Making Amends, Finally?

April 14, 2021 | Expert Insights

A subject long-simmering and debated in different forms has once again resurfaced, albeit amidst more formal settings. Capitol Hill is preparing for a debate on reparations for slavery to African Americans, as per White House spokesperson Jen Psaki.

Proposed Studies on the subject have the support of President Biden, who will decide on the form and nature of the reparations. Vice President Kamala Harris had spoken favourably about reparations during her campaign, and recent reports indicate that she does not consider monetary reparations as adequate compensation for the centuries-old systemic racism existing in the country.

Reparations have a history and have been imposed on vanquished countries, the last major ones being the First World War. They seek repayment for perceived injustices, and over the years, Native Americans have received land grants and other benefits for being forcibly evicted from their traditional tribal areas during the settling of the American West. Japanese Americans, interned in large numbers during the entire duration of World War II, were able to win over $1.5 billion at around $20,000 per head.

In 1889, soon after the Civil War, the HR 40 Bill was introduced, proposing 40 acres of farmland for each African American emancipated along with an Army surplus mule. The next hearing on the Bill was held in 2017 before Barack Obama was elected as president!

WHAT ARE REPARATIONS?

A typical reparation process goes through three steps- acknowledgement of wrongs imposed, redressal, and closure. Slavery in the U.S. has largely attracted discussion on the first.

Slavery remains a blot on American democracy; over 15 per cent of the inmates dying during transportation from Africa. White farmers with vast cotton fields in the American South, became immensely rich and powerful on the backs of their slaves, who suffered horribly. In 1860, more than $3 billion was the value assigned to the physical bodies of enslaved Black Americans — this was more money than was invested in factories and railroads combined.

Yet, their progeny have not received, to date, reparation in any form; neither has the racial discrimination abated significantly.

The case for reparations is generally about money, but can be made on social and moral grounds as well. On the question of what and who should be included in a reparations package, it could cover those who can trace their heritage to people enslaved, or the whole community in general, considering the ripple effect of systemic repression. One frame of reference could be the U.S. programme, the Marshall Plan, enacted to help ensure Jews received reparations for the Holocaust.

