Seeking a 'holy Alliance'

November 10, 2020 | Expert Insights

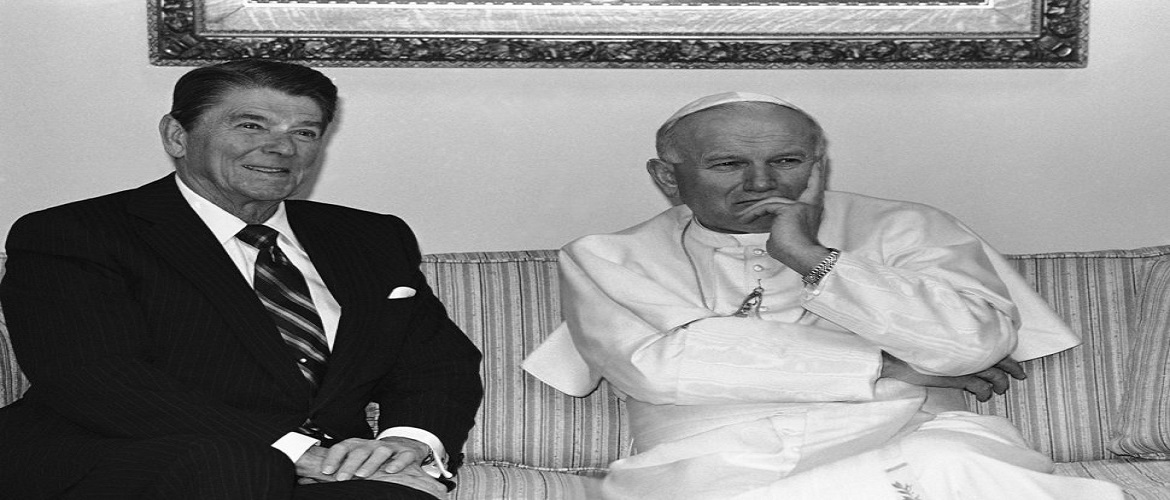

China’s rise as a global player has undoubtedly shaken the established world order and forced countries to revisit their strategies. The Vatican, historically a power broker between the great empires of the Western world, has seldom refrained from engaging in its own geopolitical manoeuvres. Its discreet, yet powerful evocation of religious ties within a largely Catholic Poland in the 1980s is considered by many as a trigger for the implosion which brought down the Soviet Union. As pointed out by former American diplomat and military professor Patrick Mendis, President Ronald Reagan had enlisted the moral authority of the Vatican to undermine the Polish regime and other communist-bloc countries in Eastern Europe.

Clearly, the Vatican’s capacity to practice realpolitik, albeit in the livery of soft power, is well-documented. There were signs that the U.S. would endeavour to challenge China’s global dominance by replicating this playbook. U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, in a flurry of visits to the Vatican, tried to woo top Vatican officials, urging them to denounce China’s ‘horrific persecution’ of religious believers.

In the instant case, however, the Vatican has been far more circumspect. Pope Francis has not only maintained a deafening silence on issues implicating China (including the treatment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang province), but he has also renewed the 2018 Sino-Vatican accord that allows Chinese officials to appoint Catholic bishops. Evidently, the factors which defined the Soviet-Papal relationship from the 1970s to 1980s are markedly different from the current Sino-Vatican exchanges.

PAPAL PUSH IN THE COLD WAR

As can be recalled, Pope John Paul II, in a historic visit to Poland in 1979, had made an eloquent appeal for religious freedom. The visit had coincided with a disarray in the ranks of Polish dissidents, brought about by efforts of the Moscow-backed Communist regime in Warsaw.

With the papal visit, the dispirited popular movement was galvanised, drawing millions of people out on the streets. The Pope’s reference to a ‘revolution of the spirit’ and ‘freedom of conscience’ acted as a clarion call to unite the now-famous Polish Solidarity movement under Lech Walesa, which went on to dismantle the communist regime in Poland and trigger a domino effect in the rest of the Soviet empire.

