Pushback on Novartis therapy for muscular atrophy

November 24, 2018 | Expert Insights

Just weeks after Novartis floated the idea that $4-5 million was fair value for its new gene therapy against spinal muscular atrophy, a deadly neuromuscular disease, a major pushback has come from the benefits manager which helps US employers manage workers prescription cost.

Background

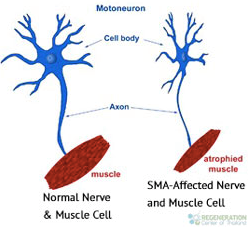

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a severe neuromuscular disease caused by a genetic defect in the SMN1 gene, leading to the loss of motor neurons and resulting in progressive muscle weakness and paralysis. SMA affects one in 10,000 live births; forty per cent of patients have the severest form and historically die within months. Children with less severe SMA can live to adulthood, although with profound physical disabilities. Though cognitively normal, many cannot feed themselves and require 24-hour care, wheelchairs and machines to help them breathe and cough.

AVXS-101 is a proprietary gene therapy currently in development for the treatment of all types of spinal muscular atrophy. It delivers a functional copy of the SMN1 gene to motor neuron cells in SMA patients. The therapy was developed by AveXis.

Swiss drugmaker Novartis, which is shifting into rare diseases, bought AveXis for $8.7 billion in 2018.

Analysis

Swiss drugmaker Novartis, which is shifting into rare diseases, late in October announced that its new gene therapy for the deadly disease spinal muscular atrophy could be cost-effective to healthcare systems at $4 million to $5 million per patient.

Just weeks after Novartis floated the idea that $4-5 million was fair value for its new gene therapy against a deadly neuromuscular disease, a major pharmacy benefits manager Express Scripts, which helps U.S. employers manage workers’ prescription costs, is pushing back.

Its chief medical officer, Steve Miller said he “loves the science” behind Novartis’s therapy, a potential cure for newborns who are diagnosed early. However, he contends with its high cost. “You just can’t keep pushing these price points up,” Miller said. “I just don’t think we can allow it.”

As Novartis prepares to launch AVXS-101, it also hopes for endorsement of its pricing strategy from the non-profit Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER), which is currently reviewing the cost-effectiveness of SMA therapies. The Boston-based non-profit, established in 2006, carries out cost-benefit analyses on drugs independent of “Big Pharma”, insurers and government. Unlike European price regulators, ICER cannot dictate costs, but it has steadily gained influence in the U.S. pricing debate, as companies like Express Scripts and CVS Caremark and governments rely on its analyses. ICER reviewed 11 treatments in 2018.

Seven times, it concluded drugs’ prices aligned with their benefits, like when it said Roche’s $482,000 haemophilia medicine Hemlibra could save the U.S. system up to $1.9 million for the hardest-to-treat patients.

On four occasions, ICER concluded that drugmakers were asking too much, giving payers ammunition to bargain them down.

For instance, the New York Department of Health said that ICER’s finding that a $270,000-per-year cystic fibrosis drug from Vertex Pharmaceuticals represented “low long-term value” helped underpin the state’s demand for a steep discount.

Novartis and Biogen, as well as Switzerland’s Roche, which also has an SMA drug in development, are all lobbying ICER to broaden what it considers a meaningful benefit, potentially helping their therapies fare well in the group’s review.

For its SMA review, ICER aims to quantify factors like quality of life, direct medical costs and how patient and caregiver productivity losses may burden society.

Though newborns may stand to benefit the most from AVXS-101, depending on the durability of its effect, the therapy is also being tested in older SMA patients with more advanced disease in hopes it will improve their symptoms, too.

Counterpoint

But the company has begun its campaign to convince insurance groups and governments to cover AVXS-101, contending the one-and-done infusion will save society money over the long haul, even with a cost near the highest ever for a one-time therapy.

There’s now only one approved drug for SMA, Biogen’s two-year-old Spinraza, and it is listed at $750,000 for the first year and $350,000 thereafter. Spinraza is not a cure and must be taken indefinitely.

“When we look at 10-year costs, you see somewhere between $2.5 million to $5 million being spent by societies to care for these types of patients,” Dave Lennon, AveXis’s president, said.

“Four million dollars is a significant amount of money, but we believe this is a cost-effective point.”

Assessment

Our assessment is that pushing prices of gene therapy as high as $4-5 million per patient might not be sustainable over time; in our opinion, such high costs will make it harder for those suffering from rare diseases to access insurance, as insurers will balk at making payments of several million. However, we believe that the benefits such therapies confer are indisputable.

Comments