Reconciling Fragmented Laws

June 2, 2021 | Expert Insights

In public international law, the right of a state to regulate taxes is undisputed. What is contested, however, is the manner in which it seeks to do so. In the Cairn and Vodafone cases, for instance, the matter under scrutiny was the way in which the Indian government implemented amendments to section 9 of the Income Tax Act. According to the arbitration tribunals in each of the two cases, the enforcement of a capital gains tax with retrospective effect had contravened the guarantee of ‘Fair and Equitable Treatment’ (FET), as enshrined in India’s Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs) with the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. Implicit in this issue are larger questions about the relationship between domestic law, taxation treaties and international investment agreements. The underlying complexities of these applicable regimes and their mutual interaction pose a dilemma for host states and foreign investors.

EVOLVING TREATY REGIMES

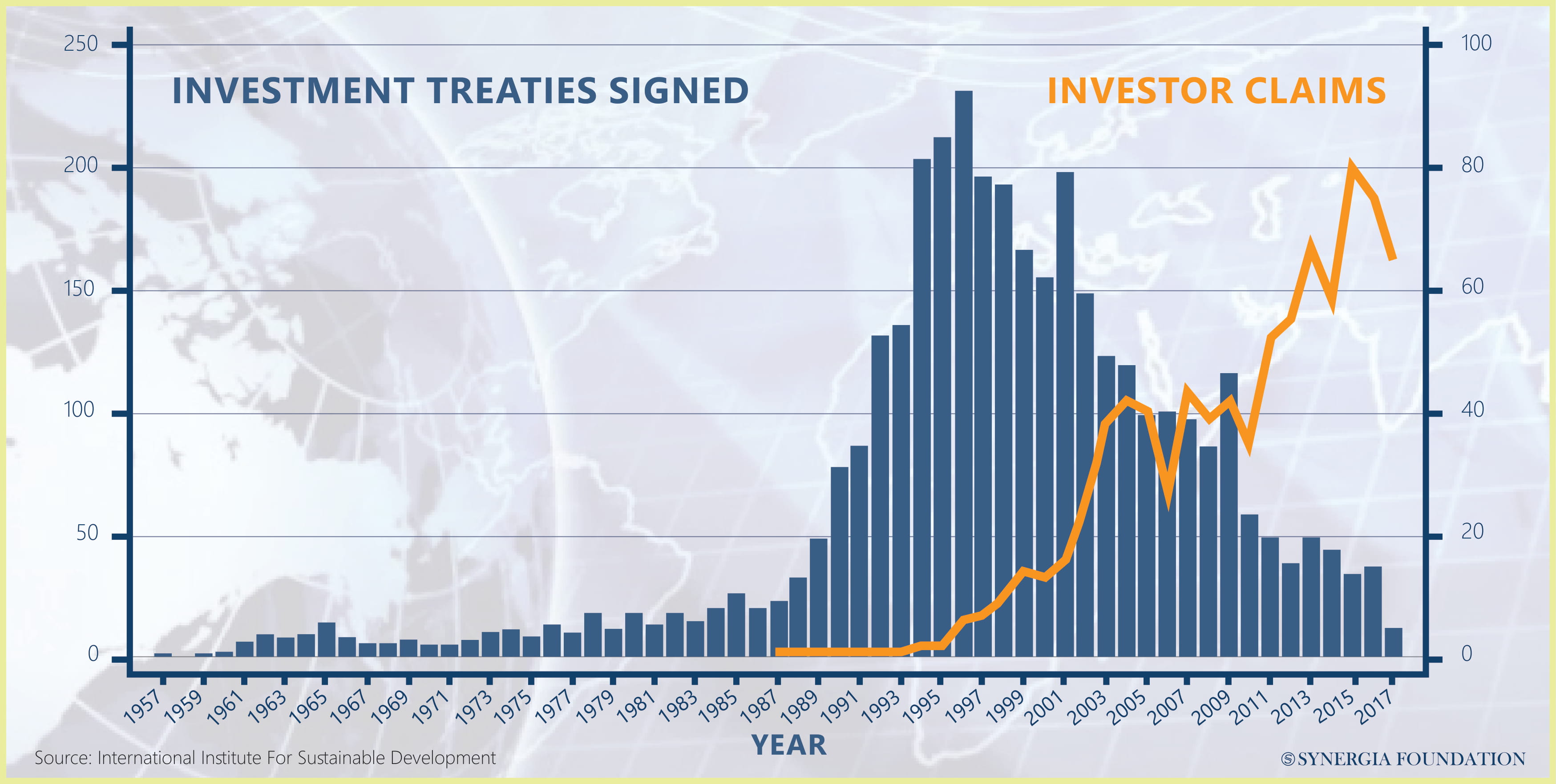

As far as international investment agreements are concerned, there are discernible differences between old generation and new generation treaties. Depending on where one sits in time, the approach to taxation measures may be distinct under these regimes. For example, old generation treaties do not generally exclude tax disputes from their ambit. They also rarely address the interaction between double taxation treaties (DTT) and investment treaties in the event of a discrepancy between the two. Finally, the relevance of any prerequisite criteria for accessing the DTT or an investment treaty in local administrative courts and authorities remains unclear. Meanwhile, some of the newer investment pacts have a tendency to overregulate. They not only specify the relationship between tax treaties and investment treaties but also have explicit carve-outs that elucidate the taxation measures covered within their scope. For instance, the Canadian model BIT has a long provision on taxation measures as well as an obligation to approach local tax authorities for a certain period of time. With the exception of these latest agreements, however, most investment treaties have failed to define ‘taxation measures’. It is unclear whether they relate to the actual imposition of taxes or the interpretation of laws concerning taxes. Attaining definitional clarity on this front is the first step towards fixing the jurisdictional limits of an investment tribunal.

ARBITRABILITY OF TAXES

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) have made significant contributions to the debate on the arbitrability of tax matters. Following several studies and reports published by them, the OECD Model Tax Convention has recommended arbitration as the preferred mechanism for dispute resolution. With respect to investment regimes, the arbitrability of tax disputes is also predicated on the specific carve-outs within the treaty. The definition of ‘investments’ and ‘investors’ are equally critical. In the specific cases of Vodafone and Cairn, for example, the arbitrability of retrospective tax law will depend on the portfolio of shares covered within the definition of investment. In other words, the language of the instrument will be key in determining the types of disputes that are arbitrable in the investment tribunal.

