Mining the Seabed-boon or Bane?

January 28, 2023 | Expert Insights

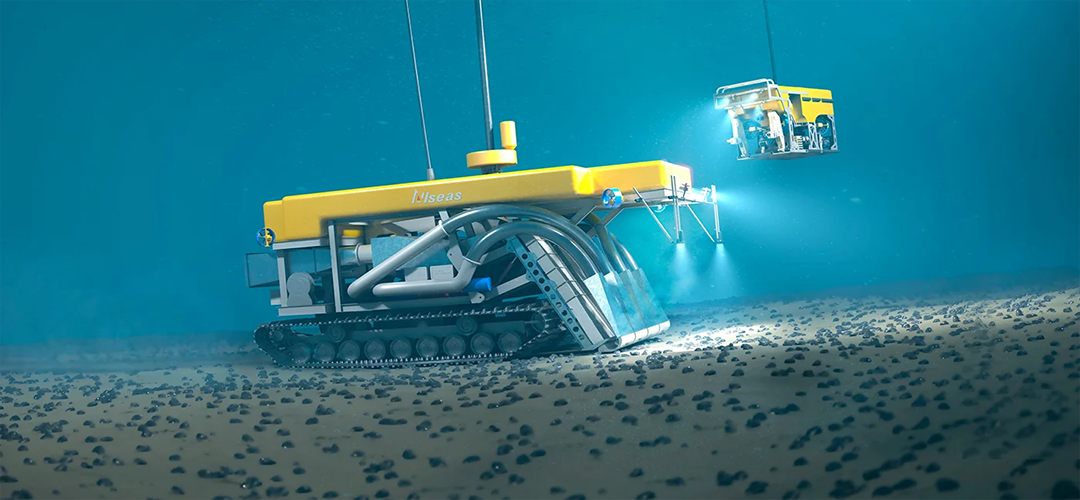

A Canadian private enterprise, The Metals Company, has recently announced its plans to launch the first commercial deep seabed mining operation in the Pacific Ocean after completing an exploratory project in the Pacific region in October 2022.

The International Seabed Authority (ISA) is the lead agency nominated by the UN to regulate exploration for and exploitation of deep seabed minerals in the 'Area', which UNLOS defines as the seabed and subsoil beyond sovereign jurisdiction. In fact, the 'Area' encompasses over 50 per cent of all seabed on Earth!

Although primary seabed mining is already taking place within continental shelf regions at relatively shallow depths, ISA has not officially approved deep-sea mining.

The plans of Metal Company to start provisional deep seabed mining by early 2023 have been met by howls of protests from many countries and rival companies. These objectors urge more research on the procedures, regulatory safeguards and environment impact assessments before commercial seabed mining begins in real earnest.

France and New Zealand stand out for advocating a complete ban on deep sea mining, given the deep economic, political, and environmental challenges it poses.

Background

A 1974 CIA-sponsored expedition called Project Azorian discovered several manganese nodules on the seafloor for the first time. Analysis showed that these nodules are extremely rich in 37 metals, including nickel and cobalt, which are needed for most large batteries and renewable energy equipment. The Clarion-Clipperton Zone, situated between Mexico and Hawaii in the Pacific Ocean, where the expedition took place, has been estimated to harbour over 21 billion metric tons of nodule reserves- enough to produce twice as much nickel and three times more cobalt than all the existing land-based reserves, besides being ten times richer than comparable terrestrial mineral deposits.

The value of this new industry is estimated to grow to US$30 billion annually by 2030 because of its potential to meet surging global demand for cobalt, which is crucial for synthesising lithium-ion batteries.

Despite extensive exploration, only a few countries, such as New Zealand, have established institutional and legal frameworks for the future proliferation of deep seabed mining.

Papua New Guinea (PNG) granted the world's first deep-sea commercial mining license to Nautilus Minerals Ltd, a Canadian company, in 2011. However, three independent reviews of the environmental impact statement found significant policy gaps in the company’s proposal and bypassing of rules to acquire approval. Faced with stiff opposition, the company could not start operations. In fact, in 2019, PNG citizens called for a full ban on deep seabed mining.

However, owing to the increasing pressure from the French, Canadian, U.S., and Chinese deep-sea mining companies, instead of a full lifetime ban on deep sea bed mining, Fiji and Vanuatu proposed a 10-year moratorium to allow comprehensive scientific research on Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) and territorial waters, which was later acceded to by Papua New Guinea.

Analysis

Rising demand for rare earth minerals and metals has led to a resurgence of interest in exploring mineral resources located on the deep seabed, despite the unknown fallout of tampering with the delicate ecosphere of ocean depths.

