India’s Malnutrition Crisis

December 3, 2018 | Expert Insights

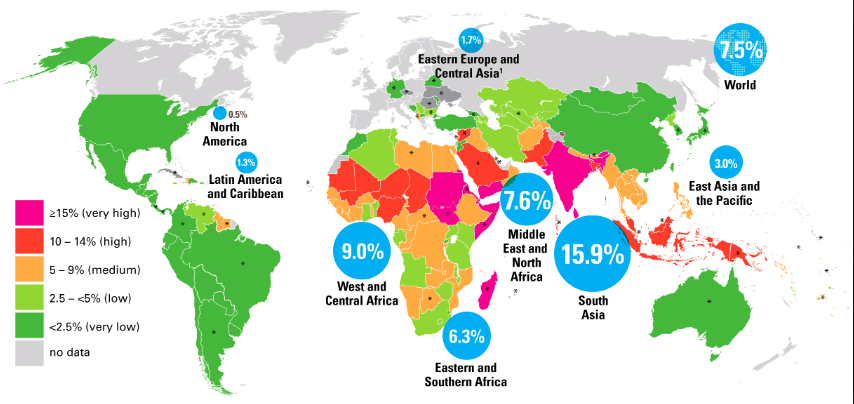

Global Nutrition Report 2018 revealed that the global burden of malnutrition is unacceptably high and now affects every country in the world. India faces a major malnutrition crisis as it holds almost a third of world's burden for stunting.

Background

The Global Nutrition Report acts as a report card on the world’s nutrition, globally, regionally, and country by country. It measures the efforts made to improve nutrition standards worldwide. The report assesses progress in meeting Global Nutrition Targets established by the World Health Assembly.

The Global Nutrition Report was conceived following the first Nutrition for Growth Initiative Summit (N4G) in 2013 as a mechanism for tracking the commitments made by 100 stakeholders spanning governments, aid donors, civil society, the UN and businesses. The following year, the first of these annual reports were published. Today, the Global Nutrition Report is the world’s leading report on the state of global nutrition. It is data-led and produced independently each year to cast a light on where progress has been made and identify where challenges remain. The report aims to inspire governments, civil society and private stakeholders to act to end malnutrition in all its forms. It also plays the important role of helping hold stakeholders to account on the commitments they have made towards tackling malnutrition. The World Health Organisation partners with the Global Nutrition Report.

Analysis

According to the 2018 Global Nutrition Report, there is a malnutrition crisis in almost every country in the world with India holding about one-third of the world's burden for stunting. Forty-six million children in India are stunted because of malnutrition and 25.5 million more are defined as "wasted" - meaning they do not weigh enough for their height. Worldwide, 150.8 million children are stunted and 50.5 million are "wasted", the report said.

Asia is one of the hardest-hit areas when it comes to malnutrition although the region experienced the largest reduction in stunting from 2000 to 2017 - from 38 percent to 23 percent. In India, high rates of malnutrition lead to anaemia, low birth rates, and delayed development, perpetuated from generation to generation. Dr. Basanta Kumar Kar - who is part of a health committee at NITI Aayog, India's government think-tank - said stunting in children is poor growth that can cause profound damage to both body and mind.

"Malnutrition is linked to mortality, morbidity, brain/cognitive development, and overall physical growth of a child. A malnourished child is vulnerable to infections and many life-threatening diseases. The odds against these children making it to secondary school, let alone managing an intellectually or physically challenging job, is slim. Malnourishment is hence also linked to productivity,” said Kar. Of the three countries that are home to almost half (47.2 percent) of all stunted children, two are in Asia: India (46.6 million) and Pakistan (10.7 million).

Researchers behind the Global Nutrition Report, which looked at 140 countries, said the problems called for a critical change in the response to this global health threat. "The uncomfortable question is not so much 'why are things so bad?' but 'why are things not better when we know so much more than before?'" said Corinna Hawkes, co-chair of the report and director of the Centre for Food Policy.

The Global Nutrition Report 2018 found while malnutrition rates are falling globally, their rate of decrease is not fast enough to meet the internationally agreed Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) to end all forms of malnutrition by 2030.

Apart from children's diets, the report flagged up gender inequality, early child-bearing, open defecation, education, and economic status as influential factors in India's malnutrition crisis. Despite available data, progress on tackling malnutrition is "simply not good enough", according to the report.

Globally none of the countries with sufficient data is on course to meet all nine targets on malnutrition. India is not set to meet any of them, the report said. Efforts have been made to ensure children are breastfed and get nutritious food in the crucial first two years of life and to improve the water they drink and sanitation in their homes.

India is the world's fastest-growing major economy and during the last two decades has recorded economic expansion that helped lift hundreds of millions out of poverty. However, it still remains a deeply stratified society with extreme inequality between its rich and poor.

Assessment

Our assessment is that in countries such as India, where there is so much emphasis on economic growth rates, apathy for malnutrition and food security is telling. We believe that such crises rob children of their futures and countries of their humanity, and feel that addressing the malnutrition problem in India should be a national priority.

Comments