The Investment-tax Binary

June 2, 2021 | Expert Insights

Following a significant setback in the case of Cairn Energy Plc and Cairn UK Holdings Limited versus the Republic of India, the Indian government has challenged its arbitration penalty at the Hague Court of Appeal. According to the Union Finance Ministry, the $1.2 billion award is liable to be set aside, as the country had never agreed to arbitrate a national tax dispute. This development comes at a time when Cairn Energy has identified around $70 billion of overseas Indian assets for potential seizure and enforcement of the arbitral award. In fact, the company has already moved a court in the United States to sue India’s national carrier ‘Air India’ and recover part of the damages awarded to it. It remains to be seen whether the two sides can reach an amicable settlement before relevant foreign jurisdictions decide on the matter of enforcement.

THE RETROSPECTIVE DEBATE

At the heart of this arbitration dispute lies a 2012 legislative amendment to the Indian Income Tax Act, 1961, which effectively permits tax authorities to investigate transactions from 2006 for the evasion of capital gains tax. By virtue of this amendment, any transfer of shares between entities registered or incorporated outside India could be deemed taxable if the same derives value from underlying assets in the country. This retrospective provision was enacted by the Indian Parliament to reverse the effects of a Supreme Court decision in the Vodafone tax dispute. As evident from the facts of that case, the Indian government had sought to raise a demand of Rs 7,990 crore in capital gains, owing to Vodafone’s purchase of 67 per cent stake in Hutchison Whampoa. According to the taxman, Vodafone ought to have deducted the tax at source before making a payment to Hutchison, as the transaction had involved assets based in India.

