Navigating the Terrain of Public Policy

June 2, 2021 | Expert Insights

The Cairn arbitration case has once again thrown the limelight on issues surrounding India’s tax laws, with a primary focus on the ‘retrospective’ aspect of taxation. Ensuring the State’s right to rightfully tax private companies while safeguarding the investors’ rights is by itself a balancing act. Currently, when one thinks of India and investment arbitration, there appears to be a sense of cynicism, which needs to be dispelled.

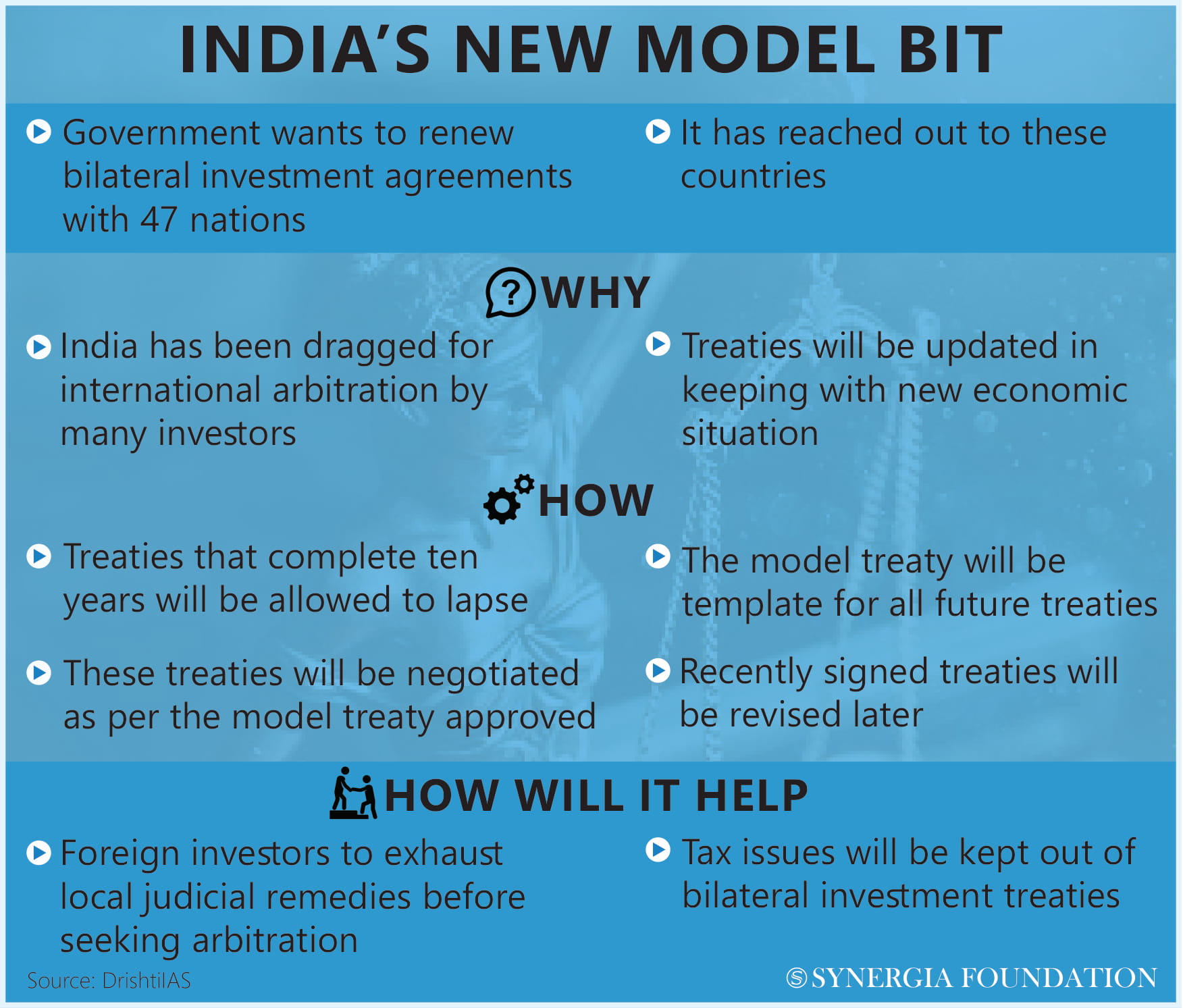

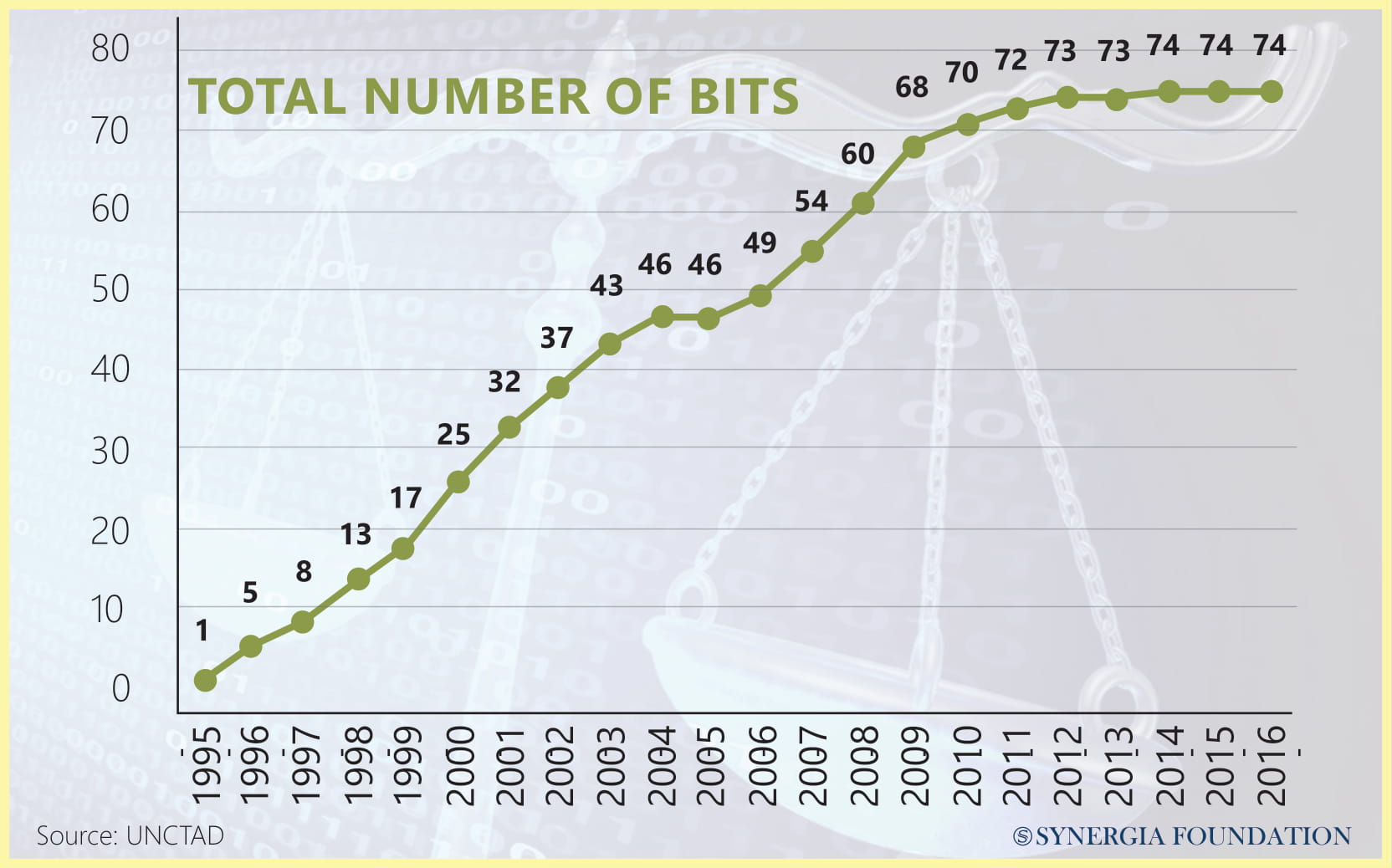

India certainly suffers from various arbitration concerns. Having been under media scrutiny due to the Vodafone and Cairn disputes, the problem that seeks urgent attention is the matter of retrospective tax. With regard to the Cairn issue, actions are being currently taken to seize Indian assets on foreign soil to recover the amount awarded by the international arbitration tribunal. There have also been other cases, such as the 2G spectrum dispute, with its various corruption charges, that have led India to respond in a threefold manner. Firstly, India has terminated its Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs). Secondly, it has proposed a new model BIT, which specifically excludes taxation measures. Thirdly, India has defended its actions under the wide ambit of public policy. Since public policy brings within its fold the question of arbitrating disputes, India has taken the position that tax disputes are non-arbitrable.

PUBLIC POLICY EXCEPTION

There is a legitimate expectation on the part of investors that laws would not be changed to their detriment. While the way forward in the new Indian model BIT is to exclude taxation measures, the question remains whether this can be retrospectively done under the garb of national interests, security