Amul Vs Nandini: Crying Over Split Milk?

April 29, 2023 | Expert Insights

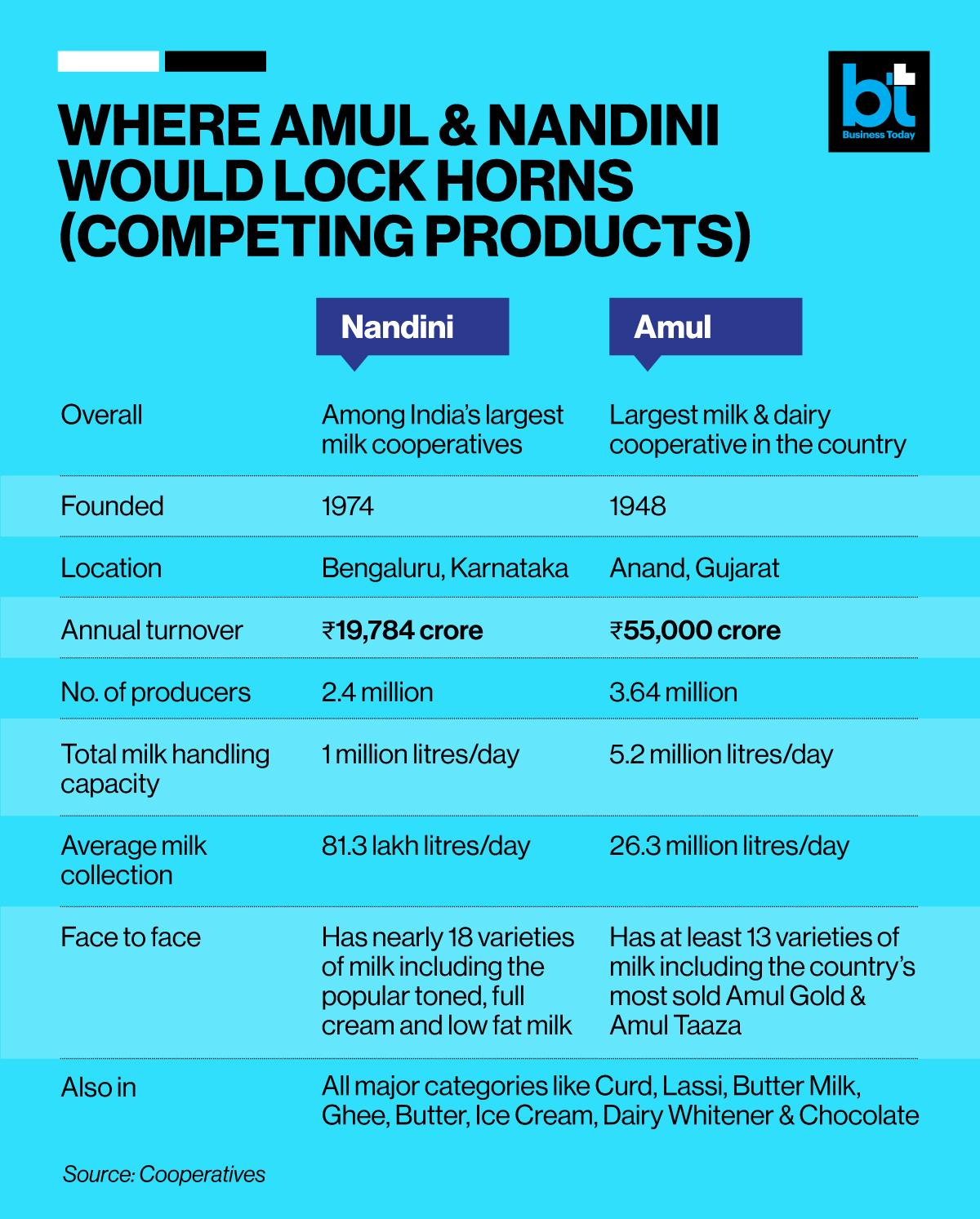

Amul’s, an internationally recognised brand, recently announced that it would enter Karnataka's highly lucrative daily supply of milk market. While the Gujarat government-owned cooperative society may have expected stiff competition with similar government-owned cooperative suppliers of Karnataka, it failed to anticipate the political storm it would trigger. As for the political parties jockeying for positions in an election whose outcome is still unclear, it was an opportunity to embarrass the ruling BJP.

The opposition, Congress and Janta Dal (Secular), claimed it would destroy the livelihood of 2.5 million milk farmers who depend upon their cooperative, the Karnataka Milk Federation, whose brand name Nandini dominates the milk, curd and dairy products market in the state. The battle quickly escalated to social media, with hashtags #Save Nandini and # Goback Amul trending.

