Estonian Perspective of Cyber Security

May 18, 2020 | Expert Insights

Lauri Aasmann:

Mr Lauri Aasmann is the Director of Cyber Security, Information System Authority of Estonia (exercising as NCSC, including CIIP and CERT-EE). Previously, he served as the Head of Law Branch at NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence which he joined in 2011 to work on legal issues related to cyberspace as a threat vector. Since 2019, Mr Aasmann is an Ambassador of the NATO CCDCOE, an honorary title awarded to a former staff member who continues an affiliation with the CCDCOE and contributes to building new partnerships.

Labelled as the "Digital Republic" by the New Yorker magazine in a 2017 article for creating a system of governance that is virtual, borderless, block-chained and secure, Estonia enjoys a unique reputation amongst cyber warriors. This tiny ex-Soviet country with a population of 1.3 million faced a barrage of cyber-attacks in 2007, which have often been referred to in informed circles as the "world's first cyber war." Estonia faced what was akin to a digital shutdown in 2007 when Russia allegedly attacked its servers over the relocation of a Soviet-era Bronze Soldier monument.

Taking a cue from this, Estonians are pathfinders who have built an efficient, secure and transparent ecosystem which proved its value during the ongoing pandemic. Not surprisingly, the prestigious Wired magazine named it the "most advanced digital society in the world!"

Drawing on the experiences of his country, Mr Lauri Aasmann explains, "The investments in the systems need to be made according to the sketches of the experts so that they don't collapse in their final hours, but rather we would be able to keep them up and running safely in emergency situations."

Learning from the experience, Estonia went on to become a global heavyweight in cybersecurity-related knowledge and now advises and trains many others – including NATO. In Estonia, NATO organised its largest cyber defence exercise in December 2016. The Tallinn-based NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence (CCD COE) – an independent military organisation set up in 2008 and was directed and funded by voluntarily participating states – focusing on training and education in both technical and non technical aspects of cyber defence, research and development.

Estonia's cybersecurity rests on a high-functioning e-government infrastructure, reliable digital identity, mandatory security for government authorities, and a central system for reporting, monitoring and resolving incidents. There is also a common understanding between the government and its citizens that cybersecurity can only be ensured through cooperation, and a joint contribution at all levels – state, private, and individual.

"COVID which required physical distancing proved that Estonia had made a wise choice in investing in digital services," said Mr Aasmann. "Even today, to the extent all the public sector is working successfully from their home offices, and all the public services are up and running." Estonia also managed to pick up on the 50% increase in the incidents that the CERT picked up, which was then understood to be scams and hacks under the guise of COVID-related themes, for which they took the appropriate responses, ensuring important sectors like the medical sector were not impacted.

Widespread use of digital technology on a routine basis also invariably helped during COVID, allowing for important government sectors to function and people to work from home. To cite one instance, the health care sector resorted to an online prescription system, which would allow for people to get their prescriptions online.

Not all things were cheery though. Estonia also struggled with the security of remote office tools. Mr Aasmann said, "there are hundreds of web conference tools which promise secured and end to end encryption connection, but they don't always deliver what they promise, and because the remote office grew to that massive a scale which we have never practised before, it was a complete mess in the beginning we have developed a backup system very quickly and efficiently, so there are now solutions for that." There was also the issue of having "old legacy IT systems," based upon old cabling which was error-prone and had to be replaced.

As for the way the world would respond to threats to critical infrastructure post-COVID, Mr Aasmann opined that the duration of the pandemic was too short to change the nature of cyber threats radically. Cybersecurity challenges are unlikely to change dramatically, although some aspects of the country's defence would need re-calibration.

There would be a change in the vulnerability of those who surf the internet vis-a-vis working from home, as this would continue in some significant capacity after the crisis is dealt with. To the layers of physical and cybersecurity the critical infrastructure, there would be a need to look at a third layer - the remote work environment. This particular environment will grow in size and significance as corporates realise its efficacy and value, provide it is made secure at a larger scale so that all users, as also the official networks are kept safe.