concerns and the public policy of a State. This, in turn, begs the question – ‘what is public policy’? Most developing countries, when faced with an arbitration claim, tend to mix up domestic policy with public policy qua domestic policy, and public policy with respect to international law. All attempts to generate an international or a transnational public policy till date, have been unsuccessful. Hence, the line between public policy and political interests is often blurred. States ought to take into consideration the real intent behind the public policy exception in international law, and more specifically, in international arbitration. In arbitration, the public policy exception extends to violations of the most fundamental notions of justice, morality and ethics or such violations that strike at the root of the sovereignty of a country. Therefore, the public policy defence extends to mandatory law or lois de police and not to actions taken under the garb of public policy.

WHAT SAYS INDIA?

Recently, the Supreme Court, in the case of Vidya Drolia v. Durga Trading, for the first time, clearly laid out what it considers as public policy. This is relevant for two reasons. Firstly, it helps decide whether the issue is arbitrable or not. Secondly, it clarifies whether you can resist enforcement on the grounds of public policy. On the one hand, that which is arbitrable under domestic law automatically becomes arbitrable under international law. However, the reverse scenario is unclear, muddying the position on public policy exceptions. For instance, when something is non-arbitrable under Indian domestic law, but is arbitrable in the US such as competition law, where does one draw the line?

