The Cost of Short-Termism

June 7, 2019 | Expert Insights

The myopia of the salient present

Every now and then, we come across the date, 2100. It’s a milestone year frequently cited not only in science fiction but also in climate change reports and studies on technological disruption. Currently, over 1.3 billion people around the world - nearly 17% of the global population - are under the age of 15 years. With the global average life expectancy of 73 years (85 years in countries like Japan), it would be safe to say that several million people currently under the age of 15 years will live to see the dawn of the 22nd century. By then, medicine may have extended the average lifespan, and perhaps many, even at 81 years, will only be on the cusp of retirement.

But 2100 is so far ahead and overcast with so many possibilities, that it is difficult to see how we may get there. How often do we ever consider that millions of people alive today will be there as 2100 arrives, inheriting the era our generation will leave behind? That all the choices we make today, for better or worse, will be theirs to live with? Are we conscious that these descendants will also have their own families: several hundreds of millions of people not yet born, most of whom we will never meet?

Part of the problem is our obsession with the 'now'. We seem to have collectively revved ourselves into a pathologically short attention span. The trend is perhaps coming from the acceleration of technology, the short-horizon perspective of market-driven economics, the next-election perspective of democracies or just the distractions of personal multi-tasking.

But how do we begin to ingrain this type of Big Picture thinking into our everyday decisions? Let’s take the case of Matthew, a newly elected politician facing a dilemma. He has before him the option of spending a few billion dollars on climate change mitigation, disaster risk management, pandemic preparation and reducing nuclear waste. All of these will be of immense value to Matthew’s great-grandchildren, saving millions of lives and trillions of dollars down the line. But no benefits will be visible in the immediate while there’s a cost to pay. His constituents in the fossil fuel industry need jobs, the military need funding for national security, and he was elected by promising tax cuts.

An economist in Matthew’s office offers a solution pointing to ‘temporal or hyperbolic discounting’, also called ‘social discounting’ - a technique that can be applied to far future benefits such as the ones Matthew is contemplating and that is accepted as standard practice around the world.

Policy-makers use the ‘social discount rate’ in cost-benefit analyses to decide whether to make investments which have an impact in the long-term. The discount rate weighs the benefits for future people against the price that needs to be borne in the present, proposing that the calculated value of benefits to future economies and people should steadily reduce over time. For example, if an expensive sea-bridge to foster trade is being considered, the social discount rate approach will tell you that a 6% boost in economic growth in 12 months is better than a 6% boost in 10 years.

Politicians like Matthew are required to take decisions that affect the long-term, but a looming election can often cloud the foresight which must permeate their actions. Politicians and the people they govern have a tendency to limit what cost they are together willing to bear for the sake of people who do not exist as yet. After the number crunching using a standard social discount rate, Matthew and his economists come to the conclusion that their investments may not show sufficient payback for decades or possibly even centuries. Their cost-benefit analysis thus failing, Matthew takes no immediate action and postpones the decision for his successor to deal with.

Have we evolved for long-term thinking?

Homo sapiens haven’t always had the luxury to think about the long-term, nor the ability to think in an abstract way about it. Our hunter-gatherer ancestors were for most parts preoccupied with mere survival. Today, though, we have the luxury of living in the moment; we can be fully absorbed by music or mentally time-travel to imagine events in the past or scenarios in the future.

Without much effort, we can imagine what we’re going to do tomorrow or next week or where we’re going to have a holiday. We can think up options of what career path to pursue; we can imagine and even evaluate alternative scenarios for each of those.

Scholars like Yuval Noah Harari recognize that our ability to imagine distinct scenarios in the future is a vital adaptation that led to our species’ success. In his book, Sapiens - A Brief History of Humankind, which explores the deep human past, Harari writes:

“You could never convince a monkey to give you a banana by promising him limitless bananas after death in monkey heaven.”

Thus, we have the innate ability to imagine the consequences of our actions in deeper time, but unfortunately, not always the patience, presence, will or motivation to escape the salience of the current.

When faced with complex decision-making, our brains have evolved to employ ‘heuristics’ - mental shortcuts or rule-of-thumb strategies that shorten decision-making time. However, while heuristics - which usually involve focusing on one aspect of a complex problem and ignoring others - can speed up our decision-making process and time, they can introduce errors and biased judgments.

Many of these have to do with how our brains have evolved over millions of years with respect to our ability to think long-term. To understand this better, we now delve into the arena of evolutionary psychology.

In Matthew-the-politician’s case, we saw an example of how human motivation is highly influenced by how imminent the reward is perceived to be - meaning, the further away the reward is, the more we discount its value. This built-in mechanism of our brains is often referred to as present bias, or hyperbolic discounting.

In his book, The Art of Thinking Clearly, Rolf Dobelli, best-selling author and entrepreneur writes:

“Hyperbolic discounting, the fact that immediacy magnetises us, is a remnant of our animal past. Animals will never turn down an instant reward in order to attain more in the future. You can train rats as much as you like; they’re never going to give up a piece of cheese today to get two pieces tomorrow.