Incidentally, the Nandini brand is the second largest in the country after Amul, and its foray into neighbouring Kerala has met with identical resistance from Kerala's milk cooperative Milma.

Background

The cooperative dairy movement in India began in 1946 when the first farmers' dairy cooperative was set up in Gujarat. This cooperative is commonly known as Amul (Anand Milk Union Limited). Its model became globally famous as the Anand model, which was subsequently replicated in dairy cooperatives across the country. In fact, it inspired a famous 1976 film, “Manthan” (The Churning), directed by well-known director Shyam Benegal.

At the outset of the cooperative dairy movement, the principle of cooperation was promoted to prevent conflict of interests. The concept of a milk shed delineated different market areas, and the responsibility for milk marketing was with the state-level federation. However, competition grew as the domestic market opened up with liberalisation and globalisation. The dairy cooperatives began to expand their network and look for areas outside their operational areas to market their milk.

As they entered new cities, there were conflicting interests between the existing cooperatives marketing their milk in the cities. Competition increasingly outweighed the principle of cooperation. However, in certain cases, expansion was not a competing move but took place to fill the market gaps where the existing supply did not meet the demand. Moreover, while the brands competed for long shelf-life products, the market for liquid milk usually belonged to the local cooperative, honouring the principle of cooperation.

As Amul grew as a brand, it expanded its market beyond Gujarat. It usually started with selling liquid milk and establishing its brand as a supplier. It would then establish a procurement network and processing facilities, and its establishment was often to the detriment of the local brand.

While Amul products are available in Karnataka, it currently does not offer fresh milk products, such as liquid milk and fresh curd.

Analysis

However, cross-border marketing by milk cooperatives is not new. Milk cooperatives have marketed and sold their products in other states and widened their market across state borders. For example, Amul entered the Delhi, Mumbai, and Kolkata markets as well as the cities of Kanpur, Lucknow, Allahabad, and Jaipur. Similarly, Bihar’s milk brand Sudha entered the markets of Varanasi, Kolkata, and Delhi. Yet, this particular instance involving the country's two largest milk cooperatives has led to heated controversy for several reasons.

Amul’s entry into the Karnataka market may not be a cause for concern for Nandini, given that Nandini has an extensive network, a strong union, and offers competitive prices. On the other hand, the apprehensions expressed by Nandini are echoed by Kerala’s Milma brand. According to the chairman of Milma, entering the market of another state goes against practices of courteous business relations amongst milk cooperatives. The chairman pointed out that cross-border marketing of liquid milk should be avoided since it encroaches on the sale area of the concerned state and leads to unhealthy competition.

Many experts, however, point to the surcharged political climate of Karnataka, poised for elections in the next two weeks, for the controversy.

Firstly, milk cooperatives in Karnataka hold substantial political influence. The KMF's network includes 22,000 villages and 24 lakh milk producers and is organised over 14,000 cooperative societies. Many milk producers are from key electoral constituencies since they cover around 120-130 assembly seats (Indian Express, April 10, 2022). The KMF milk cooperative covers not just Congress and JD strongholds but also Central Karnataka, where Lingayats are politically influential. The Lingayats have emerged as BJP’s support base in the state.

The Centre-state dynamic has added an additional political element to the public row. Ardent federalists are viewing Amul's entry into the Karnataka market as further watering down of state powers by the Centre.

Since Gujarat is the Prime Minister's home state, a shot fired against Amul is a direct accusation against the BJP-controlled Centre for influencing Karnataka's lucrative daily milk supply market in favour of the Gujarat-based Amul. Additionally, while cooperatives are a state subject, the Centre set up a new Ministry for Cooperation, which was viewed as a move by the Centre to gain more authority over state cooperatives. Further, the Centre's recent proposal that all curd packets be labelled "dahi" met with strong opposition in Karnataka as it was viewed as another move by the Centre to impose Hindi on the states.

Assessment

- Amul has a history of expanding into other state and city markets and establishing its brand. However, in this case, the KMF is a substantial milk cooperative to reckon with. Irrespective of whether Amul’s entry is a cause for concern or not, the Amul vs. Nandini issue has been politicised into a state-wide controversy. The political influence of the milk cooperatives in Karnataka, the upcoming state assembly elections, and the Centre-State aspect of the issue have all combined to make it a significant political row.

- Logically, in a free market environment, giving greater choices to the customer should be the way ahead, and the customer should be the final arbitrator on the merits of the two brands. However, daily production is intrinsically linked to the falling incomes of the rural communities in India, already struggling to survive, and this aspect cannot be ignored.

- After all, India has a very restrictive policy in permitting foreign dairy and farm products from developed countries like the U.S., EU and Australia from entering the Indian market, even if they would be less costly and provide greater variety for the sole purpose of safeguarding the interests of the Indian farmers. The same logic could be carried forward to the ongoing protests in Karnataka.

Comments