CONDUCT OF STATES

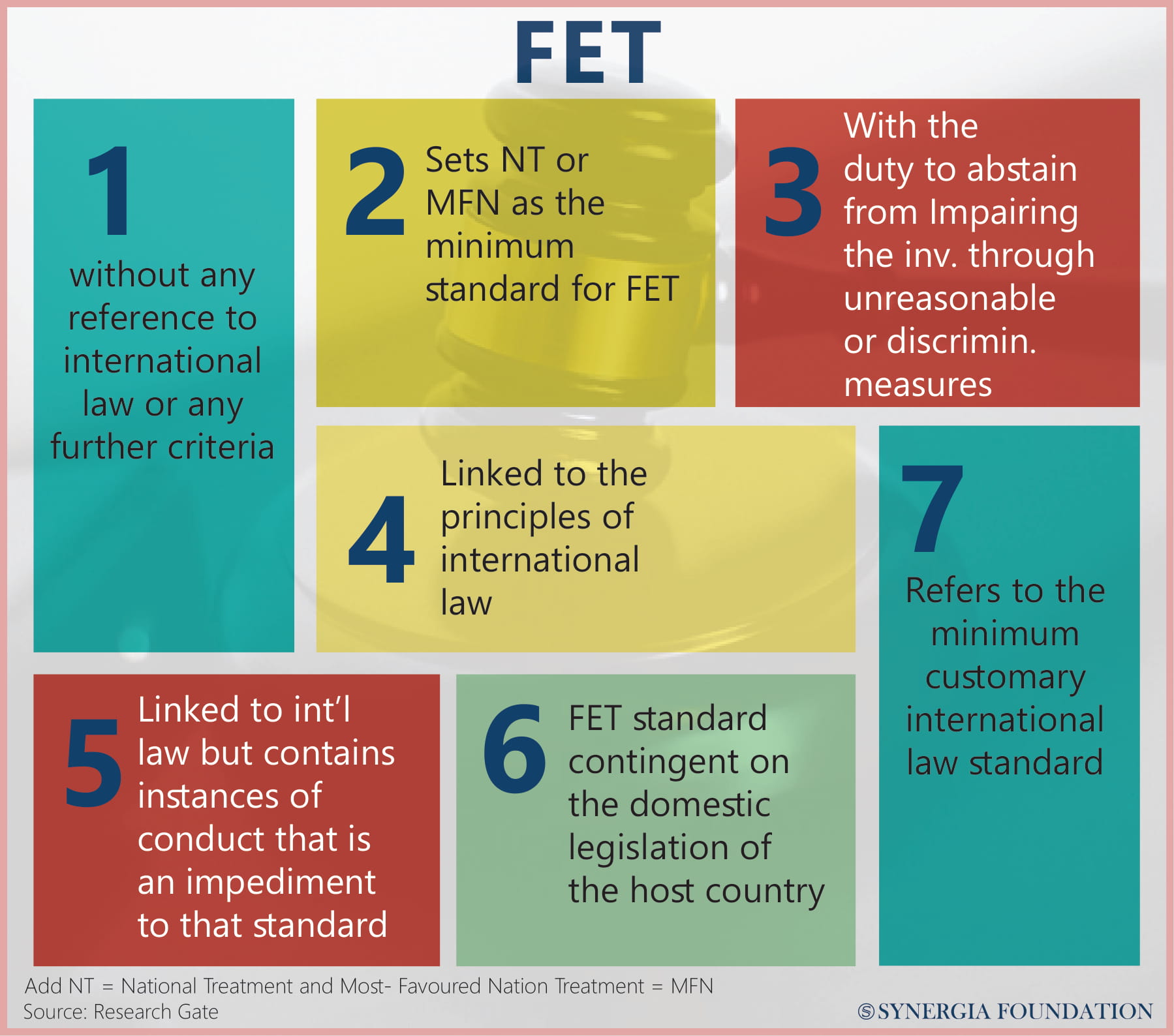

In tax-related investment disputes, it is important to situate the investor within different frameworks of state behaviour. In this regard, there are two kinds of cases that need to be distinguished. The first type relates to cases where existing tax laws are imposed by administrative authorities without any modification. Yukos Shareholders v. Russia is a prominent example. The second type includes cases where retrospective taxes are levied, with implications for principles like stabilisation, legitimate expectations, and transparency. The Cairn and Vodafone disputes fall within this category. The FET standard is critical in assessing the conduct of states. It probes whether the implementation of a tax measure is unreasonable, arbitrary, abusive, discriminatory or a violation of due process. Although this principle is constantly evolving, it primarily interrogates whether the legitimate expectations of an investor have been met by the host state. Other substantive standards of treatment like the expropriation principle or ‘most favoured nation’ status can also come into play, as has been seen in numerous cases pertaining to the non-payment of Value-Added Tax (VAT) refunds, withholding of tax etc. Ultimately, therefore, the manner in which the state imposes tax obligations on its investors will be the object of inquiry in investment arbitrations.

Dr Crina Baltag, is a Senior Lecturer in International Arbitration at Stockholm University and qualified attorney-at-law since 2004. This article is based on her views shared at the 102nd Synergia Forum on ‘Retrospective Tax Law and India’s Global Road Ahead’.

Comments