Round One!

April 24, 2022 | Expert Insights

The inconclusive results in the French presidential elections held on April 10th have led to a second round, as is the electoral norm in France. In fact, it was a replay of the 2017 elections when both Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen had been the leaders in the first round, having failed to secure a clear victory in the opening round.

Background

French presidential voting happens in a two-round system, unlike most other western countries but observed in a few countries in Africa, South America and Central Asia. In the first round, multiple candidates run for the elections; if none of the candidates can win a majority of the vote (more than 50 per cent), then the election moves over to the second round. Only the top two candidates can qualify for the second round of elections, and the winner of this round gets to wear the presidential crown.

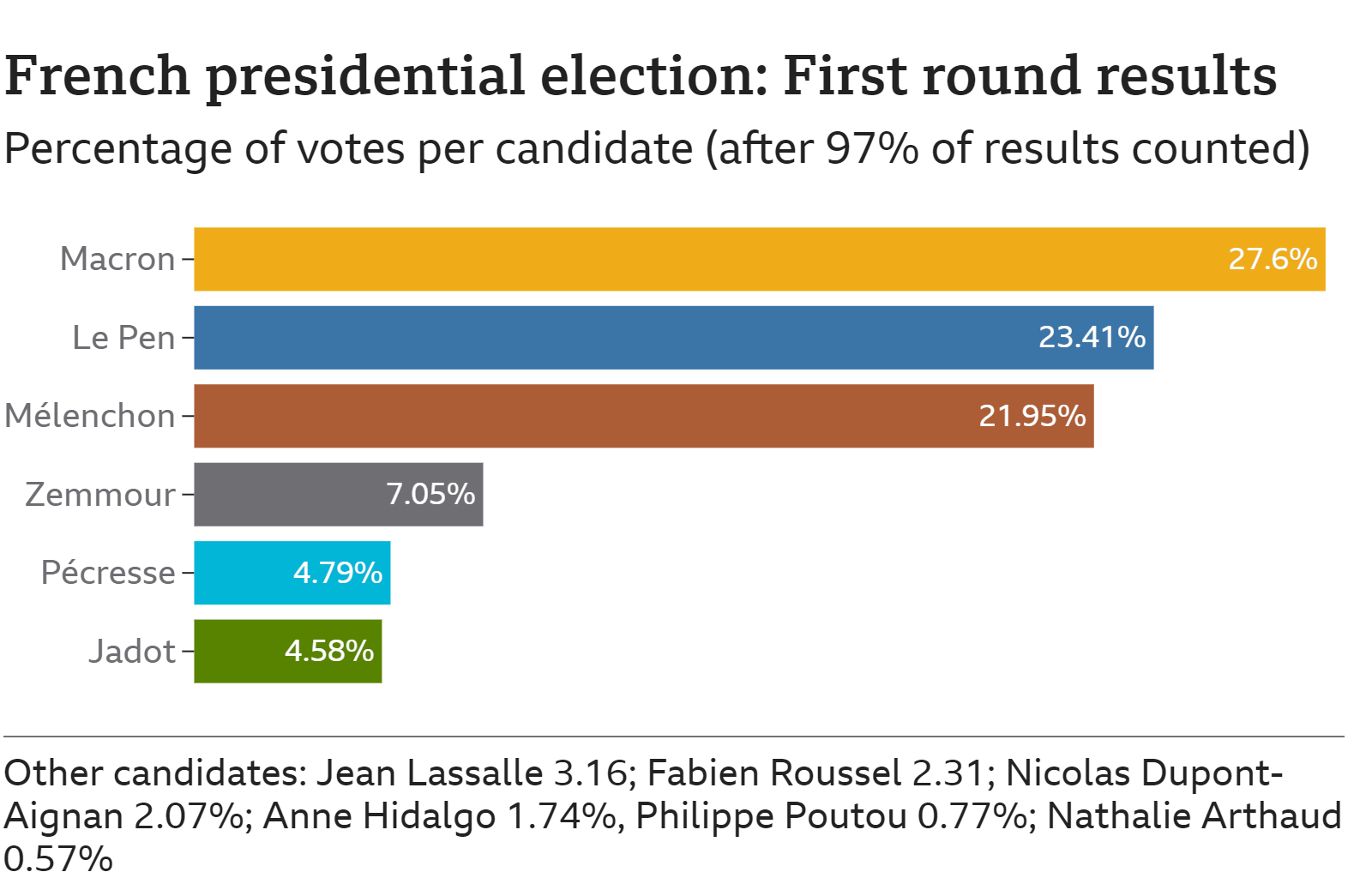

A total of 12 candidates stood in the 2022 election; as expected, no one won a majority of the vote. As was the case in the last presidential elections, this time again, the top two candidates were Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen. Back in 2017, Macron was able to easily win the second round securing about 66 per cent of the vote compared to Le Pen’s 34 per cent. However, this race is expected to be a lot closer.

