Shrinking Labour Pool

June 8, 2021 | Expert Insights

Portending grim socio-economic challenges, China’s population has grown at its slowest pace since the 1960s. According to the 2020 census, the average annual growth rate over the last decade was 0.53%, which is 0.04% less than the figures recorded between 2000 and 2010. Although the population levels have not declined in absolute terms, experts indicate that this will soon come to pass, as current fertility rates are not sufficient to replace a rapidly-ageing population. If this is indeed true, it would be the first demographic decline since the 1960s, when millions of people had succumbed to the great Chinese famine.

Policymakers are concerned that a diminution of the population could retard China’s drive to achieve the average household wealth matching developed nations. In fact, speculations are rife that the Chinese government delayed its publication of the Seventh National Population Census to avoid such ominous forecasts. Having released this data, however, the Communist Party has paved the way for an aggressive rollout of measures that seek to reverse demographic trends. It remains to be seen whether this will be sufficient to tide over the effects of what is essentially a self-inflicted crisis.

FAMILY PLANNING POLICIES

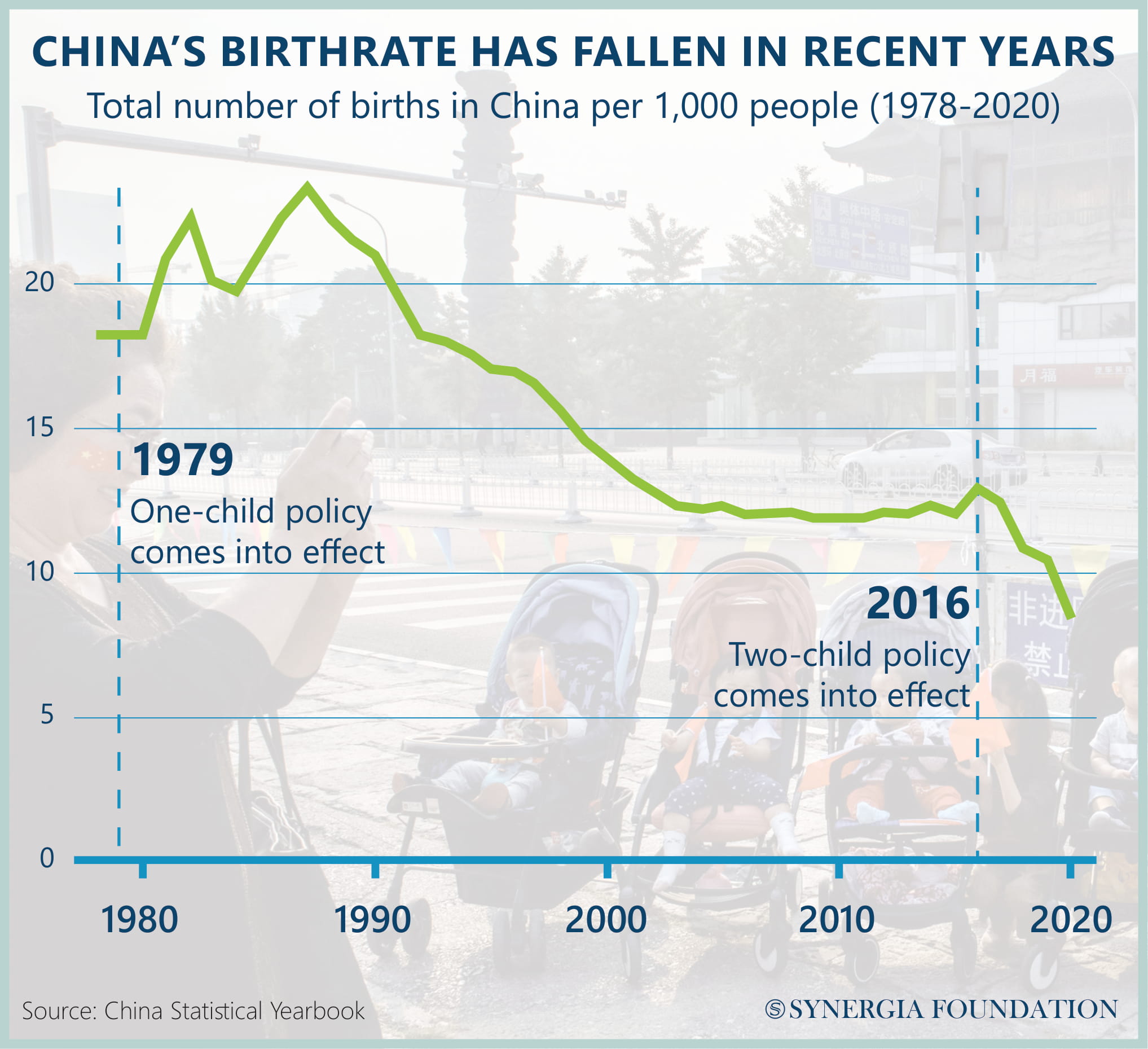

The source of China’s demographic woes can be traced to the 1979 era ‘one-child policy’, which had imposed a harsh ‘single child’ norm to reduce its massive population growth. Violators of this policy had been faced with the prospect of fines, loss of employment or even forced abortions. While this heavy-handed approach may have slowed down the population growth in this country, it simultaneously contributed to a reduction in the number of women of child-bearing age. Between 2000 and 2010, UN demographers estimate that the fertility rates had dropped to 1.6 births during the average lifetime of a woman. As this trend continued, the number of new births proved insufficient to replace the steadily burgeoning population of elderly citizens as well as the deceased.

SOCIO-ECONOMIC FALLOUT

With a progressively diminishing pool of young people, there has been a relative stagnation in China’s labour force. A research paper circulated by the People’s Bank of China warns that the benefits of a large working-age population, which the country has hitherto enjoyed, will taper out soon. Any resultant increase in labour shortages, therefore, will trigger wage inflation. Since China’s export-oriented economy relies on inexhaustibly cheap labour, it can affect factory productivity, thereby undermining the demographic dividends that the region has long boasted of.