Think drugs, tobacco, alcohol, pizza, sitting on the couch or even investing in bad businesses in the expectation of making a quick return – we are all looking for quick fixes – things that make us happy now."

If you were offered the choice of $50 right now or $100 tomorrow, you would probably choose the latter but ‘hyperbolic discounting’ describes how the importance of this extra $50 quickly diminishes for most people as the delay gap widens. For instance, if someone instead asked you to choose between $50 today or $100 in one year, you’re statistically more likely to take the $50 right now, even though the difference in financial gain hasn’t altered.

This devaluing of something that is delayed can be explained by our modern desire for instant gratification. Peter Bevelin, Swedish author and investor, in his masterpiece book, Seeking Wisdom writes:

“We give more weight to the present than to the future. We seek pleasure today at a cost of what may be better in the future. We prefer an immediate reward to a delayed but maybe larger reward. We spend today what we should save for tomorrow. This means that we may pay a high price in the future for a small immediate reward."

Richard Thaler, the Nobel Prize winning economist further redefined how we understand human motivation and decision-making. His groundbreaking research into behavioral economics has upended the concept of homo economicus — the notion that people are completely rational decision-makers — and found that humans are often quite irrational in their economic decisions. In his book, Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness, Thaler along with coauthor, Cass Sunstein, writes:

"People often make poor choices—and look back at them with bafflement!. We do this because as human beings, we all are susceptible to a wide array of routine biases that can lead to an equally wide array of embarrassing blunders in education, personal finance, health care, mortgages and credit cards, happiness, and even the planet itself."

Thus, in a lollapalooza of so many cognitive biases acting in compound with each other and increasing the likelihood of irrational decision-making, it is no wonder that humanity’s big challenges: the looming ecological crisis, the growing threat of weapons of mass destruction, the rise of new disruptive technologies, and our newly found power to reshape and re-engineer life - all feel so hard to tackle right now.

“The destiny of our species is shaped by the imperatives of survival on six distinct time scales. To survive means to compete successfully on all six time scales. But the unit of survival is different at each of the six time scales. On a time scale of years, the unit is the individual. On a time scale of decades, the unit is the family. On a time scale of centuries, the unit is the tribe or nation. On a time scale of millennia, the unit is the culture. On a time scale of tens of millennia, the unit is the species. On a time scale of eons, the unit is the whole web of life on our planet.

Every human being is the product of adaptation to the demands of all six time scales. That is why conflicting loyalties are deep in our nature. In order to survive, we have needed to be loyal to ourselves, to our families, to our tribes, to our cultures, to our species, to our planet.

If our psychological impulses are complicated, it is because they were shaped by complicated and conflicting demands.”

- Mathematician and physicist, Freeman Dyson.

The power of incentive systems

Investor, Esther Dyson, once said,

“In politics the dominant time frame is a term of office, in fashion and culture, it’s a season; for corporations, it’s a quarter, on the internet it’s minutes, and on the financial markets, mere milliseconds."

Short-termism receives an impetus from the way our incentive systems are lined up. In the case of Matthew-the-politician, although he knew that authorizing the required funding for climate change mitigation, disaster risk management, pandemic preparation and reducing nuclear waste would save millions of lives and trillions of dollars down the line and be of enormous value to his great-grandchildren, he was more drawn by his short-term motive to showcase the tangible outcomes of his decisions before the end of his tenure. Noting that there would be no benefits visible in the immediate while there would be a cost to pay, he eventually chose not to act.

“First, incentives are not properly aligned. If you engage in environmentally costly behavior next year, through your consumption choices, you will probably pay nothing for the environmental harms that you inflict.” - Richard H. Thaler, Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness

Similarly, in financial markets, the problem of incentives has been fundamental to economics. As seen in several cycles of financial destruction, perverse, short-term incentives for market practitioners being far removed from the best interests of investors, they not only encourage decision makers to ignore high-yielding, long-term opportunities, but also invite individual and institutional corruption.

Warren Buffett, arguably one of the greatest investors of all time, has demonstrated the benefits of taking the long view in the financial markets. Interestingly, an analysis by UBS Wealth Management for the period, January 1988 to March 2019, showed that Buffett oftentimes underperformed the market. However, his outperformance over the entire period: 350 percent.

Unfortunately, in the current climate of short-termism and the demand for immediate results, Buffett would barely last in the business if he didn’t already have his reputation. Indeed, an investor with a rear-view mirror that only looks back one quarter would find the Warren Buffett experience mediocre at best.

Buffett doesn’t dwell on his company’s short-term performance and has long preached about the importance of long-range thinking. He, along with J.P. Morgan Chase CEO, Jamie Dimon, recently floated the idea of ending the corporate practice of providing quarterly guidance to investors.

Are we colonizing the future?

Social philosopher, Roman Krznaric, speaks about our tendency to treat the future like a distant military outpost, devoid of inhabitants, where we can freely dump ecological waste, technological risk, nuclear waste and public debt. We feel at liberty to plunder it as we please, he points out.

