Kingdom Caught in Crossfire

July 16, 2020 | Expert Insights

Bhutan shares over 470 km of border with Tibet, an autonomous region of China. This border has never been officially demarcated or acknowledged formally by the two countries.

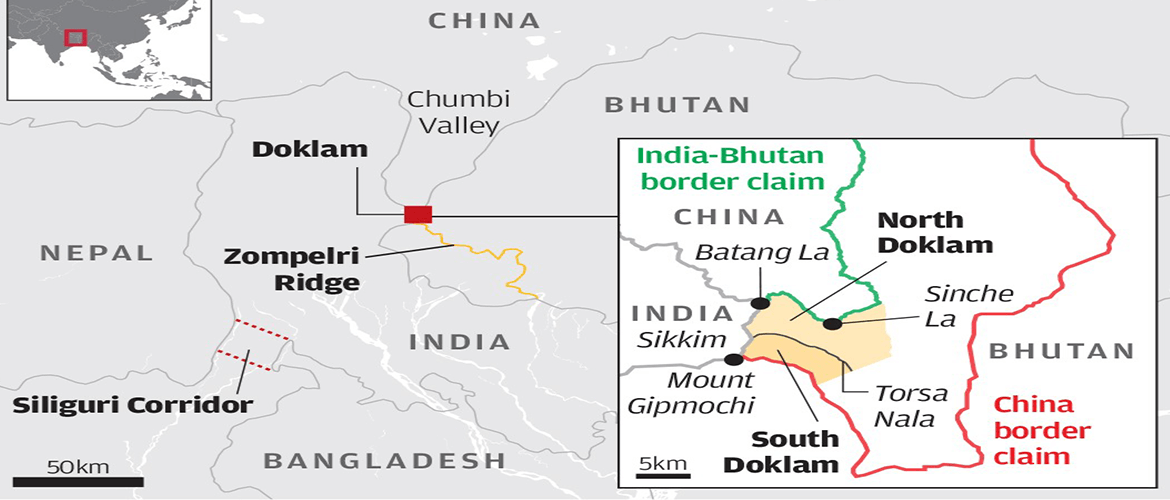

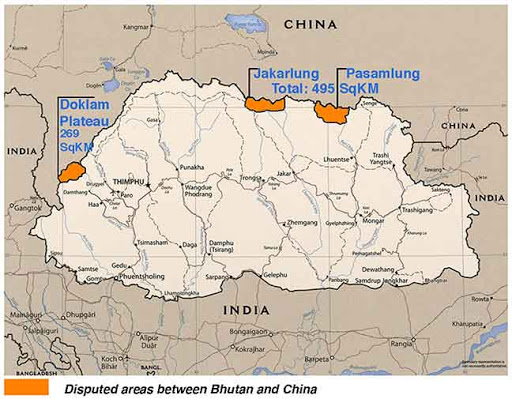

In the 1950s, Mao’s China, emerging from a civil war, was in the process of consolidating its territorial suzerainty. It published maps which clearly infringed upon Bhutanese territory, claiming areas in the northwest (Doklam, Shinchulung, Dramana and Shakhatoe in Samgste, Haa and Paro districts) and central Bhutan (Pasamlung and the Jakarlung valleys in the Wagndue Phograng district). This was followed by frequent ingress by herders and People's Liberation Army (PLA) soldiers. For Bhutan, these lands traditionally and historically were always governed by Thimpu. In 1959, Bhutan was, in a way, embroiled in the fighting in Tibet when it granted entry to over 6,000 Tibetan refugees. This was soon stopped, fearing Chinese reprisals.

During the 1962 war, while Bhutan maintained strict neutrality, it turned a blind eye to Indian troops withdrawing from North East Frontier Agency (NEFA) through Bhutanese territory.

NEGOTIATING WITH THE DRAGON

In the 1980s, the Deng Xiaoping regime was better disposed towards discussing territorial disputes, and the first engagement phase with Bhutan was initiated in 1984. Till then, the Sino-Bhutan boundary issue was viewed through the prism of the wider Sino-Indian border negotiations; now China wanted to engage Bhutan bilaterally, presumably to weaken Indian influence over foreign affairs of its close ally Bhutan.

