Humanitarian Intervention: Can It Be Done Right?

April 30, 2022 | Expert Insights

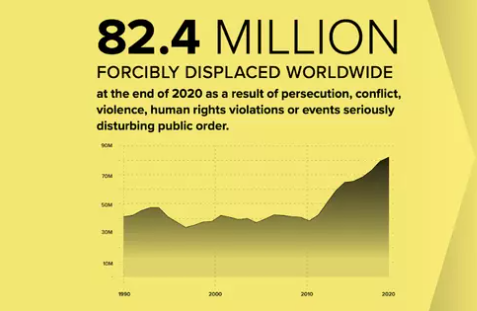

In times of conflict and bloodshed with gross violation of human rights, the normal expectation is that sooner rather than later, someone in power will step in to stop the bloodletting. However, while humanitarian intervention has the potential ability to stop violence, it comes with recognised conditions and a defined scope of responsibilities, which are not easy to undertake. Before such actions can be taken, two main questions must be answered. First, what is a humanitarian intervention? Second, when is intervention justifiable?

Background

The doctrine of humanitarian intervention has always been controversial, both in international relations and law. However, one of the fairly agreeable definitions states: "The theory of intervention on the ground of humanity (...) recognises the right of one State to exercise international control over the acts of another in regard to its internal sovereignty when contrary to the laws of humanity." The key point in this definition is the basis of humanity. This means that interveners have the responsibility to protect and not the right to intervene. In other words, interveners have an obligation to the victims and not authority over the perpetrators, which is a delicate balance to maintain. The responsibility to protect is a principle, not a norm. So, unlike basic rights, which have a legally attached definition to them, the responsibility to protect is an act of morality which has some conditions attached to it. The instances to intervene are labelled as ‘conditions of exceptionalism.’

Analysis

First, there must be a gruesome and unacknowledged violation of human rights. JS Mill, a prominent British philosopher, political economist, Member of Parliament and civil servant of the 19th century, has written, "foreigners are to accord respect to the internal politics of each state: people can only become free by their own efforts; freedom cannot be imposed on a society by outsiders."

It is true that states have the right to sovereignty and territorial integrity, and the international community must respect that. But this sovereignty also carries with it a sense of responsibility to recognise its citizens as those having their own existence and not as extensions or objects of the state. There exists a community of mankind which transcends the individual sovereign states. When states fail in their obligations to their own citizens, intervention stipulates action.

Consider the Armenian genocide, one of the unfortunate consequences of the Great War. Even speaking about the genocide in Turkey is punishable by law. Armenian President Serzh Sarkisian said, "the denial of a crime constitutes the direct continuation of that very crime. Only recognition and condemnation can prevent the repetition of such crimes in the future." One can draw a parallel between this and Russia's condemnation of speaking about the crisis in Ukraine. The biggest risk of mass violence is that it does not even recognise it as one. Under such conditions, it becomes an absolute necessity to intervene to help victims of grievous injustice.

This then brings up the next condition: victims of mass violence are unable to tackle the problem, and they do seek help. In the international community, there are instances where some states may seem to have an unfavourable structure, as seen by others. For example, the United States was determined to rid the world of communism because it did not fit into their notion of an ideal social structure. The Vietnam War is a perfect example of this. The United States initially intervened to protect the South Vietnamese, but soon their prolonged presence in the country did more harm than good. They took it upon themselves to decide what was best for the South Vietnamese, fully aware of the negative ramifications. This is certainly not a ground for intervention. Every violation of human rights does not call for intervention. In some cases, the citizens might prefer a certain form of government, or they might be able to handle the situation better because of a better local understanding. Looking at the situation in Ukraine, Ukrainians do require international assistance. However, they know their land and requirements the best. It is the responsibility of the international community to respect the sovereignty of Ukrainians and assist them as required.

History and ongoing crises have also shown the implications of non-intervention, highlighting the last condition: the ramifications of withholding intervention are worse than intervening. In his remarks to the General Assembly, Noam Chomsky described double standards as a problem of "selectivity" that produces contradictory responses characterised as "sins of omission" and "sins of commission." His problem with intervention is that it is animated more by self-interest rather than a genuine humanitarian concern.

Counter

To this, one can argue that, unfortunately, in a world of finite resources and infinite problems, there will be a degree of inconsistency. Moral principles do not exist in isolation from other principles and are challenged by practical realities. A coherent rationalist narrative would say give war a chance. Let the affected parties sort out their problems on their own, violently if needed. While this may seem insensitive and extreme, it might actually do more good than harm. Following the conditions of exceptionalism allows the international community to consider all its options and act in a timely and decisive manner. It draws a balance between upholding international peace and respecting individual sovereignty. As John Rawls, an American political and moral philosopher, says, "self-determination is an important good for people, and the foreign policy of liberal peoples should recognise that good."

Assessment

- There is no doubt about the negative implications of war and the desire to prevent it. But within the discourse of international relations and conflict, there exists a debate on when to intervene.

- Not all violations of human rights and political instability call for intervention. The instances to intervene are labelled as ‘conditions of exceptionalism.’ This helps define the scope and responsibility of the intervening party to ensure limited casualty.

- A counterview is to let the war play out without external intervention. Conflict must be allowed to end on its own terms to have lasting solutions.

Comments