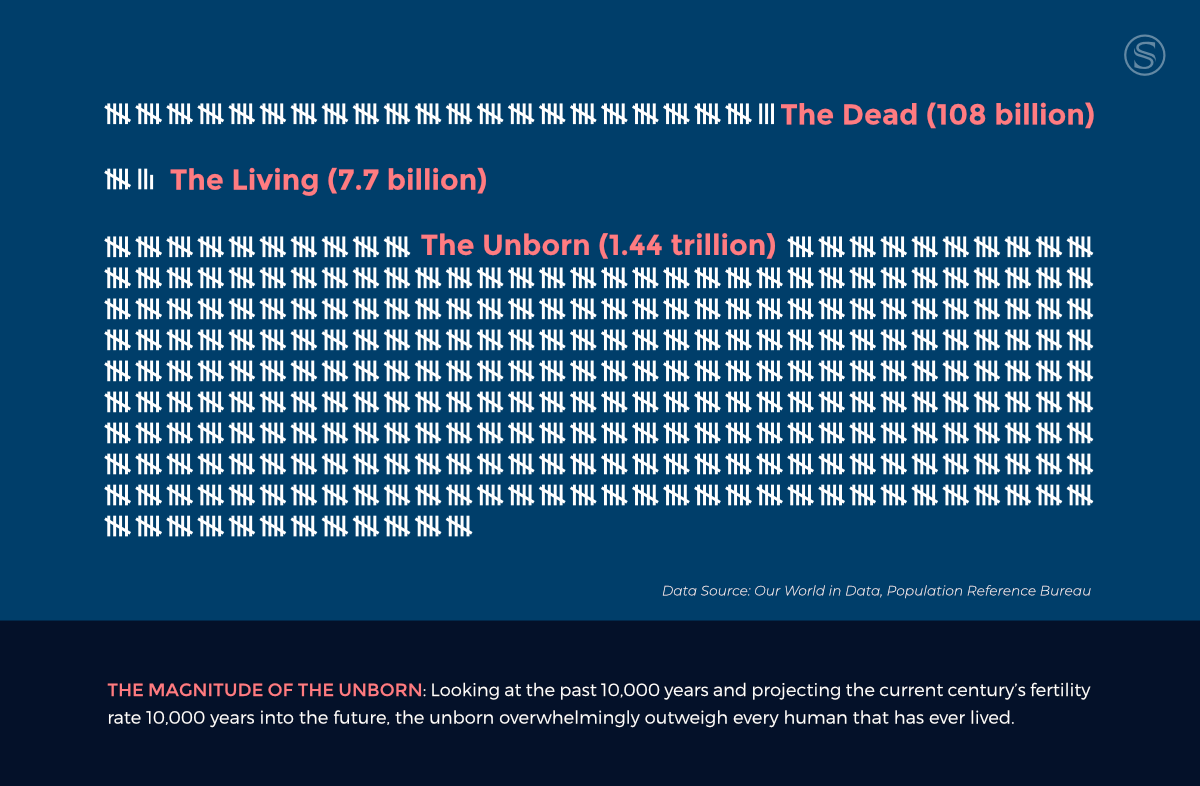

Today’s population of 7.7 billion is a lot, but it is small when we weigh it against the number of unborn people. If we look at the past 10,000 years and for the sake of illustration, project the current century’s fertility rate of 1.93 children per woman 10,000 years into the deep future, the population of the unborn would be about 1.44 trillion: the unborn outweigh every human that has ever lived.

Considering the possibility that our species survives for tens or hundreds of thousands of years, that adds up to trillions of families and relationships, amounting to numerous moments of potential joy, tenderness and love.

It is far too easy to be self-congratulatory about how much less prejudiced we are than previous generations. While the racism of the 1950s looks terrible today, we must ask ourselves - are we really so progressive? It would be far more pertinent to ask how our generation would be looked back on; what might our own descendants deplore about us that we take for granted.

Terra nullius, a Latin expression meaning 'nobody's land', is a principle used in international law to justify claims that territory may be acquired by a state's occupation of it. Under this law, ownership rights of indigenous Aborigines of Australia were ignored in the British settlement of Australia in the 1700-1800s. In a similar 'terra nullius' attitude, by failing to value the lives of our descendants, are we ‘colonising’ the future?

Amidst an increasingly salient present, with contemporary moments dominating our thoughts and agendas and short-termism dictating our behaviours and decisions, we experience a type of exhaustion that prevents deep, forward-looking thinking. Writing in 1978, Elise Bounding, a noted sociologist, called it ‘temporal exhaustion’, where one is mentally exhausted all the time from dealing with the present and there is no energy left to imagine the future.

Our acts of neglect or stupidity, driven by the salient present, threatens the lives of our descendants and civilisation itself. And yet, things don't have to be all gloom and doom, if only we rise above the all-pervading short-termism and pepper our decisions, big and small, with the one question: How can we be good ancestors.

---------------------------------------------

The author is Christabel Singh. Specializing in future trends and long-range planning, she is particularly interested in the long-term view of humanity and our impact on future generations. Christabel is a Research Associate at the Synergia Foundation.

Submitted by Lakshmi (not verified) on Sat, 06/08/2019 - 07:39

Very nice article. makes us