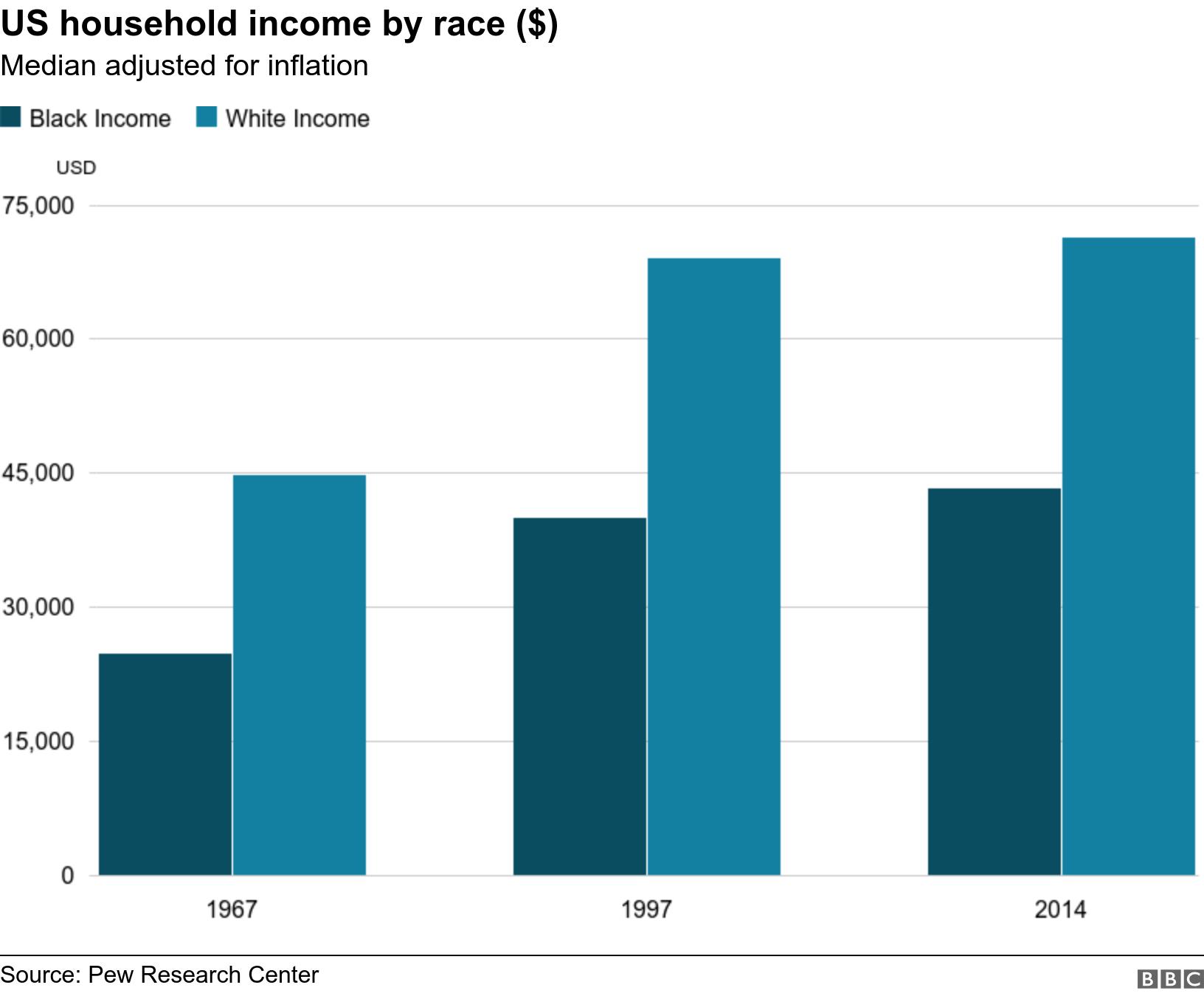

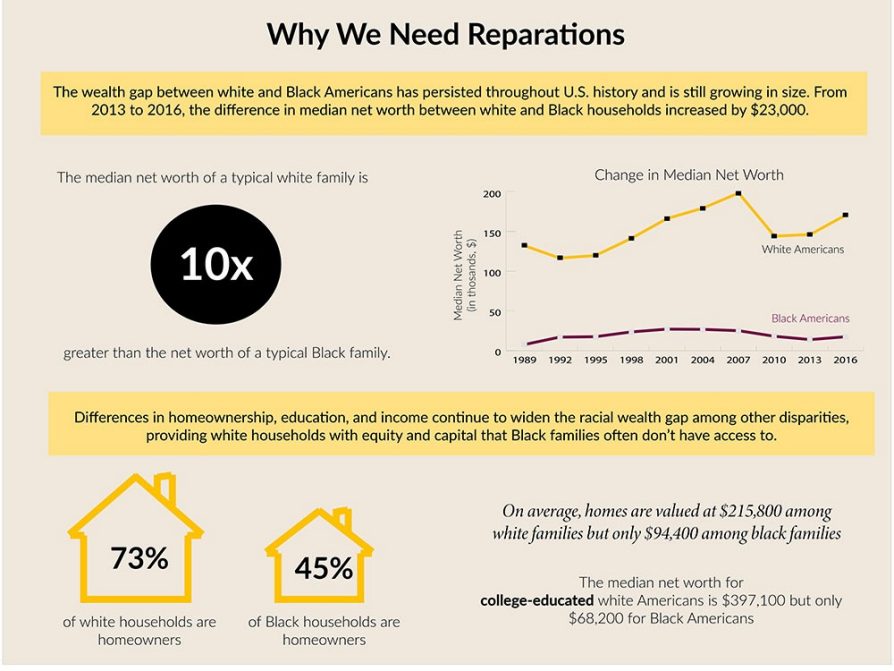

The African American community in the U.S., has never been able to reduce the huge socio-economic gap separating them from their White compatriots. Prominent economists William “Sandy” Darity and Darrick Hamilton pointed out in their 2018 report, What We Get Wrong About Closing the Wealth Gap, that “Blacks cannot close the racial wealth gap by changing their individual behaviour — i.e. by assuming more ‘personal responsibility’ or acquiring the portfolio management insights associated with ‘[financial] literacy’”. To put into perspective how much slavery has set back the average Black family, consider that the average White family has roughly ten times the amount of wealth. According to the Federal Reserve’s numbers in 2016, based on the Survey of Consumer Finances, White families had the highest median family wealth at $1,71,000, compared to Black and Hispanic families, who had $17,600 and $20,700, respectively.

Black Americans themselves have been ambivalent about reparations and did not bring it up as a priority issue in various influential polls, perhaps having given up on it as a lost cause.

However, as the race for 2020 elections gathered pace, Washington Post claimed that at least four Democratic presidential candidates -- Elizabeth Warren, Kamala Harris, Julian Castro and Marianne Williamson – strongly advocated African-American reparations. Then came the George Floyd protests, which spurred the Democrats to include it in their campaign narratives and resulted in infusing fresh life into the issue.

However, despite the rhetoric, on the ground, only the city council of Asheville, in western North Carolina, which is only 12 per cent Black, unanimously passed a resolution approving slavery reparations in August. Yet, this too stopped short of direct payments and rather focused on providing funding for promoting homeownership and business opportunities.

THE DEMOCRATS’ VIEW

In March 2019, Ms. Harris speaking to the National Public Radio, said, “the term reparations, it means different things to different people,” before saying that she sees reparations as the “need to study the effects of generations of discrimination and institutional racism and determine what can be done, in terms of intervention, to correct course”.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) further expanded the scope by asking for the inclusion of the Native Americans in any such move on reparations. She was referring to the proposed American Housing and Economic Mobility Act that would provide financial support to first time home buyers. While this was received positively, the scheme cannot be termed as reparations for slavery.

The Republicans contest the idea of reparations as a matter of principle. This was put across unambiguously by the Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell while he told reporters in June, “I don’t think reparations for something that happened 150 years ago when none of us currently living are responsible is a good idea”, pointing out that the election of a Black president was proof there was no need for such a task. When Buncombe County in North Carolina tried to follow Asheville in approving reparations, the vote was 4-3, with all three Republicans opposing the idea.

Assessment

- While the conversation about reparations starts with money, it goes way past monetary considerations. Black Americans make up 13 per cent of the nation’s population, but their share of the nation’s wealth is only 2.5 per cent. Few programmes propose closing the wealth gap by direct cash payments that would encourage economic growth in the overall community, yet this still doesn’t focus on other facets like, the day-to-day discrimination in job searches, housing, and healthcare.

- Money could be one of the low-hanging fruits that can be focused on, with the others being removal of educational barriers, health disparities, neighbourhood developments, and helping Black businesses, to name a few.

Comments