Disruption in South Asian Geopolitics

May 30, 2019 | Expert Insights

We live in times of transformational change and the pace of that change is increasing. Over centuries, professional armed forces across nations have been at the forefront of these changes.

What can corporates learn from military history so that they can benefit from the concept, ‘dare to disrupt’ as a strategy?

Our series, ‘Dare to Disrupt’, draws lessons for businesses using illustrations from military and counter-terrorism history.

This second article in the series, authored by Maj. Gen. Moni Chandi (Retd.), shows that not just anyone can dare to disrupt; those who do must be willing to take risks.

The Unwanted Electoral Verdict

In August 1947, when India got Independence, Pakistan comprised East Pakistan (present Bangladesh) and West Pakistan (present Pakistan). Though, East Pakistan was more populous than West Pakistan, political, economic and military power was concentrated in West Pakistan. In 1970, Pakistan held General Elections and an East Pakistani political party called Awami League won an astonishing 290 of 310 seats in the Provincial Assembly of East Pakistan. The landslide victory assured the Awami League of an absolute majority in Pakistan’s National Assembly and the President of the Awami League, Sheikh Mujibur Rehman (popularly called Bangabandu) was assured of becoming PM of Pakistan. However, many in West Pakistan were not happy to surrender power to an East Pakistani politician. The President of Pakistan, General Yahya Khan, initially delayed the inauguration of the National Assembly. Later, in March 1971, he banned the Awami League, arrested Bangabandu, transported him to West Pakistan and imprisoned him.

Riots and protests broke out in East Pakistan. General Yahya Khan ordered the Pakistan Army, then predominantly officered by West Pakistanis, to come down on the East Pakistani protestors, with a heavy hand. Within weeks, there were reports of pillage and refugees began arriving at India’s borders in droves. At its peak, there were an estimated 10 million refugees, at India’s Eastern borders.

India was a poor country and could barely manage the refugee crisis, which involved providing food, shelter and medical treatment to the refugees. India appealed to the international community for assistance; however, very little assistance was forthcoming.

The Cold War and South Asian Geopolitics

At that time, the Cold War between the United States (US) and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was at its peak. The then the US Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, was wooing Chairman Mao Tse-tung of the Peoples Republic of China (PRC) to counter Russian influence. India was the leader of the non-aligned movement, while Pakistan was firmly allied with the US. To make matters worse, President Yahya Khan was a personal friend of US President Richard Nixon. When no international assistance was forthcoming, advisors in India’s security establishment pointed out to the Indian PM that it may be cheaper to wage war on Pakistan and create a new state for East Pakistan rather than continue maintaining 10 million refugees indefinitely. US and China made their positions clear - India would be ill-advised to take military action and in the event of war, both powers would openly support Pakistan. At that point of time, it appeared that India was isolated internationally and the 10 million refugees on her borders, would receive no international assistance.

A Strategic Treaty

In August 1971, with little fanfare, it was announced that India had entered into an accord with the USSR. Called the Indo–Soviet Peace Cooperation and Friendship Treaty, it provided India with the confidence to wage war, if necessary. Written in diplomatic language, it contained two articles of special interest. The first stated that the two countries would not enter into alliances with other countries that were inimical to either. The second stated that if either country were to face a threat, the two countries would meet and decide measures to remove that threat.

On 03 Dec 1971, Pakistan Air Force launched a pre-emptive airstrike on Indian Air Force bases in the Western Theatre and India and Pakistan were at war. In the Eastern Theatre, the Indian Army advanced on multiple thrust lines, converging on Dacca. As the war progressed, it soon became apparent that India was likely to secure a major victory and Pakistan was likely to be balkanized. The US Ambassador to the United Nations (UN) was George H W Bush Sr., who would later become President of the US. He introduced a resolution in the UN Security Council, demanding that India and Pakistan stop all military operations forthwith and, all military forces withdraw to the international border. If India were to comply with such a resolution, it would mean wasting the war efforts and continuing to hold 10 million refugees. The strategic treaty was put to the test and the USSR exercised its veto on the resolution. Under the UN charter, only the P5 (United States, United Kingdom, China, France and USSR) have the privilege of veto. However, diplomatic pressures make it difficult for a P5 nation to exercise the veto. The USSR let India know that it would not use the veto indefinitely and gave India 14 days to complete the operations.

