A ‘look Through’ Provision

June 2, 2021 | Expert Insights

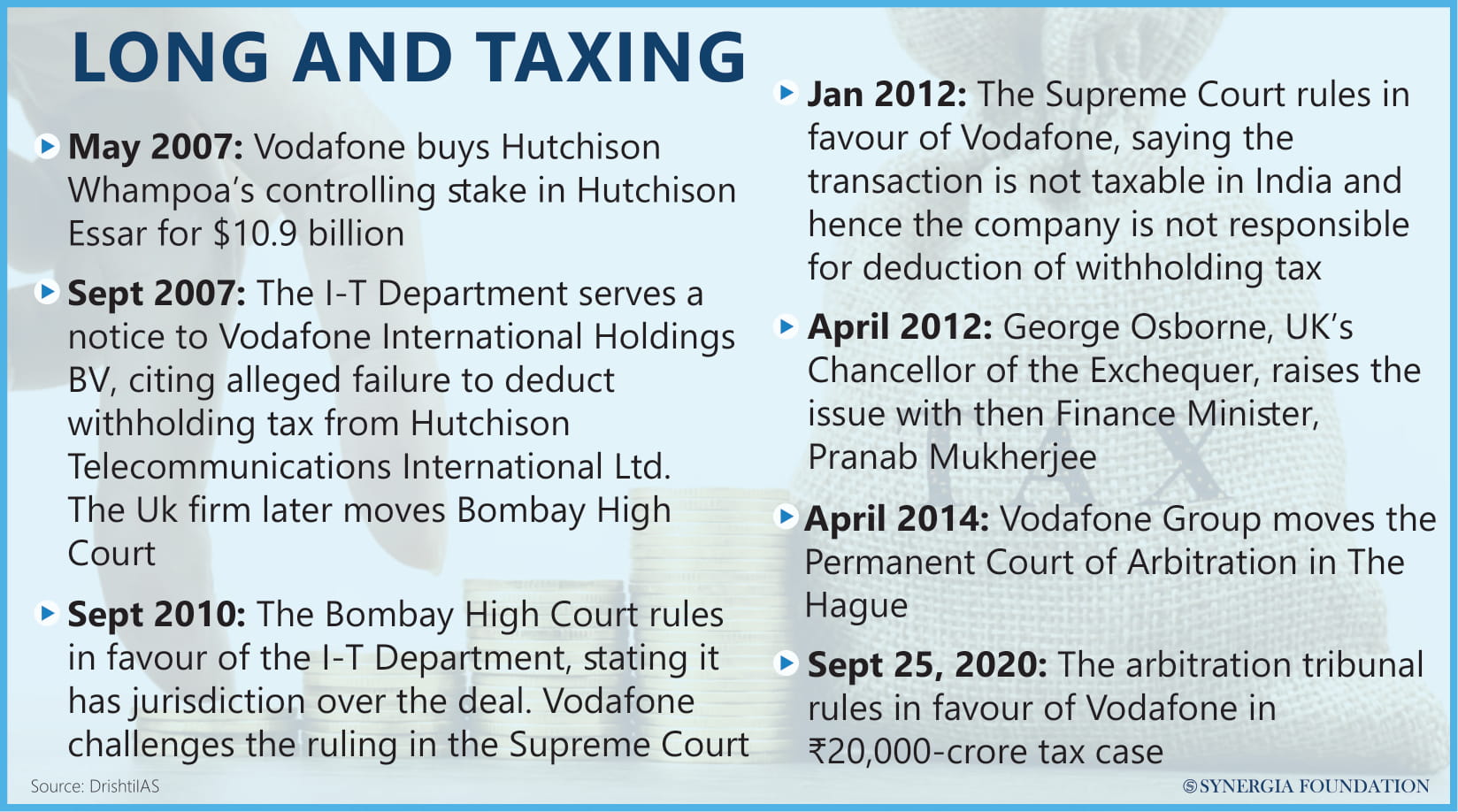

The root of the debate on retrospective tax and international investment law can be traced to the Vodafone case, which was decided by the Indian Supreme Court in 2011. This case pertained to a transaction between two non-resident companies, which was subsequently sought to be taxed by the Indian government. Vodafone had acquired shares in a company in the Cayman Islands, which was essentially a paper enterprise without business operations. On acquiring that upstream company, downstream companies which had their asset base in India were automatically transferred to Vodafone. Against this backdrop, the question that emerged was whether this particular transaction could give rise to capital gains tax in India under section 9 of the Income Tax Act, 1961. After all, its value derived from underlying assets in the country, represented by the Hutchinson company’s operations in the telecom sector.

CONFLICTING POSITIONS

Vodafone argued that the relevant shares were located in a Cayman Islands company, and therefore if any tax had arisen, it was liable to be levied in this British overseas territory. Meanwhile, the

Indian Revenue Department pointed out that the structure in the Cayman Islands had been created for the sole purpose of dodging tax. There was a very fine line between tax avoidance and tax evasion, with the latter being strictly prohibited by the law. Given that capital assets in India had been transferred and payment made to a non-resident entity, Vodafone was required to deduct tax at its source.

Clearly, therefore, there were diverging interpretations about the import of section 9. While Vodafone believed that taxes had to be levied in accordance with the structure of the transaction, the government reasoned that the veil of the corporate structure had to be pierced in order to ascertain the substance of that transaction. In other words, the two sides disagreed whether section 9 was a ‘look at’ stipulation or a ‘look through’ provision.

APEX COURT VERDICT

Ultimately, this case was brought before the Indian Supreme Court, which had to assess various legal doctrines to arrive at a decision. The Westminster principle that entitles every taxpayer to arrange his affairs within the limits of the law was particularly noted during the course of the proceedings. The Ramsay principle was also touched upon,

given that it allows transactions to be taxed if they have pre-arranged artificial steps that serve no commercial purpose other than the saving of tax. Even the McDowell case (CTO v. McDowell and Co. Ltd.), which upholds the right of companies to maintain a tax-efficient system within the framework of the law, was referred to. Eventually, after hearing the case for around 32 days, the Apex Court upheld the interpretation by Vodafone.

EX POST FACTO LAW

Circumventing this judgement, however, an amendment was brought in through the Finance Act by the Indian Parliament, which conferred the Income Tax Authority with the power to retrospectively tax such deals. It is pertinent to note that there are several judgements passed by the Supreme Court that uphold this sovereign right to amend tax laws, including Rai Ramkrishna and Others v. The State of Bihar (1963 AIR 1667) as well as Calcutta Division v. National Tobacco Ltd. (1972 AIR 2563). In the instant case, however, it is vital to understand that the amendment to section 9 was essentially clarificatory in nature. Instead of imposing a new tax, the legislature sought to confirm that the provision always had a ‘look through’ approach built into it.

Arijit Prasad, is a Senior Advocate at the Supreme Court of India, with extensive experience in corporate tax and commercial arbitration. This article is based on his views shared at the 102nd Synergia Forum on ‘Retrospective Tax Law and India’s Global Road Ahead’.

Comments