WATER WARS: COOPERATION OR CONFLICT?

July 16, 2022 | Expert Insights

Water has always been the lifeblood of all civilisations. One of the world's earliest civilisations-the Indus Valley- originated along the course of the Indus River, marking the rise and fall of great civilisations. The vast fertile fields nourished by the great rivers of the Indian subcontinent ensured enough food supply to its inhabitants for centuries leading to a population density that is perhaps the highest on the planet. As long as water flows from the perennial melt of Himalayan glaciers, supplemented by ample monsoon rains, the subcontinent will be self-sufficient in food. The danger lies in the water sources drying up due to rising temperatures and climate changes which disrupt the annual monsoons. Bereft of water, the fertile plains of South Asia will become death traps for its teeming millions.

Incredulously, a war in far-off eastern Europe threatens to choke off the food supply of a significant part of the world, adding to the economic and humanitarian desolation after two years of a devastating pandemic. If rains fail and the glacial melt drastically reduces in the immediate future, a possibility that is not that unlikely, South Asia in its entirety faces a calamity of gigantic proportions. A region that is notoriously contentious and unwilling to make concessions for the common good faces a real threat from water scarcity. The outcome can be conflict, famines, anarchy- in brief, political and economic catastrophe at a scale that can scarcely be imagined.

Background

The Covid-19 outbreak redirected attention from conventional security threats to non-traditional security threats, particularly human security. In their efforts to recover from the after-effects of the pandemic, the fragile economies of South Asia are now facing fresh headwinds from high inflation, expanding fiscal deficits, and deteriorating current account balances. However, South Asian nations can ill afford to overlook the water shortage as it impacts nearly all aspects of sustainable development. Competition to secure the largest share of the water resources is no longer an option; the dwindling waters of rivers have to be shared in an equitable manner for which nations must collaborate and cooperate.

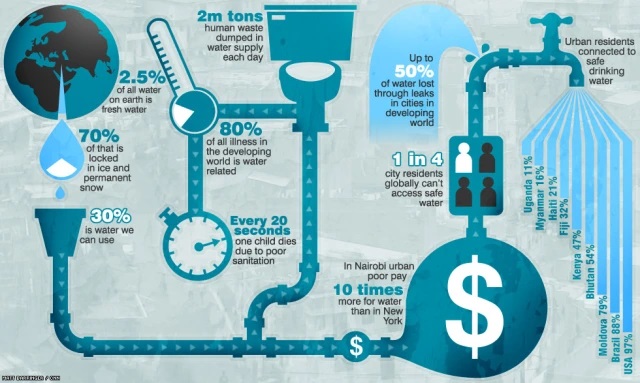

On the waterfront, the problems are numerous- scarcity of clean drinking water, poisoned and over-exploited groundwater, unequal distribution of limited water supply and poor rainwater management leading to vast quantities running off into the ocean.

A Chatham House report titled “Attitudes to Water in South Asia” highlights the linkages between water, energy, and food. In India, decades of subsidised / free electricity for farmers led to farmers indiscriminately exhausting groundwater beyond its capacity to replenish itself. As per data available on the net, 65 per cent of India's irrigation reequipment is met by groundwater. The interaction between water and energy is viewed in Nepal and Pakistan through the lens of unrealised hydropower potential. To make matters worse, most rivers are either drying up or are polluted. Increasing population coupled with climate change have all put immense pressure on water resources. Compared to most other nations, South Asian countries’ dam storage capacity is highly insufficient for its irrigation. When contrasted to United States' 900 days, South Africa's 500 days, India's 120–220 days, and Pakistan's storage capacity is approximately 30 days. Moreover, as per capita water availability continues to decline and demand for food production rises, the region will also be battling to attain food security for all

The region is dominated by major transboundary rivers such as Brahmaputra, Indus, and Ganges. Sadly, transboundary water issues have fuelled tensions and have become intrinsically linked to national security, making any collaboration politically incomprehensible. Conspiracy theories abound; Afghanistan accuses Pakistan and Iran of being responsible for its water woes, while Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Nepal point fingers at India, and India blames China for damming the great rivers that rise from the Chinese water basin.

Let us take the case of Pakistan, which is heading towards a major water crisis. According to a report published by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and Pakistan Council of Research in Water Resources (PCRWR), the country by 2025 will be facing a “severe water shortage”. Pakistan is still a long way from recognising the situation, let alone addressing it. The country is said to have fallen out of the “water stress line” as early as 1990 and later crossed the water scarcity line in 2005[1]. The amount of water per capita availability has reduced drastically from 5600 cubic meters in 1947 to 908 cubic meters in 2017. Currently, water availability is 866 cubic per capita in 2020.

Analysis

Enduring food security in South Asia is a real challenge for all the nations of the region. The World Food Programme reported that even today, 20.5 per cent of the population is undernourished, and 44 per cent of children under five are stunted. Food insecurity in any country can be experienced for several reasons, but the trend in South Asian nations is caused by high inflation, worsening climatic conditions, inadequate infrastructure, and mismanagement of water. Additionally, the Ukraine crisis has resulted in food supply chain disruptions impacting beyond borders.

Assessment

- In the area of cooperation, there is a lot of scope for collaborative research and development among South Asian nations; again, it can be achieved only when there is a political will to do so. The case of exemplar cooperation is depicted in the Indus water treaty between India and Pakistan. It must not be forgotten that the treaty has withstood three wars, and other hostilities, demonstrating the will for compromise and cooperation for the betterment of the future.

- Likewise, is the successful basin-sharing of Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna between India and Bhutan. This has stimulated improvement in the quality of life in both the countries through income generation and poverty alleviation.

- Overall, strengthening regional trade cooperation and building regional governance institutions can unlock long-term growth in the region.

Comments