be banned across the country, with cigarettes only being sold in boxes. This will again impact the street-level vendors who make a little extra profit from the sale of these loose cigarettes since their low-income customers cannot afford to purchase a full pack at a time. Himachal Pradesh has already passed a law banning the sale of loose cigarettes and beedis.

Analysis

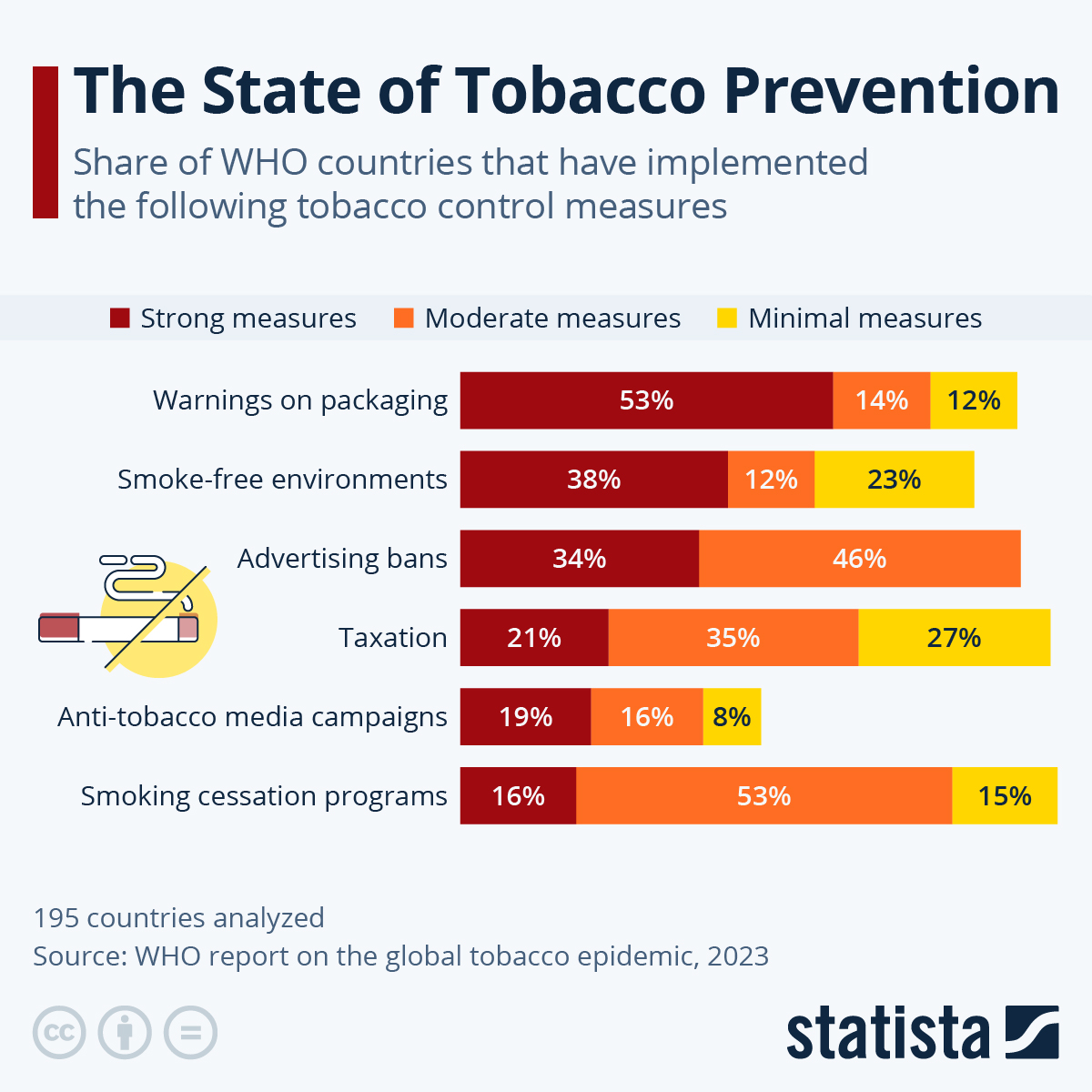

Many argue that indoor smoking bans and designated smoking zones are inadequate to curb widespread tobacco use and smoking by Indians. The issue of second-hand exposure persists. Smoking rooms do not effectively control it. Further, graphic warnings on packages, advertising bans, and punitive taxation are not likely to effectively deter tobacco dependents.

Critics argue that the government is reluctant to eliminate tobacco use because of its significant stake in the tobacco industry and the substantial taxation revenue it generates. However, other factors complicate the feasibility of a ban on tobacco. These include the large number of workers and farmers who contribute to the tobacco industry that stand to lose their livelihoods. Provision would have to be made to train and re-skill such workers for alternative employment. Another issue is that banning tobacco products will risk handing them over to the black market, out of the purview of regulations. This has been graphically shown in states that ban alcohol and thus encourage a flourishing underground liquor mafia to proliferate.

While taxes on tobacco products in India are high, they fall far short of the WHO standard of 75 per cent of the retail price recommended to discourage tobacco use. Yet, higher taxes on products like beedis could substantially impact beedi workers’ incomes.

However, despite these socio-economic repercussions, the ICMR (Indian Council of Medical Research) has argued that the health costs of tobacco outweigh its economic gains: it has estimated that tobacco income falls far short of the health expenditure arising from tobacco-associated diseases. It also projected that the health cost would rise unless further tobacco consumption is halted.

The government banned electronic cigarettes or e-cigarettes in the interest of public health in 2019. Many questioned this move on the basis that e-cigarettes are a lesser evil and present a less hazardous option to smokers. Yet, it cannot be denied that e-cigarettes present health risks - in addition to nicotine (which they contain), the flavouring and additive agents produce carcinogenic compounds when heated. Based on the precautionary principle, the move was justified as a preventive one to halt the rise of e-cigarettes. However, regulating vaping is still an issue due to the black market.

This illustrates the possible aftermath of banning tobacco products - the difficulty in enforcing it and encouraging a transition to a vast black market. After all, marijuana and hard drugs like cocaine are also strictly banned globally, but has their consumption stopped or declined?

Assessment

- The issue of widespread tobacco use and smoking in India cannot be tackled only by restricting ancillary activities such as smoking in restaurants and offices. While such restrictions are important in protecting indoor air, they do not prevent second-hand exposure.

- Potential bans on tobacco products will likely have to be accompanied by measures to support the workers affected in finding alternative livelihoods. While the black market remains a problem to reckon with for such bans, it cannot be denied that nothing short of a total ban would discourage tobacco use.

- State government measures can play an important role in combatting products like chewable tobacco, single cigarettes, and beedis. However, products like packaged cigarettes are unlikely to be banned, given the substantial public revenue they generate.

Comments