A shrinking workforce can also aggravate the inverted age structure, with not enough young people to support the social welfare costs of senior citizens. Certain studies suggest that China will transition from having eight workers for each retiree to two workers for each retiree by 2050. Against this backdrop, demands for healthcare and pensions are likely to spike, with an ever-increasing number of retirees triggering a national reallocation of priorities. Such diversion of resources away from investment and production may hamper economic growth, as has been witnessed in the case of Japan. Although the Chinese State has adequate cash to cover pensions at present, analysts fear a looming debt crisis in the foreseeable. In fact, the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences has estimated that the pension reserve may run out by 2035. Already, shortfalls have been reported in the North-Eastern province of Heilongjiang, where authorities are being compelled to establish a national pool and cross- province allocation of funds to make up for the pension deficit.

Anticipating such a crisis, many leaders in the Communist Party have called for an increase in the retirement ages of workers to reduce the gap between contributions and outlays. Indeed, this proposal has been vaguely incorporated in a new five-year plan. Sceptics, however, point out that the lengthening of work lives can further drive down fertility rates, as many families in China rely on their elderly members to take care of their children.

Finally, there are concerns that domestic consumption may be adversely affected, as most economies are driven by the consumer appetites of a young demography. From purchasing property to buying consumables, they are more prone to adding new goods to the consumption basket. If such spending patterns are not sustained, then the rate of investment will be inadequate to fuel growth.

OFFSETTING DISADVANTAGES

Acknowledging these problems, the Chinese government had ended its controversial one-child policy in 2016 and allowed couples to have two children. This, however, failed to reverse the country’s falling birth rate in the short term as urban couples, caught in a web of consumption, were loath to spend more money on raising children at the cost of their own lifestyle. Given this reality, policymakers are said to be considering the possibility of extending cash payments or providing cheap child- care as an incentive. There are also calls for a radical revamping of China’s family planning policy.

Most recently, the government has succumbed to demographic pressures, by further lifting the cap on births and permitting couples to have three children. Only time will tell whether these measures can dispel the spectre of past policy errors. In the meantime, Beijing has scaled up its investments in technological resources to overcome demographic problems. By switching to a highly automated and flexible manufacturing process as well as establishing its superiority in robotics and artificial intelligence, it hopes to move up the global value chain. This, in turn, can offset any apparent disadvantages in labour costs and workforce numbers. As remarked by Paul Chan Poh Hoi in the Straits Times (May 17, 2021), age becomes less of a factor in a knowledge-driven economy.

