The Nuclear Calculus

April 12, 2022 | Expert Insights

Long comforted by the benign protection of NATO under the domineering leadership of the U.S., the European concept of regional defence has been thrown into disarray by the Russian ‘special military operation’ in Ukraine. A blitzkrieg spearheaded by armoured columns across internationally recognised sovereign borders, reminiscent of Hitler's European campaign of 1939-40, was an event least considered possible by any European state, big or small. Naturally, it has given rise to a climate of fear, distrust, and an all-pervading call for self-preservation at the cost of the larger good.

Background

When it imploded in 1991, the USSR was the leading nuclear power. As per the Arms Control Association, over 35,000 nuclear weapons were deployed over thousands of sites across Eurasia, spanning eleven time zones. A sizeable chunk of its strategic assets was deployed in Ukraine, making the latter the third-largest possessor of nuclear weapons, only behind the U.S. and the newly minted Russian Federation. Ukraine also possessed the facilities and the expertise to design and produce newer versions of nuclear weapons.

A fledgling nation-state, Ukraine lacked all the essential attributes of nuclear power. At this juncture, the greatest concern of the West was to avoid the creation of more nuclear powers. This led to the Budapest Memorandum, wherein Kyiv agreed to give up its nuclear arms in return for security assurances from Moscow, Washington, and London. So, while the rich and powerful continued to retain their nuclear arsenal, Ukraine was disarmed overnight, with promised security guarantees that ring hollow today.

Analysis

President Putin’s ‘special military operation' in Ukraine has placed the very idea of 'security', 'sovereignty' and 'territorial integrity of the larger non-nuclear world in a perilous conundrum. Ukraine, when it became the only country willingly forsaking nuclear weapons and know-how, was assured several safeguards under the Budapest Agreement. After prolonged and complicated discussions attended by the then Russian president Boris Yeltsin, Ukrainian President Leonid Kuchma, US president Bill Clinton, and British prime minister John Major, it was agreed by all signatories to “refrain from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of Ukraine”, with none of their weapons being used against Kyiv, except in self-defence or under the UN Charter. It also forbade them from using economic coercion against Ukraine.

During the negotiations, Ukraine had demanded legally binding guarantees, especially from the U.S., if its sovereignty was violated. The U.S. was unwilling to go that far, so a much watered down version was finally agreed upon. The signatories had agreed to seek immediate action from the UNSC, in the event of any external aggression against Ukraine. Later, France and China also extended similar assurances but refrained from signing the Budapest Memorandum. As the events unfolded last month, none of these guarantees could prevent the death and destruction that one of the signatories, Russia, wreaked on Ukraine.

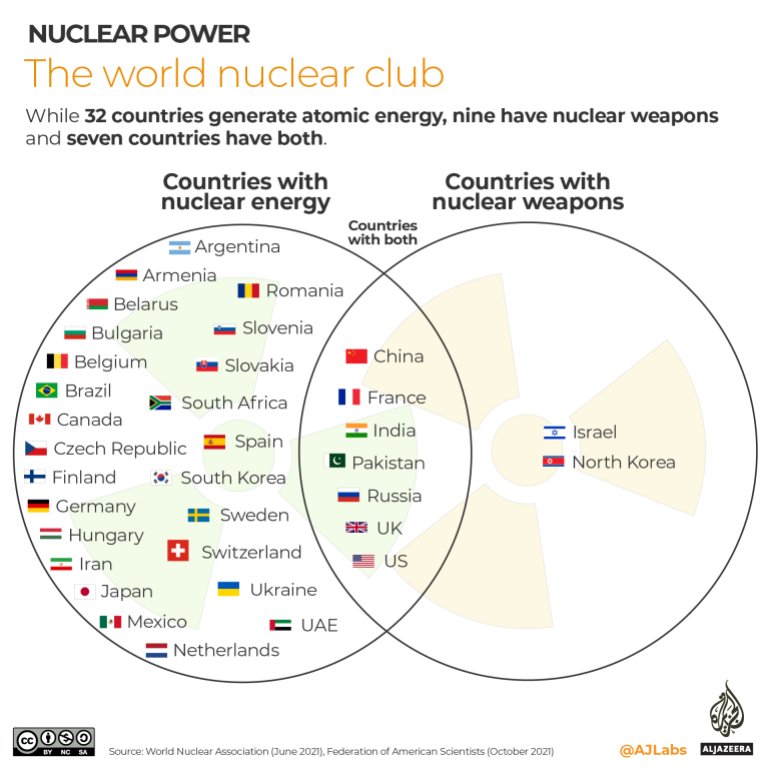

Concurrently, efforts are on to revive the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), better known as the Iran nuclear deal between Tehran and the P5+1 together with the E.U. Like with the Budapest Agreement, the JCPOA also endeavours to prevent Iran from joining the nuclear club. It would be interesting to see how Iran looks at the apparent failure of the Budapest Accord when it sits on the negotiating table to surrender its own nuclear programme to international control. Meanwhile, Moscow has thrown a spanner into the works by demanding the removal of sanctions on its trade with Iran as a precondition to furthering the talks.

Relations between Iran and Russia are complicated. While they seem to support one another, their own national interests always take precedence. For instance, in the past, instead of supporting Iran’s nuclear ambitions, Russia had chosen to support the sanctions against it. This was because banning Iranian exports would enable a larger market space for Russian oil. Similarly, in Syria, there is a rift between the forces supported by both nations for their respective political benefits.

Tehran seems unsure about whose side it is on. Initially, it had put the entire blame of the invasion on Washington's empty promises to Ukraine. However, upon a closer look, both Washington and Tehran stand to benefit from a swift signing of the nuclear deal. The Russian invasion has caused oil prices to skyrocket. If the sanctions are lifted, nearly 80 million barrels of oil stocked in Iran will find their way to the market, meeting Tehran's ambitions of economic revival and Washington's objective of bringing the prices down. With the current sanctions on Moscow in place, cheap Iranian oil will find a larger market, especially in the West, where Russian oil had made in-roads before.

The current Ukraine crisis, therefore, has a two-pronged impact on the Iranian nuclear deal – Moscow’s demand threatens to delay the conclusion of the accord and its arbitrary invasion of Kyiv, in violation of the Budapest treaty, negatively impacts the reputation of other nuclear powers in ensuring peace and global security. Tehran had been keen on closing the deal to revive its economy, but the current war may prompt a rethink on its part.

Assessment

- Given the current economic situation, Iranian oil’s return to the market is likely to benefit all stakeholders except Russia. This creates a dilemma for Iran as it reviews its stand in the Ukrainian war and its relationship with Moscow. From a pure security point of view, giving up on nuclear arms may be perceived as a myopic move by the strong hard-line lobby in Iran, as the war in Ukraine has upset conventional security calculations and long-held threat perceptions. However, Iran finds its anti-West fixation at loggerheads with its economic prosperity.

- From Moscow's viewpoint, Iran's abstentions from voting against Russia is a positive sign, keeping alive hopes of future trade and investment with Tehran when most of the world appears poised to isolate it.

Comments