The question that needs to be addressed at the policy level is whether there exists any solution to prevent States from claiming public policy as an excuse to justify their taxation measures. In the Devas Multimedia case, India cancelled telecom licenses citing security concerns. While one tribunal agreed with this interpretation and reduced India’s liability, under the German BIT, it was held that there were no security concerns involved and that this was simply an inequitable treatment being meted out to the investor. Indian policymakers need to decide whether the State is willing to distinguish between domestic public policy and international public policy. In the absence of such clarity and much-required certainty, neither can investors be adequately protected nor can India successfully defend its actions as a sovereign. This distinction will also bolster the confidence of other nations to reciprocate protections for Indian investors. Furthermore, a clear legislative intent that delineated the contours of public policy will make enforcement of arbitral awards easier.

POTENTIAL TRAJECTORIES

If domestic remedies have not been exhausted, can the entire arbitrable process be completely thwarted, given the lingering option of public policy? Should stabilization clauses be reintroduced to prevent actions such as the nullification of Supreme Court judgements? One can also debate if the solution lies in having joint committees between states, before an investor claim is brought for arbitration, as India has sought to do in recent times.

Ajar Rab, is a Partner, Rab & Rab Associates LLP, based out of Dehradun. He is also an International Policy Consultant at Lexidalean, an international policy consulting firm. He has published several articles on international arbitration, and has authored books on real estate law and drafting of commercial contracts. This article is based on his views at the 102nd Synergia Forum on ‘Retrospective Tax Law and India’s Global Road Ahead’.

Comments