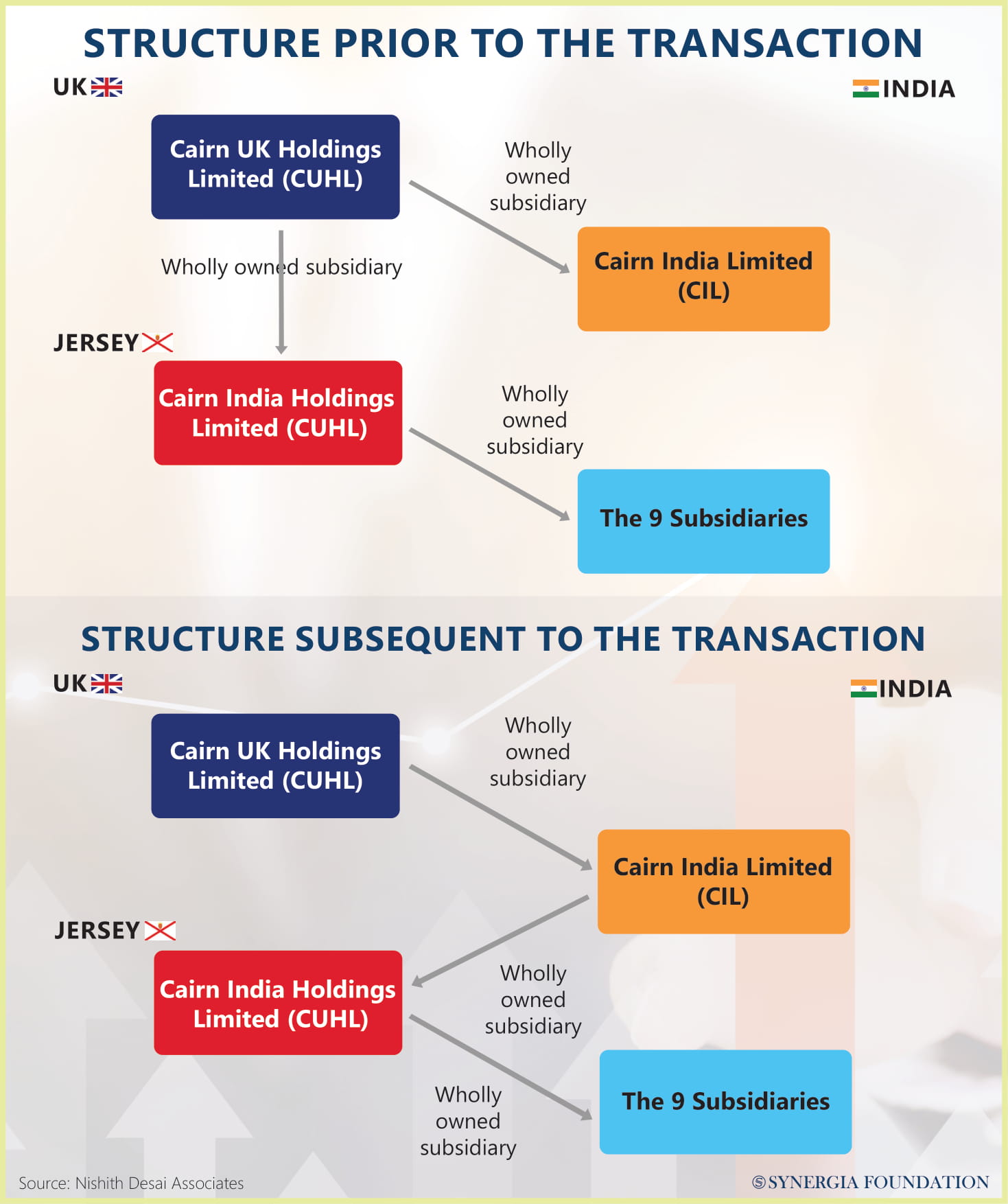

This argument, however, was categorically rejected by the Apex Court. To circumvent this judicial verdict, an amendment was brought in through the Finance Act, which conferred power on the Income Tax Department to retrospectively tax such deals. However, the retroactive application of this provision to Vodafone was deemed to be a violation of the guarantee of fair and equitable treatment, as enshrined under the India-Netherlands Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT), by an arbitration tribunal at Hague. The same amendment has now stirred controversy in the Cairn dispute. Under scrutiny is a 2006 internal restructuring of the company, through which Cairn UK Holdings Limited transferred its Indian assets to a wholly-owned subsidiary incorporated in India, namely Cairn India Limited. According to the tax authority, this transaction is subject to a capital gains tax under the 2012 retrospective amendment. Cairn, however, has argued that this levy constitutes a ‘manifest breach’ of the UK-India BIT. This position has also been upheld by the arbitration tribunal at Hague, which views the imposition of ex post facto laws as violative of international principles like ‘legal certainty’ and ‘fair and equitable treatment’. As a result, India has been ordered to pay $1.2 billion in damages, apart from other legal costs.

COMPETING INTERESTS

Implicit in the Vodafone and Cairn cases are larger questions pertaining to base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS). While countries like India argue that corporates evade taxes by transferring shares through shell corporations and complex webs of subsidiaries, others contend that these transactions amount to nothing more than prudent tax planning. In other words, there is an apparent clash between the sovereign’s right to tax and the companies’ right to use tax-saving devices. With studies suggesting that governments lose 4-10 per cent of their revenue to BEPS practices, governments around the world are keen to reform their tax structures. For example, the Biden administration has recently pushed for a global minimum corporate tax that prevents the shifting of profits to low tax jurisdictions. In altering such laws, however, the interests of foreign investors have been critically implicated. If the country that seeks to revise its tax regulations has signed an investment protection pact with the investor’s home country, then there may be sufficient grounds for alleging a breach of treaty protection. When combined with retrospective measures, as seen in the case of India, investors can potentially claim that their legitimate expectations about a stable regulatory environment were impinged upon. This is precisely the line of argument that was adopted in the Vodafone and Cairn arbitration cases. Against this backdrop, the utility of stability clauses that seek to maintain the status quo in investment protection agreements have been vigorously debated in policy circles.

ARBITRABILITY OF TAX

In investment disputes, the arbitrability of tax matters has proven to be legally contentious. Given their potential overlap with international tax treaties as well as domestic statutes of host countries, there are several questions that need to be addressed. In the absence of explicit ‘conflict avoidance’ clauses between tax treaties and investment protection agreements, it is important to determine the regime that prevails. Similarly, states must decide whether the exhaustion of local statutory remedies is essential before tax disputes are arbitrated under investment pacts. As far as India is concerned, it has unilaterally revoked its previous BITs and propounded a new model in 2015 that excludes all tax matters from investment arbitrations. Meanwhile, other states have carved out specific aspects of taxation that can be arbitrated under an international investment agreement. The language of these treaty instruments will, therefore, be key over the coming years.

ENFORCEMENT DILEMMA

Even if the first hurdle of arbitrating tax matters can be overcome, the enforcement of investment arbitral awards in India remains a sticking point. The country is not a party to the International Convention on Settlement of Investor Disputes (ICSID), which provides facilities for conciliation and arbitration of investment disputes between contracting states and nationals of other member-nations. Therefore, it is not bound to recognise and enforce the pecuniary obligations that accompany an investment award. Although India is a signatory to the New York Convention, it has availed itself of the reservation clause under Article I (3), which exempts disputes pertaining to non-commercial relationships. The domestic Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 (Arbitration Act) has further entrenched this position, raising critical questions about the enforcement of investment arbitral awards. If investment treaties are indeed deemed to be commercial in nature, then the Arbitration Act can seamlessly pave the way for enforcement. However, the Calcutta and Delhi High courts have adopted conflicting positions about the applicability of this statute to investment relationships. Unless this vital issue is resolved by a judgement of the Supreme Court, the enforceability of investment arbitral awards in India will continue to remain uncertain. Alternately, the Parliament can introduce an amendment that clarifies the scope of the Arbitration Act.

DE-ESCALATING TENSIONS

As India suffers a spate of losses in international arbitral tribunals, there are concerns that its protectionist image may hamper further investments. By declining to enforce the award, the country has joined the likes of Pakistan and Venezuela, which have faced similar actions in foreign jurisdictions against their overseas assets. Unless a robust framework is put in place for deescalating investor-state disputes, the South Asian giant’s ambitious plans to conclude free trade and investment agreements with jurisdictions like the European Union may come to nought.

Mary Kavita Dominic, is a Policy Research Associate with the Synergia Foundation. She has completed her masters in law (BCL) and South Asian Studies (MSc.) from the University of Oxford.

Comments