As Indian forces built up around Dacca, USA dispatched their aircraft carrier group, ‘USS Enterprise’, to the Bay of Bengal. The UK sent their aircraft carrier, ‘HMS Eagle’, to join the US flotilla. The USSR dispatched two separate naval convoys from their Port at Vladivostok comprising frigates, destroyers and at least one nuclear submarine. The Russian warships joined the US and UK warships in the Bay of Bengal. One might imagine that while the Indian Armed Forces were closing the noose around Dacca, there was a major stand-off between superpowers, in the Bay of Bengal.

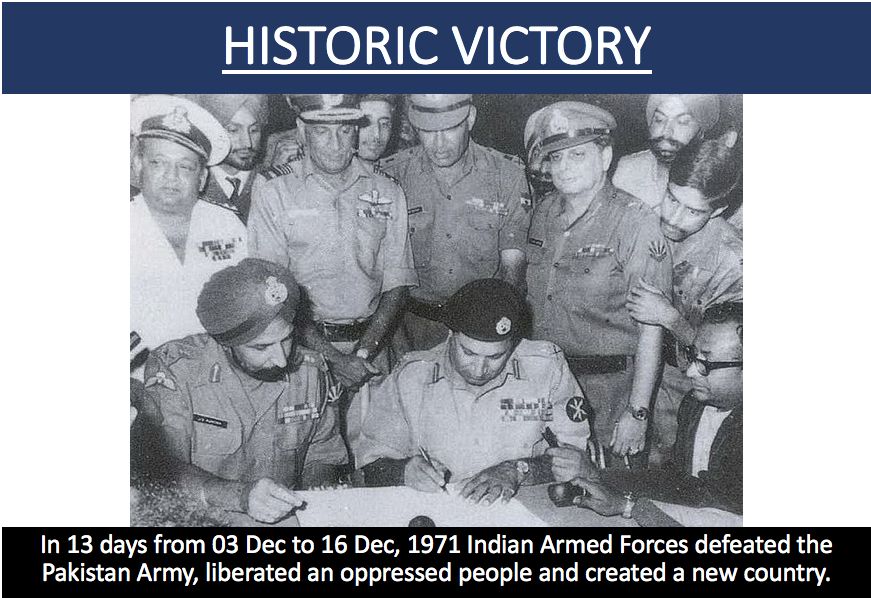

The stand-off paid dividends: on 16 Dec 1971, Lt Gen AAK Niazi surrendered to the Indian Army, with approximately 93,000 Pakistani soldiers. It was a historic victory and the largest surrender of troops, after the 2nd World War. The new and independent nation of Bangladesh was born, and the geopolitics of the subcontinent were changed forever.

Lessons For Corporates

From the point of view of ‘daring to disrupt’, the Indian PM showed exceptional courage, in forging the alliance with the USSR. However, in making that decision, she sacrificed India’s traditional and principled non-aligned diplomatic position. It should be appreciated that when she took the decision, there would have been opposition from India’s diplomats.

Thus, when one dares to disrupt, one should be a risk-taker and also be prepared to make prudent sacrifices.

A friendship treaty was no guarantee that the Soviet Union would exercise the veto and continue to do so until India was victorious. If a UN resolution had been passed, India may have been compelled to halt military operations. As a result, perhaps Bangladesh may never have been created and 10 million refugees may have had to be absorbed in the Indian state.

Being a risk-taker also means that one must be prepared for adverse consequences.

Authored by Major General Moni Chandi (Retd), Chief Strategic Officer, Synergia Foundation

Comments