Heat waves to affect South Asia : MIT

August 1, 2018 | Expert Insights

South Asia, home to one-fifth of the world population, could see humid heat rise to unsurvivable levels by the century’s end if nothing is done to halt global warming, says a study published in the journal Science advances.

Background

Climate change is a change in the statistical distribution of weather patterns when that change lasts for an extended period of time.

A historic agreement to combat climate change and unleash actions and investment towards a low carbon, resilient and sustainable future was agreed by 195 nations in Paris in 2015. The universal agreement’s main aim is to keep a global temperature rise this century well below 2 degrees Celsius and to drive efforts to limit the temperature increase even further to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

Analysis

The study warned of the summer heat waves with levels of heat and humidity that exceeds what humans can survive without protection.

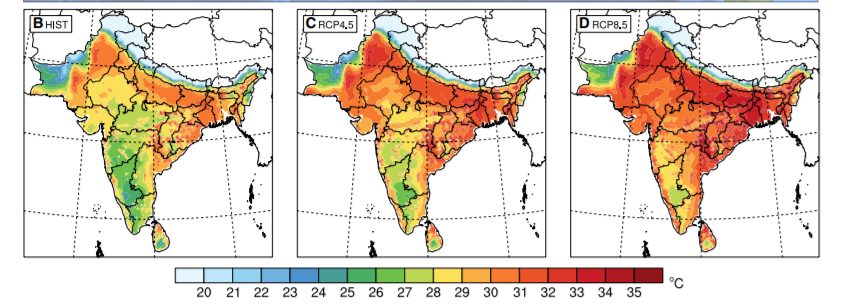

The research is based on two climate models. One is RCP 8.5, the highest scenario, commonly referred to as the business-as-usual scenario, though the IPCC itself no longer uses such a description. The other is RCP 4, which assumes moderate mitigation efforts that contain global warming to about 2.25°C over the century – slightly higher than the target to which most of the world’s nations have committed.

The scientists found that under a business-as-usual scenario, where carbon emissions are not curbed, 4% of the population would suffer unsurvivable six-hour heatwaves of 35C WBT at least once between 2071-2100. The affected cities include Lucknow in Uttar Pradesh and Patna in Bihar, each currently homes to more than two million people.

Extreme heatwaves that kill even healthy people within hours will strike parts of the Indian subcontinent unless global carbon emissions are cut sharply and soon, according to new research.

Even outside of these hotspots, three-quarters of the 1.7bn population – particularly those farming in the Ganges and Indus valleys – will be exposed to a level of humid heat classed as posing “extreme danger” towards the end of the century. The key factor issue, the authors say, is ‘wet-bulb temperature’, which is a combined measure of both ‘dry-bulb’ temperature and humidity.

Wet-bulb temperature, or TW, is defined as the temperature an air parcel would attain if cooled at constant pressure by evaporating water within it until saturation. The higher the TW, the less difference there is between human body skin temperature and the body’s core temperature, which reduces the human body’s ability to cool itself.

“Because normal human body temperature is maintained within a very narrow limit of ±1°C, disruption of the body’s ability to regulate temperature can immediately impair physical and cognitive functions,” the authors write. If the ambient air wet-bulb temperature exceeds 35°C, which is the typical human body skin temperature under warm conditions, metabolic heat can no longer be dissipated, and more than six hours’ exposure “will result in death even for the fittest of humans under shaded, well-ventilated conditions”.

The new analysis assesses the impact of climate change on the deadly combination of heat and humidity, measured as the “wet bulb” temperature (WBT). Once this reaches 35C, the human body cannot cool itself by sweating and even fit people sitting in the shade will die within six hours.

The revelations show the most severe impacts of global warming may strike those nations, such as India, whose carbon emissions are still rising as they lift millions of people out of poverty. Heatwaves are already a major risk in South Asia, with a severe episode in 2015 leading to 3,500 deaths, and India recorded its hottest ever day in 2016 when the temperature in the city of Phalodi, Rajasthan, hit 51C. Another new study this week linked the impact of climate change to the suicides of nearly 60,000 Indian farmers.

The analysis also showed that the dangerous 31C WBT level would be passed once every two years for 30% of the population – more than 500 million people – if climate change is unchecked, but for only 2% of the population if the Paris goals are met.

Counterpoint

If definite steps are taken to limit warming over the coming decades, the population exposed to harmful wet-bulb temperatures would increase from zero to just 2%. “There is a value in mitigation, as far as public health and reducing heat waves" said lead author Elfaith Eltahirhe, professor of environmental engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Assessment

Our assessment is that climate change poses an existential dilemma for countries in South Asia including India, whose greenhouse gas emissions have been increasing rapidly in recent decades because of the population and rapid economic growth.

Comments