HOLY ALLIANCE

It has always been speculated that the role played by the Holy See in Poland was part of a larger U.S.-Vatican strategy. During the Carter Administration, the national security advisor had begun an official dialogue with Papal emissaries, in which Poland and the nascent Solidarity movement figured prominently. This dialogue had then intensified under President Reagan who realised the potential of a ‘holy alliance’ with the Vatican. Official diplomatic relations with the Vatican was re-established, and confidential information was shared through cabinet members as well as the CIA Director.

In a similar vein, the outgoing Trump administration appeared eager to employ this strategy against China. The aim was to invoke the authority of the Pope to undermine the moral legitimacy of China. The Vatican was valued as a strategic partner, as it was the only remaining European state with official diplomatic ties to Taiwan. Since China staked claim to this self-ruled island as part of its ‘One China’ policy, it was important for the U.S. to ensure that the Vatican was on its side.

However, the Vatican’s response was guarded. The Holy See declined to meet with Mr Pompeo on the grounds that political figures are not received ahead of elections.

AN INFORMED PERSPECTIVE

A strategy to exert the influence of the Vatican in geopolitics must be based on a thorough understanding of history and a clear appreciation of ground realities.

The action of John Paul II in 1979 had been deeply grounded in his Polish identity. His being the first Polish Pope ever had carried considerable heft in a country that was predominantly Catholic. This is in stark contrast to present-day China.

Although the Vatican, under Pope Francis, has been making overtures to the Global South, away from its traditional moorings in North America and Europe, this has not translated into a meaningful presence in China. Official diplomatic relations have been suspended since 1951. Out of a population of nearly 1.4 billion, only 12 million are estimated to be Catholics. Even this relatively small community is split between a ‘Patriotic’ church whose clergy is appointed by the Chinese state and a clandestine ‘Underground’ church which remains loyal to the Pope.

Despite a slight thaw in Sino-Vatican ties after the signing of the 2018 accord, there has been no let-up in the harassment and detention of Catholics in China. Shutting down of churches and increased surveillance continue to be the norm. In this context, the Vatican has been treading cautiously with China. Far from contemplating a ‘holy alliance’ with the U.S., its policy mirrors the cold war doctrine of ‘Ostpolitik’, which was preferred by the predecessor of Pope John Paul II. Just as the Vatican, under Pope Paul VI, had tried to foster ties with Soviet-bloc countries to improve the condition of Catholic churches, Pope Francis is attempting the same in China.

Besides, the Vatican was, at best, a catalyst in the disintegration of the Soviet Union. There were other factors that came together to sound its death knell. This includes the U.S.S.R.’s failed military campaign in Afghanistan and the internal discord caused by Mikhail Gorbachev’s Glasnost and Perestroika reforms. Moreover, as the communists had failed to adequately respond to financial hardships in Poland, the capitalist West had started to emerge as a more attractive model then.

Modern-day China is hardly comparable to the U.S.S.R. of yore. Despite a mutually damaging trade war with the U.S. and the impact of COVID-19, it continues to be an economic giant. Whilethe rest of the world is struggling to claw its way out of a slump, China is the only economy to show positive growth in 2020. Therefore, all circumstances considered, the US will find it difficult to repeat history by involving the Vatican in its geopolitics with China.

ASSESSMENT

- The historical circumstances that brought together Pope John Paul II and Ronald Reagan are considerably different from the geopolitical realities of today. As a result, replicating the Polish model remains difficult, if not impossible. Although the President elect Joe Biden, as the second practicing Roman Catholic President after John F Kennedy, may find common ground with Pope Francis on several issues, the Sino-Vatican accord is likely to stay a sticking point.

- The Vatican has limited leverage over China, which views even the appointment of bishops as an infringement of its sovereignty. Fearing draconian measures and the Sinicization of Catholics, the Vatican will be extremely wary of antagonising China.

- President Xi Jinping is unlikely to be overly influenced by a Vatican move in support of its Taiwanese flock, especially if he makes a call to unify the island state through a force of arms. No moral or political position adopted by the Vatican can prevent such an eventuality.

Comments