West Africa: Democratisation in Peril?

October 11, 2021 | Expert Insights

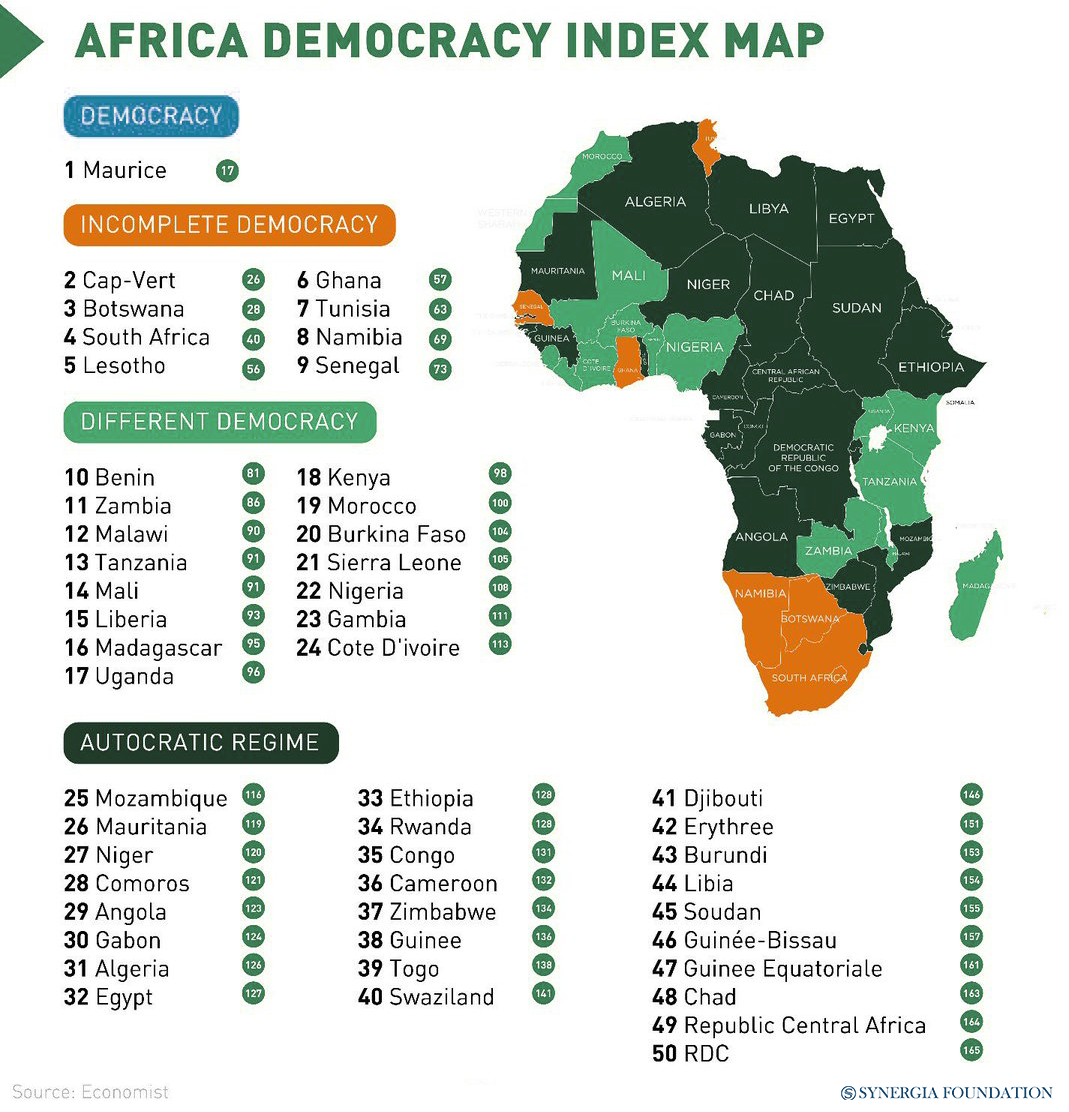

In the wake of a military coup that overthrew Guinea's civilian leader, Colonel Mamady Doumbouya has been sworn in as the interim President of the country. In doing so, he becomes the latest leader in West Africa to seize power unconstitutionally. Earlier this year, Mali and Chad had also witnessed similar regime changes, sparking fears of backsliding of democracy in this politically volatile region.