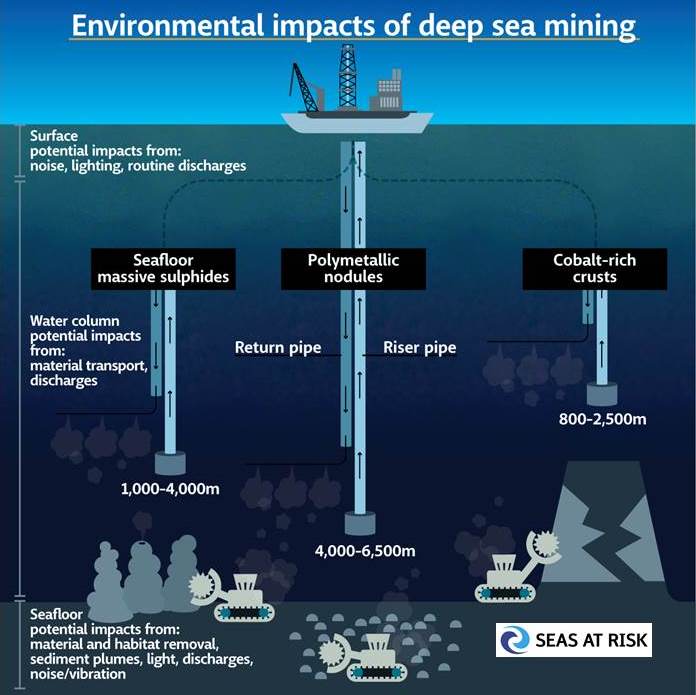

With the demand for renewable energy growing and batteries forming the core of this technology and land-based mineral resources fast depleting, it is only a matter of time before mankind's hunger for minerals will turn the attention of commercial mining towards the last frontier remaining-ocean sea beds. Potential exploiters talk glowingly of massive (polymetallic) sulfides near hydrothermal vents, cobalt-rich crusts (CRCs) around seamounts or fields of manganese (polymetallic) nodules on the surface of abyssal plains which could feed our hungry factories for decades.

The adverse impact of terrestrial mining over the centuries has proved beyond doubt its devastating effect on the health of mining communities and the environment in general. Furthermore, since many rich sources of rare Earth and minerals lie in politically unstable African countries, like the Democratic Republic of Congo, mining has become a tool for geopolitical competition. With many mineral-hungry industrial nations being shut out of the mineral resources of countries like DRC by leading mine owners like China, it is a natural fallout that these countries would seek an alternate and equally lucrative source. By all accounts and estimations, the deep ocean seabeds are rich in these resources, just waiting to be exploited. However, there is no denying that geopolitical competition and conflicts may shift to the ocean seabed when deep sea mining commences!

One school of experts advocate recycling rare Earth and metals to make them last longer and reduce the pressure on fresh mining. However, technology can unlikely make recycling so efficient and cost-effective that the demand for raw materials from mines would fall- at least not when we look at the rate at which consumption is galloping ahead.

Minerals extracted from ocean seabed would indeed augment the global supply of minerals used in clean energy sources such as wind turbines, electric vehicles and photovoltaic cells. They would also reduce the monopoly on these minerals enjoyed by countries like China. However, it will come at a price to the flora and fauna and the delicate ecosphere of the ocean bed and its coastline. What about the survival and well-being of the diverse assemblages of marine species that inhabit ocean depths, some of whom are unknown to our scientists? Environmentalists speak of these species being smothered by plumes of sediments thrown up by high-pressure pumps digging for nodules, endangering and disrupting the natural cycle of all marine inhabitants, an essential part of the life cycle of island communities dotting the region.

The Metals Company has argued in its defence that deep seabed mining has fewer harmful repercussions than terrestrial mining. This may be theoretically true, but given our lack of knowledge and experience of the ecosystem in deep ocean sea beds, this cannot be accepted at face value without establishing concrete environmental baselines for oceanic health. Additionally, given the current nascent stage of the technology used for deep-sea mining, immediate embarking without adequate research might involve uncertain returns.

Assessment

- Deep seabed mining is endorsed mostly for the lack of environmental pollution associated with terrestrial mining. However, this doesn't consider the dangers this activity could present for the Earth's largest pristine ecology — the deep sea- especially since the ISA hasn't framed any environmentally sustainable seabed mining guidelines.

- If managed effectively and sustainably mined with efficient, non-polluting technology, in accordance with international solidarity as enshrined in the UNCLOS, deep sea mining has the potential to help realise the Sustainable Development Goal 14, particularly for geographically disadvantaged and landlocked States, and small island nations which heavily rely on the ocean and its resources for economic development.

Comments