MAINSTREAMING GENDER IN ROAD TRANSPORT

December 24, 2022 | Expert Insights

The World Bank has compiled a guide for designing women-friendly public transport in Indian cities based on the findings of how women's travel is intrinsically different. Such a report should be a welcome move considering that urban mobility systems are inconvenient, unsafe and unaffordable for women, inhibiting their ability to move out of their homes and participate in economic activities at par with males.

Background

The report is in response to a 2019 World Bank-supported survey of 6,048 respondents in Mumbai, which found that between 2004 to 2019, men shifted to two-wheelers to commute to work, while women used auto-rickshaws or taxis. Naturally, the cost per trip was much higher for women.

Poorly designed public transport systems that do not consider women's safety and specific travel requirements can severely limit women’s access to work, education and life choices. This is particularly concerning in the context of India having one of the lowest female labour force participation rates globally, at 19.23 per cent in 2021-22.

Analysis

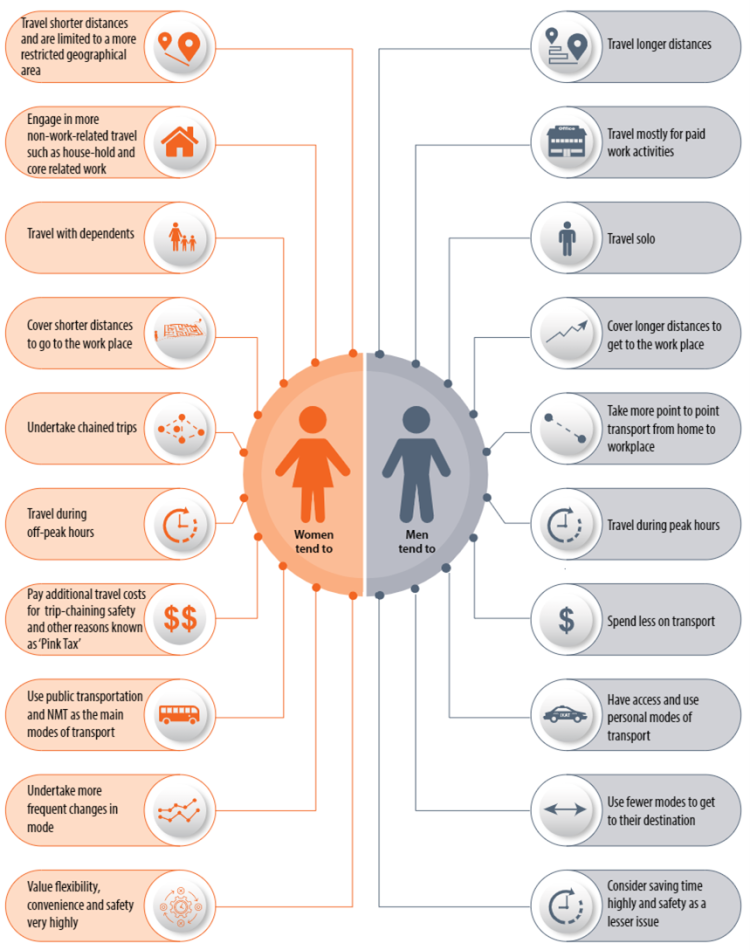

Women, especially those from lower socio-economic groups, are among the biggest public transport users in Indian cities. Their dependence on public transport stems from lower discretionary incomes and unique mobility patterns such as travelling shorter distances, using multiple modes of transport, and travelling with dependents, during “off-peak hours”.

Since the burden of care work (mostly unpaid) lies disproportionately on women, they often need to plan their travel far more meticulously than men, juggling various home and work responsibilities. This means that women have a far greater need for public transport to be punctual, safe and efficient, with longer waiting times and delays having a deleterious effect on them.

As has been proven in communities worldwide, low ridership among women is directly related to the transport infrastructure provided by governments. Several policies and interventions find a place on paper but are rarely implemented and followed up. For example, free bus transport is of little use if buses are few and far too crowded for women to feel comfortable travelling in them, in poor shape, or inaccessible from residential zones.

It has been analysed that the higher cost of travelling women face is also due to the peculiar nature of their daily commute. Unlike men who go from home to office and back as per a fixed route and schedule, women, due to their assorted responsibilities, may have to resort to trip chaining, i.e., during the commute, making several stops (drop children at daycare, buy vegetables, go to the doctor etc.) before heading for the place of work. At times, this may entail being compelled to use more expensive means of transport as public transport may not ply in that area, or the route is unsafe for a woman walking alone.

The lack of affordable and convenient public transport profoundly impacts women's ability to access education and employment opportunities, leading to poorer life outcomes for them. Studies have also shown how distance from home impacts women's choice of colleges and other educational institutions — and by implication, their financial independence.

Moreover, as per the World Bank report, more women tend to walk to work compared to men. Hence, several interventions in public spaces, including adequate street lighting and improved walking and cycling tracks that particularly benefit women who are big users of non-motorised transport, are imperative. Devising lower fare or zero-fare policies can certainly boost greater mobility for women and persons of other genders. More important is creating facilities in the existing transport system, crowded as they may be, to keep women safe, including a strong grievance redressal system that promptly and effectively deals with sexual harassment episodes that women in India consistently suffer. This will go a long way in correcting India’s lop-sided labour force composition, heavily tilted in favour of males, by encouraging women to seek formal employment in workplaces, even far from home.

Ultimately the crux of the World Bank Report on gender-responsive public transport is not to make gender an additional concern for policymakers and developers; instead, it is to integrate a gender lens into everyday planning and development. This will make Indian cities safer and more accessible to women- a principle that needs to be incorporated into India's urban mobility systems.

Assessment

- With safety issues turning women away from using public transport, a vicious cycle is created — unsafe transport leads to fewer women travelling out, which in turn leads to fewer women out in public spaces, which actually makes these spaces even more unsafe.

- Gender-blind planning, infrastructure development and investment leave major gaps that prevent women from fully participating in the nation's economic activities. Considering that women form 48 per cent of the total population of India, it implies that much of this percentage is not employed gainfully in the formal sector, even if their contribution in the informal sector remains very high.

- For a country like India that considers its youth dividend as an enabler towards achieving one of the largest global economies, women stakeholders too must be adequately represented, and greater effort must be made to understand the on-ground situation with a gender lens.

Comments