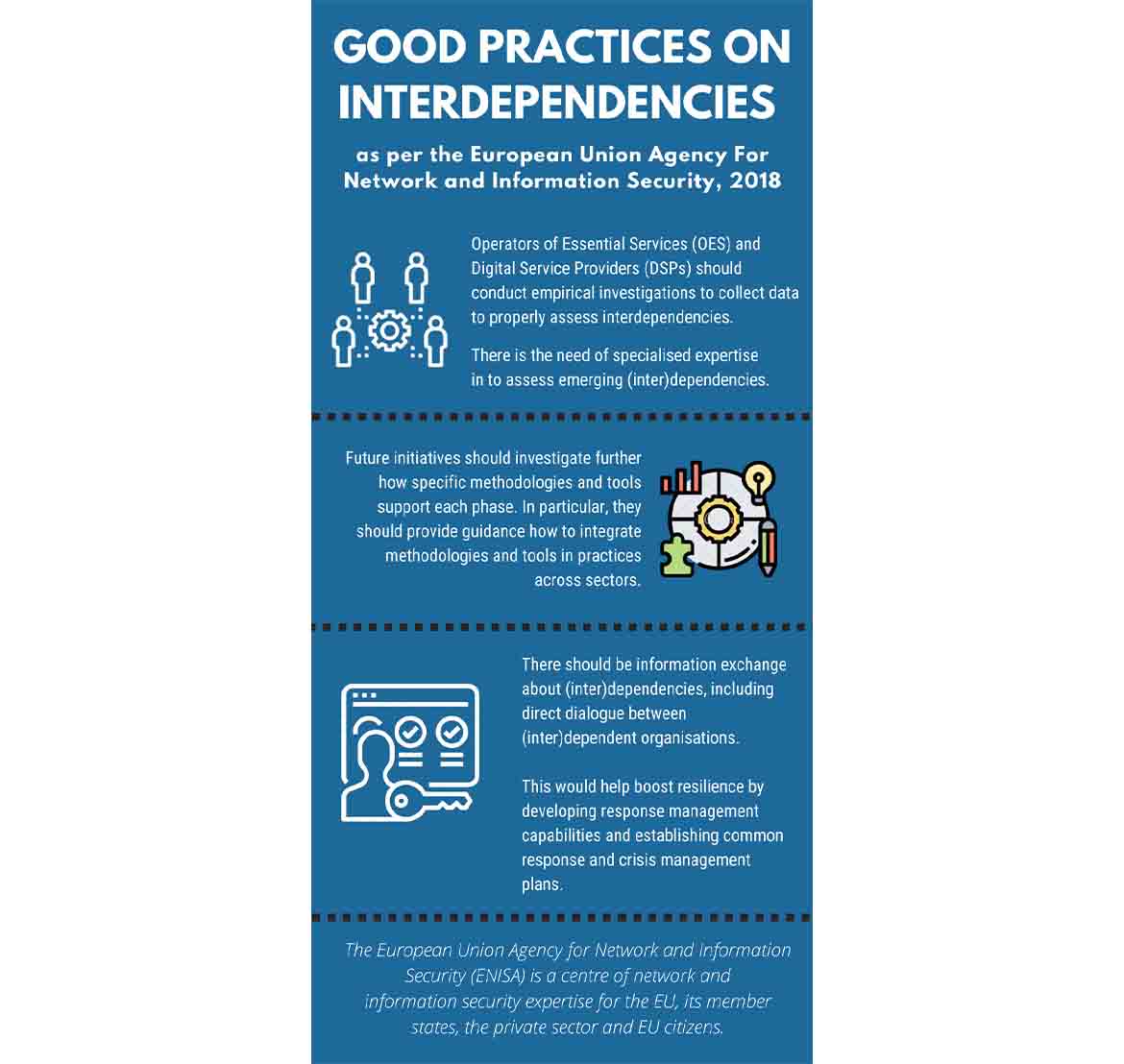

Inter sectorial dependency

While the internet has made critical infrastructure more complex, it has also increased its independency and fragility. Due to this interdependency, the impact of a single point cyber attack would be spread over various interdependent sectors of the economy/ business/ government, leading to a catastrophic collapse of multiple systems. The 2017 WannaCry ransomware attack on UK's National Health Service is a prime example. Lasting over several days, it disrupted the entire NHS functioning with over 19,000 appointments getting cancelled. Similarly, in Denmark, the headquarters of Maersk (incumbent for around one-fifth of the world's shipping) was brought to a standstill by NotPetya malware, causing disruptions at port facilities worldwide.

While highlighting such vulnerabilities, Mr Aasmann defined the ideal solution. In case cyberattacks disrupt supply chains, then it would be best to take a fresh look at all our supply chains to identify vulnerabilities and fix them now when we have the time "As a pragmatic person I would suggest taking those supply chains into very small pieces, and then we have to see which actors are involved in each step of the way. So, yeah, we need to pick things apart and then fix them together to see what is the glue that binds them."

Trust-building in cybersecurity

The World Economic Forum's Global Risks Report of 2019 ranked cyberattacks among the top-five risks. It is not surprising then that the value of the cybersecurity market is estimated to grow from $112 billion in 2018 to $281 billion by 2027.

Two aspects are relevant when it comes to handling cybersecurity at the most basic and individual level: stability and trust. Without effective security measures in place and the cooperation of the public to use them, cyber threats would undermine the stability of modern-day societies, making digital technologies a source of risk rather than development. Security in this form, for users, should be free but not at the cost of their lives or wallets, along with being transparent in its approach. The private sector bears significant responsibility for developing and improving new cybersecurity methods for the services and products they offer along with collaborating with the public sector.

When it comes to building a functioning digital society, Mr Aasmann draws on the Estonian experience. "Trust will be the cornerstone, and unfortunately, it is very fragile. You can easily lose it, and as soon as you start implementing things that are not transparent. So, with that, I want to say that security is important, but security cannot be achieved at the cost of the liberties. I personally feel, and my office is a strong believer in keeping encrypted systems encrypted."

Assessment

- The world can learn from the experiences of Estonia in cybersecurity and adopt some of its best practices. The size of the target population is insignificant as the model can be adapted for a larger population base like that of India.

- However, a word of caution may be necessary as total dependency upon digital-based systems to run critical networks/ systems may prove disastrous, more so when such systems are interconnected and power run. Redundancy, including some based upon old legacy systems, would be prudent. Wired/ OFC based communication systems are good examples of such redundancies to the more popular 4G/ 5G systems.

Comments