The issue with China’s Silk Road

February 27, 2018 | Expert Insights

Australia, Japan, India, and the United States, known as the “Quad”, are reportedly in talks to develop an alternative to China’s ambitious One Belt One Road Initiative. However, critics have stated that from a development perspective, such large-scale, infrastructure-heavy projects may not achieve the results intended.

Background

China’s One Belt One Road Initiative (OBOR) was announced in 2013. Hailed as a “21st Century Silk Road”, the initiative seeks to revive trade routes across Eurasia. OBOR has been publicised as a development strategy that involves huge amounts of physical infrastructure, including railroads, highways, ports, and pipelines. According to the World Bank, OBOR has the potential to include “65 countries, 4.4 billion people, and about 40% of the global GDP”.

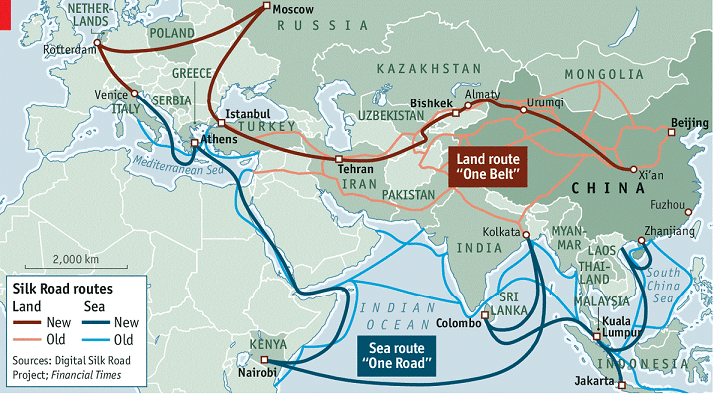

The proposed economic corridor is divided into the land-based Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB) and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road (MSR). The land route is intended to stretch from Central China through Central Asia and Russia, into Western Europe. The oceanic “road” includes ports and littoral infrastructure across South and South East Asia, the Gulf, and ends in East Africa and the Mediterranean. Most recently, China extended an invitation to South American countries to participate in this initiative.

India is one of the few South Asian countries that has not signed the deal, and remains highly sceptical of increasing Chinese influence in its neighbourhood. One of India’s main issues with OBOR is the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). CPEC not only gives China access to the Gwadar port in the Arabian Sea, but also runs partly through Pakistan occupied Kashmir. China has not yet addressed India’s concerns on this issue.

The Belt and Road initiative has become a central feature of Chinese foreign policy. It underlines China’s goal to assume a larger role in international affairs, with Beijing as the centre of a global trade network.

Analysis

Last week, media reports of an alternative to China’s OBOR emerged. India, Japan, Australia, and the United States have reportedly been in talks to establish their own global trade framework. The informal strategic dialogue between the four nations is called the “Quadrilateral Security Dialogue” or the “Quad”. The plans will reportedly be discussed when Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull visits the US for talks with President Trump. This initiative will help meet the demand for infrastructure in the continent and has been praised as a potential alternative for trade in Asia. However, critics have stated that the proposed “Quad” alternative must be called what it is: a geopolitical venture, and not an economic endeavour.

Security cooperation between the four nations has drawn Beijing’s ire. The quartet held official talks during the 2017 ASEAN Summits in Manila. India and the US have expressed concern regarding China’s growing soft power across the world, and have reportedly engaged in talks on China. Growing trade between India and Japan, and Japan and Australia’s close ties to the United States, has also drawn suspicion from Beijing.

The actual economic advantages of the projects proposed by OBOR and the Quad are limited, critics say. Agencies such as the Asia Development Bank have estimated that the region’s infrastructural needs approximate $1.5 trillion a year for more than a decade. However, Tom Holland, writing for the South China Morning Post, points out that having the capital to invest in such projects does not ensure their success. Huge regions of Asia simply lack the structural capability to draw economic benefit from such large-scale projects, he argues. The massive Chinese-funded Hambantota port in Sri Lanka, built as a part of the “21st Century Maritime Silk Road”, for example, saw dismal returns. “While physical capital like a new port or railway can be built in just a few years, building the human and institutional capital that allow that port to contribute effectively to economic and social progress is an altogether slower process…Trying to force the pace by throwing money at new projects doesn’t work. Building too much too quickly ends up destroying economic value,” he wrote.

Assessment

Our assessment is that in order to be successful, economic and infrastructural projects must consider the complexities of development. Else, projects such as OBOR remain strategies to increase global clout rather than means of development. We believe that concerns regarding China’s expanding reach are valid. In order to counter this, India must utilize its resources strategically and focus on more holistic developmental schemes. While India cannot fund and shape as grandiose a strategy as the OBOR, it can continue to build diplomatic ties and trade networks with other regional and international powers.

Read more: Alternative to OBOR

OBOR & the emerging world order

Comments