In 1996, China proffered a resolution package allowing Bhutanese ownership of Pasamlung and Jakarlung valleys in exchange for Doklam, Sinchulung, Dramana, and Shakhatoe. The deal never materialised, because of the sensitivity of the Doklam plateau to India. However, in 1998, both countries signed a Peace and Tranquillity Agreement, which for the first time acknowledged the sovereignty of Bhutan as an independent country. Since then, on several occasions China has offered economic inducements to Bhutan, while at the same time exerting military pressure through the PLA. The most blatant action was the June 2017 Doklam face-off, when the PLA started building roads near the strategic tri-junction area. India, which is treaty-bound to Bhutan's territorial integrity, had to step in. After a widely reported stand-off of over 10 weeks, both sides de-escalated the situation.

THE LATEST CHINESE CLAIMS

While there are boundary disputes in the west and the central sectors, Bhutan's eastern borders with Tibet have never drawn controversy, although China makes a claim on the Indian Arunachal Pradesh, which lies on the other side of the eastern boundary of Bhutan. This was publicly stated through Chinese maps of 2014, which at the same time showed the area west of Arunanchal Pradesh-Bhutan boundary as part of Bhutan.

In the 58th Global Environment Facility (GEF), a U.S. based environment body, meeting held on June 2, 2020, Bhutan sought funding to develop the Sakteng Wildlife Sanctuary in eastern Bhutan's Trashigang district adjoining Arunachal Pradesh. To its shock and dismay, China objected stating "in light of the Sakteng Wildlife Sanctuary in the project ID 10561 is located in the China-Bhutan disputed areas which are on the agenda of China-Bhutan boundary talk, China opposes and does not join the Council decision on this project”. Bhutan refuted the Chinese assertions with “Bhutan totally rejects the claim made by the Council Member of China. Sakteng Wildlife Sanctuary is an integral and sovereign territory of Bhutan and at no point during the boundary discussions between Bhutan and China has it featured as a disputed area”. The funding was approved by the GEF Council. Interestingly, GEF had sanctioned funding for the sanctuary earlier also, without China ever opposing.

READING THE TEA LEAVES

In the light of the ongoing Sino-Indian stand-off in eastern Ladakh, and boundary issues raised by Nepal in Kalapani, there are speculations on whether there is a larger game plan in motion which aims to corral India from all sides. This has to be seen in the perspective of rising Sino-U.S. acrimony and the aggressive moves of China in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the South China Sea. India cannot ignore the fact that the Sakteng sanctuary adjoins Arunanchal Pradesh, an area claimed by China as Southern Tibet. For China access to this area is only subject to it first seizing control of Arunanchal Pradesh as China has no land border with this area. China had never before made any claims on Bhutanese territory in this area, so why now? Similarly, China never made claims on Galwan Valley since it occupied the area in 1962, but unilaterally withdrew after the border war. Does it imply that till such time Chinese claim on Aksai Chin is accepted in toto by India, China will keep the bogey of Arunachal Pradesh alive?

On July 1, the Chinese foreign ministry issued a statement to the Hindustan Times stating that the China-Bhutan boundary has never been delimited and there “have been disputes over the eastern, central and western sections for a long time”.

A representative of the Tibetan government in exile in India, Lobsang Sangya, while speaking to CNN-News 18, claimed that they had been warning India of China’s 'five-finger strategy' for years, but in vain. According to him, when the PLA was marching into hapless Tibet, Mao had claimed that once Tibet (the palm) was occupied, the PLA would then go for the five fingers − Ladakh, Nepal, Bhutan, Sikkim, and Arunachal Pradesh. The latest Chinese gambits do little to allay these fears.

ASSESSMENT

China has perfected the art of strategic signalling, which envisages winning wars without firing a single shot. This is one in a series of messaging that they have been bombarding at a recalcitrant India to soften it and wilt to its demands. It is also aimed at scaring its allies away. Bhutan is India's staunchest supporter in South Asia, and is being used to convey to other regional countries to veer away from the ongoing Sino-Indian face-off and maintain at best, strict neutrality.

With the rest of the world unbalanced by COVID-19, and likely to remain so for some time, the Communist Party of China (CPC), at its highest level, feels confident enough that now is the time for China to robustly give voice to its territorial claims all around. Perhaps, in all this, there is a message to its only rival, the U.S. too, that this is a new-age China of ‘Wolf Warriors', one not to be trifled with in its geostrategic goals.

This dampens the hopes that the crisis in Eastern Ladakh will see an early resolution, despite the pullback agreed to after the Doval-Wang talks. Seen together with the Kalapani dispute with Nepal, China appears to be probing India's sensitive periphery, creating additional pressure points and bringing ever-increasing demands on an Indian leadership that is already under the stress of the pandemic and economic debilitation. India may be entering an era where such aggressive demands on the border will be repeatedly made.

Comments