Assessment

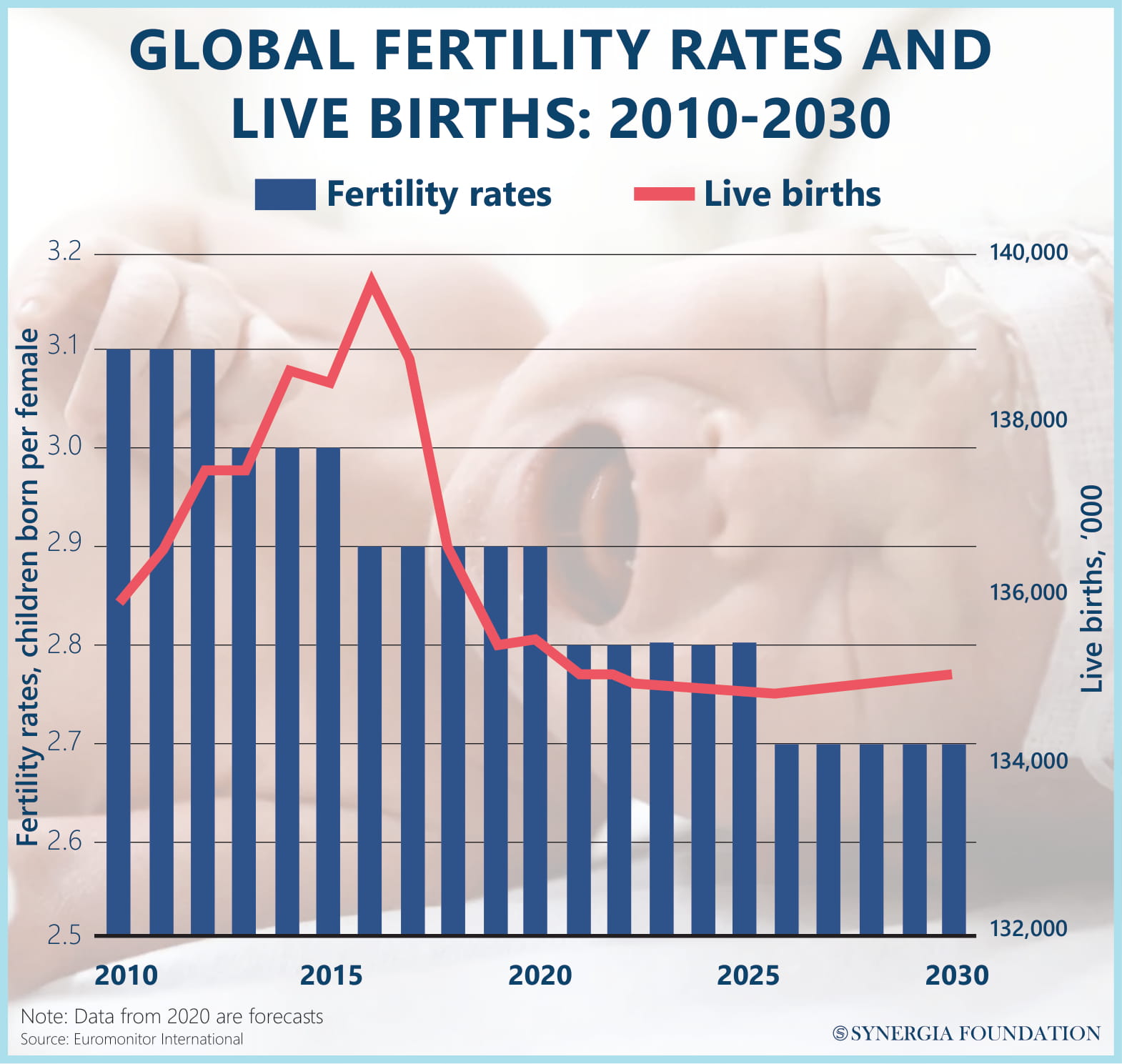

- China is not the only nation suffering from a drop in fertility levels. Japan, South Korea, the U.S. and the European Union have also recorded falling birth rates. However, unlike their Western counterparts, these Asian countries have a closed immigration system. Therefore, they may be not able to counterbalance their demographic shortcomings with mass migration flows from the Global South, as has been witnessed in Europe and North America. Contrary to xenophobic rhetoric, an influx of refugees can contribute to the economic dynamism of Western countries.

- The falling birth rate is a natural by-product of economic development and prosperity. Although Japan and South Korea have faced identical predicaments, they have met them with first-class infrastructure, education systems and high-tech supply chains that continue to bring prosperity. In any case, manufacturing processes that are based on cheap and easily available labour cannot last forever. It is inevitable that they will replaced by smart factories that employ fewer workers. Therefore, the global consumer has to be prepared to pay for this change.

Comments