PAK ECONOMY INCREASING DISTRESS?

July 30, 2022 | Expert Insights

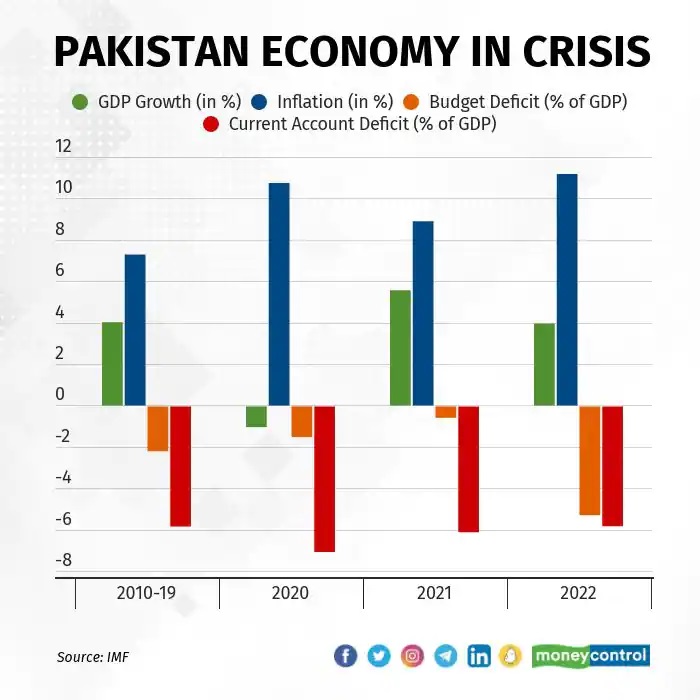

While all eyes are focused on Colombo, another South Asian nation, and a nuclear power to boot, is steadily headed in the same direction.

As per figures of its central bank, the Pakistani rupee, like its Indian counterpart, has been on a steady downslide losing 0.68 per cent last week, bringing the depreciation to nearly 21 per cent for the current year. Only two currencies have performed worse -the Sri Lankan rupee and the Ukrainian hryvnia.

Background

The 1980s were the best years that the Pakistani economy enjoyed despite a savage war on its western borders in Afghanistan. Under the strong control of Gen Zia ul Haq, the military dictator who was responsible for hanging Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the nation was adequately supplied by staples from domestic agriculture and industry and industrial hubs in the Punjab and Sind flourished with liberal government policies. With an average GDP growth rate of 6.5 per cent in the 1980s, Pakistanis felt they were far better off than their towering neighbour and arch enemy India. In fact, Pakistani media was full of refrains about the average Pakistani being much better fed than the average Indian! Foreign remittances from Pakistanis in the gulf nations were very healthy at US $ 3 billion per annum, adding more than 10 per cent to its GDP.

More importantly, for the entire decade, as the U.S. and its Gulf allies baited and bled the Russian bear in the wastelands of Afghanistan, Pakistan was flush with secret funds amounting to billions meant for the Mujahideen but difficult to audit. This was in addition to substantial economic and military aid by the U.S. to its closest Asian ally. The numbers are staggering; between 1980 and 1990, American economic aid amounted to over $3.1 billion in addition to $2.9 billion in military aid. But these happy days were not to extend into the 1990s as U.S.- Pakistan relationship began to unravel and reached a near-dead end with 9/11 and its subsequent consequences. In the 1990s, the Human Development Index of the United Nations Development Program placed Pakistan in one of its lowest development categories, with poverty rates doubling from 18 to 34 per cent.

The current financial situation in Pakistan has its origin in the early 2000s when another military dictator, Gen Pervez Musharraf, crowned himself the 'CEO' and ruled from 2001 to 2008. Although Musharraf tried to cajole the west into giving generously, both for the Pakistani military and its economic survival, claiming its status as a 'frontline state against terror.' But a chastened American administration was far more discriminate this time around with its economic aid, making it conditional on Pakistan's behaviour. Pakistan would never again qualify for unstinted western economic aid and had to turn in desperation to China and the Gulf nations. Unstable political situation scared investors away, and Pakistan found it difficult to even meet its debt obligations. This situation has continued to date, through the tenure of successive prime ministers till the current incumbent Mian Muhammad Shahbaz Sharif.

Remittances and investments have declined by millions, and Pakistan has to constantly struggle to borrow foreign currency from China, Saudi Arabia and IMF every six months to cover its imports and pay its debt dues.

Analysis

The country is facing record inflation of over 21 per cent, and the central bank may spike the key policy rate by 125 basic points. In an economy that is still run like a feudal holding, the economic control rests with a few, who are more interested in their personal fortune than the national wellbeing. Political unrest, terrorism and speculative activity in all spheres of its financial dealing do not promote confidence in external and domestic investors. Wealthy Pakistanis would prefer sending their earnings abroad to safe havens or unproductively spending them on educating their wards in expensive colleges abroad than investing in domestic enterprises.

The hopes infused in the masses by Imran Khan about changing Pakistan's economic future once and for all by providing a corruption-free administration turned out to be as much of a chimaera as his earlier corrupt predecessors. Very early in his tenure, it was amply clear to all but his most ardent supporters that Mr Khan was way out of his depth in dealing with the huge economic pitfalls that his nation was faced with. Within two years, he was out of the office.

While Pakistan differs from Sri Lanka in that its rulers did not try to implement Utopian tax reforms to please their doting electorate, the economic profligacy has not been any less. The military, with its unbridled status as a state within a state and referred to as the ‘deep state', sucks in a significant amount of scarce revenues. Trying to play a strategic role in the region far beyond its true capacity, the Pakistani state has been fomenting trouble in its neighbouring countries -India, Afghanistan and even Iran- which does not come cheap. Furthermore, such adventures have a tendency to blowback, a phenomenon now evident in almost entire Pakistan.

More importantly, it is refusing to open to external examiners the terms and conditions of its closely guarded China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) since 2015 with China, another commonality with Sri Lanka. Without laying bare all the layers of these deals, no international or multilateral organisation is going to risk its dollars on Pakistan. Gwadar is akin to Hambantota, which has tremendous strategic potential as a naval base, but its economic potential (akin to Singapore and Hong Kong, or even Karachi or Mumbai) is linked to an industrially rich hinterland which it can serve. Till the entire CPEC develops as a single economic entity, with linkages in China, Iran and perhaps even Afghanistan, it will not generate the kind of revenue to justify the high rate of sovereign guaranteed interest that cash-starved Pakistan would be paying to its 'forever friend' in Beijing.

Assessment

- Pakistan seems to be on the same sinking boat as Sri Lanka, with depleting foreign reserves and the inability to get investors or loaners. There is a limit to what funding China and Saudi Arabia can do when they too are under economic stress. It is high time Pakistan swallowed the bitter pill of challenging economic reforms before it is too late.

- Pakistan’s obsession as a doyen of ‘asymmetric warfare ‘ in the region has proved costly and earned it a spot on the grey list of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). This honour is the fastest means to scare away foreign investment as no entity, public or private, would, in its right senses, invest in a nation which could potentially be in the same league as North Korea. Since its 'Deep State' runs this part of its foreign policy, it would be difficult for the nation to give up on it as it would take away the raison d’etre for the vast funds provided to it.

Comments