Background

West Africa is no stranger to military putsches, especially in the post-colonial era. Reports indicate that the countries in the sub-region had witnessed at least 44 successful coups from Independence to 2004. In 1999, however, when regional heavyweight Nigeria had transitioned from military to civilian rule, it gave rise to widespread optimism that the era of unconstitutional regime changes would finally come to an end. At that point, transparent elections and regular leadership transitions, in accordance with constitutional provisions, were actively encouraged by regional groups like the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS).

In recent years, however, this trend appears to have been reversed, with power grabs in Chad, Mali and Guinea. Attempted coups in Nigeria and Sudan have also dominated global headlines.

Analysis

The democratic decline in West Africa had been discernible much before the tumultuous events in Chad, Mali, and Guinea. For instance, in 2018, Senegal had enacted controversial laws that imposed limits on candidates who could stand for elections. Around the same time, the government in Benin had been accused of orchestrating politically motivated prosecutions against the opposition. Even Nigeria was caught in the eye of a political storm when national and regional elections in the country were reported to have irregularities, and the President rejected proposals for electoral reforms.

As many such countries in the region became embroiled in their own political crises, there were increasing protests against the incumbent civilian leaders. This proved to be a veritable opportunity for military doyens to grab power, citing the dubious legitimacy of the previous heads of state. A case in point is Guinea, where former President Alpha Condé was accused of holding an illegal referendum to secure his third term in office. Sensing that the public opinion had turned against him, Colonel Doumbouya was able to launch a coup d'état, asserting that he would now ‘entrust politics to the people.’

Although such coups are far from the social revolutions they claim to be, the international community cannot afford to ignore their underlying causes. Ruling elites in the region are often isolated from the people they are expected to govern, with corruption and clientelism remaining a pervasive problem. Moreover, regional groups like ECOWAS and anchor states like Nigeria are perceived to be not doing enough to promote democracy in the region. For example, the West African regional bloc had allowed Conde to seek a third term in Guinea without many protestations, even though there were debates about a two-term limit on presidential mandates.

Meanwhile, Western countries have often been hesitant to condemn electoral malpractices or other civil liberty restrictions in these nations, as their cooperation is critical to tackling terrorists and other armed extremist groups. More importantly, they are critical economic partners in offsetting the growing ambitions of China and Russia in the region, apart from stemming migration flows.

For the same reasons, it remains to be seen if regional bodies and international partners take strict action against the new military regimes in Guinea, Mali, and Chad. Of course, with respect to Guinea, both the ECOWAS and the African Union have already suspended the country’s membership. The former regional bloc has also imposed sanctions against the coup leaders. Similarly, Mali has been suspended from ECOWAS, apart from being sanctioned by the U.S. The worry, however, is that such punitive measures may be eventually eased to accommodate other strategic and economic priorities that arise, a fact well-known to the current coup leaders.

Meanwhile, in Chad, the new regime has been supported by France and the African Union, despite the blatantly unconstitutional transfer of power. Such ‘double standards’ will not go unnoticed by other aspirants in the region, who may be tempted to make their own bid for power.

Assessment

- Undemocratic countries can be unreliable partners in addressing political instability, corruption, migration flows and violent extremism. Therefore, international allies should demonstrate the political resolve to hold the new regimes to account, despite their vested interests. Any failure to match strategic and economic priorities with support for democratic frameworks will be a myopic move.

- Regional bodies like ECOWAS need to exert sustained pressure on the current military regimes to put a transition plan in place. Based on the inputs of local and international stakeholders, there should be clearly defined timelines for the conduct of elections. Moreover, military leaders should not be afforded the opportunity to reposition themselves as civilian candidates. Unless these objectives are realised, West Africa will continue to remain a breeding ground for ‘coup plotters’.

Comments