Analysis

The outcome of the elections is being closely watched as it will have a far-reaching effect. It will decide if, in the current charged atmosphere of Europe, a far-right revival will once again take place. Marine Le Pen, who won 23.1 per cent of the vote in the first round (roughly equal to 8.1 million votes), is from the National Rally, formerly known as the National Front, a far-right political party founded back in 1972. From 1972 to 2011, its leader was Jean Marie Le Pen; Marine Le Pen took over the position from her father in 2011 and has since led the party.

The National Rally has been variously described as far-right, neo-fascist and a populist party. Being a fringe party of the French political in the 1970s, it clawed its way to prominence in the 1980s, making significant inroads into French politics. But its influence declined in the early 2000s till Ms Le Pen assumed command in 2011. To make the party more mainstream, she adopted a softer approach as compared to her father, which led to a revival of the party's fortunes. In 2017 The National Rally became a credible competitor to the centrist La Republique En March (France on the Move), a party created by Mr Macron in 2016 after he left the Socialist Party.

The National Rally has a history of being extremely nationalistic, xenophobic and even anti-semitic. After the Paris terror attack in 2015, the party exploited the incident and capitalised on the growing anti-Islamic sentiment in the country. Neo-fascist movements are known for their extreme nationalism, and they blame their country's issues on immigrants (mainly non-European immigrants). It is on Le Pen's agenda to control what she claims to be uncontrolled immigration, and she plans to make it more difficult for immigrants to get residence and aid in France.

On top of this, she also wants to end family reunification, which means that immigrants will no longer be able to take up residence if their family members are residents. She wants to abolish birthright citizenship and make it more difficult for immigrants to get the same social security as the French citizens. Although she claims she wants to conserve total freedom of religion, eradicating Islamic ideology is also part of her agenda. She strongly supports banning the hijab from all public areas.

The National Rally is Eurosceptic and advocates exiting the EU, which would raise concerns in Brussels. Le Pen has reportedly close ties with the Russians, although she joined the condemnation of Mr Putin for his Ukrainian invasion. All the same, as part of her declared policy projections, she would like the French military to pull out of the integrated NATO command setup.

In 2017 the gap between Le Pen and Macron in the first round was only 2.71 per cent; this time, the gap is over 4 per cent. However, unlike last time, polling and market research companies do not believe that Macron will win with a large margin the way he did last time. Ifop predicts that the race will end 51 per cent to 49 per cent in favour of Macron.

The third-place candidate was Jean-Luc Melenchon of the La France insoumise, a long term leftist who won 22 per cent of the vote in the first round. Macron supporters fear that with him out of the race, the far left may not vote for Macron in the second round as there is a great deal of economic resentment in the country right now. Le Pen is leveraging nationalism and anti-incumbency sentiments to win over the left-wing voters who traditionally come from the working classes that have been the worst impacted by rising inflation.

Focusing largely on rural communities, Ms Le Pen seems to have resonated well with the farming communities, who too, are suffering from the rising cost of living and negative fallout of globalisation. She has proposed a wide range of tax cuts which has resonated well with the younger generation.

Assessment

- In the past, voters from the centre and the left combined forces to keep the left out of power. This time around, while the leaders are propounding a similar strategy, it is to be seen if the voters are going to translate it into votes. The common people's frustration with economic issues and rising prices are leading to an anti-elite sentiment that President Marcos will have to overcome. The left voters may just give the second round a pass, thus taking away valuable votes from President Macron and reducing the margin of his victory at best and at worst, handing the crown to the right wing.

- In the current surcharged atmosphere of Europe, with rising xenophobia both against the immigrants from Asia and Africa and the slav people in general, the emergence of a right-wing government in Paris could have dire consequences for political stability in Europe.

Comments